This post has been

superseded. Further investigation showed the intriguing lead led nowhere.

The

Bibliotheca Belgica Manuscripta by

Anton Sander, a listing of Belgian manuscripts sighted in or before 1640, contains an intriguing lead at

page 215: in a codex which unites a variety of short genealogical works, there is one item described as a

Genealogia ab Adam usque ad Christum, and another described as a

Genealogia ab Adam usque ad Gedeonem. There is no note to say that these genealogies are in table form, but their owner must have had an interest in graphic stemmata, since another item in the volume is Boccaccio's

Genealogia Deorum, which often contained Boccaccio's 14th century stemmata. *

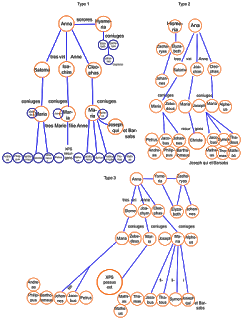

What is particularly interesting about the second genealogy (Adam-Gedeon) is that Gedeon is neither a figure in Christ's ancestry, nor, as far I know, does he figure in the bogus medieval ancestries of the European nobility. What is he doing in a genealogy? A glance at the

10th page of Plutei 20.54 in Florence suggests a

possible answer. Gedeon is the penultimate item on the fifth out of eight sheets. The Tournai codex, which seems to be a grab-bag of thieved and salvaged fragments,

might have contained an incomplete

Epsilon manuscript where the last three sheets that cover the period from David to Christ had been lost.

After 370 years, this codex probably no longer exists. Sander saw it in Tournai Cathedral Library.** It had been left to the library by Denis de Villers, who seems to have been chancellor of the diocese (I'm not fully clear about the ecclesiastical offices in this period).*** Tournai and its cultural treasures were bombed by the Luftwaffe in 1940, and much was lost (

pictures).

How do we discover the fate of the genealogy codex? The Bibliothecae Cathedralis Ecclesiae Tornacensis now has a

weblink, but this codex is not listed. I searched for "Genealogia ab Adam..." and a selection of the other partworks in

In Principio, the Brepols database of incipits, but found no promising leads. Where else should I look? Has anybody analysed Sander's work and established, codex by codex, what happened to the various manuscripts?

* Sander's book was published by Insulis, Ex officina Tussani le Clercq, apparently a printer at

Lille in France.

** Sander describes the legacy thus: codices Mss. qui sunt in bibliotheca reverendi Domini Hieronymi de Winghe canonici Tornacensis, nunc in bibliotheca publica eccelsiae cathedralis solerte studio et cura R.D. Ioannis Baptistae Stratii decani et donationibus clarissimorum viriorum Hieronymi Winghii, Dionysii Villerii, ac Claudii Dausqueii, eiusdem ecclesiae canonicorum inchoata et luculenta editorum voluminum supellectile instructa.

*** Samaran, Ch. 'La Chronique latine inédite', says Denis de Villers (1546-1620) was a literary man of Tournai, versed in genealogy and numismatics, who held a doctorate in canon law from Louvain University. He and canon Jerome van Winghe founded the cathedral library which is now the Tournai public library (

catalog) (article in

Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes (1926), 87,144,

note 3). There is a more substantial 2004 article by Claude Sorgeloos on de Villers' book collecting

here and note 9 says most of de Villers' books were destroyed in the bombardment in 1940. However some had been moved to

Mons (

catalog) and

Courtrai (

catalog) and were saved, and one of de Villers' books from Tournai later ended up in the hands of Sir Thomas Phillipps, so perhaps we should also check records of the Phillipps

auctions.