How did we get here?

In early 2014, the years of dismal efforts at the Vatican to create an online manuscripts portal had nothing much to show. The DigiVatLib site at that time was a hand me down. It indexed a few hundred manuscripts which had in fact been scanned for Germany's Bibliotheca Palatina Project, mainly funded by the Manfred Lautenschläger Stiftung, and copied to Rome for free.

The site only offered 24 items from the Vatican Library's other collections. Bear in mind that this was the world's biggest manuscript library, with more than 82,000 handwritten books in the vaults.

On March 20, 2014, a news conference announced a new contractor for digitization, NTT Data, a Japanese software company. It was an historic decision, because this professionalized a project that had been dogged by incompetence, and made it more attractive to wealthy donors who expected to see results for their money. NTT Data Italia did even more. It put up seed money, tossing in a whopping 18 million euros of its own, nominally to digitize 3,000 named manuscripts up to 2019.

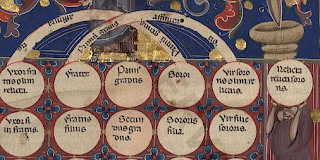

Experts could thus be hired and servers bought. The fact that the tally of digitizations on the site's front page is now 15,000 presumably means that other funding has been added to the mix, although the Vatican Library does not publish income data. We do know that the Polonsky Project came in with about 1 million euros to digitize Hebrew and Greek manuscripts at the Vatican, work that ended last month. Mellon pitched in 563,000 dollars this year, but for metadata, not digitization.

The pace has kept accelerating. In May 2015, the manuscripts portal managed to surpass 2,000 items, and on November 3, 2015, it breached the 3,000 barrier, making it the biggest digitization program in Italy, overtaking the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence. During 2016, the portal doubled in size.

In January of this year, the program ballooned from 6,000 to 10,338 items overnight by an expedient. Much of the manuscript collection is backed up by old-fashioned black-and-white microfilm and some of these films had been scanned at client request, so these digital scans were placed online. These low-resolution images are a stopgap while high-resolution color scans of the same codices are being carried out.

The fact that we are now at the 15,000 mark indicates the project is not only in the finest of health, but also scores as probably the biggest manuscript portal in the world, though firm comparative data is hard to come by.

A search of the French national site Gallica for "manuscripts" with dates before 1600 produces 20,475 hits, but a significant number of these are single-page items. In Spain, the Biblioteca Digital Hispánica shows 15,971 manuscripts online, but the number sinks to 10,716 if you filter out post-1600 dates. Munich's Digitale Sammlungen shows about 5,300 digitized manuscripts earlier than 1600, whereas Manuscripta Mediaevalia, a portal which consolidates many of the German and Swiss repositories (including Munich, but not other centers), shows 13,340 digitized "manuscripts" online, but only 5,954 dating before 1600. Italy's Internet Culturale claims 19,426 online pre-1600 manuscripts at Italian libraries (not the Vatican), but this is full of duplicates. Of the total, 18,284 hits represent just 3,000 codices at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence.

To summarize, and this is only an informed hunch, the current size of the four biggest national virtual libraries, counting just codices (multipage books) from before 1600 only, may be:

| Vatican: | 12,000 |

| France: | 11,000 |

| Spain: | 11,000 |

| Germany: | 6,000 |

What remains to be improved? My first beef with the portal is its slowness to download. The biggest single collection, Vat.lat., now offers nearly 4,000 manuscripts with 4,000 fiddly little thumbnail pictures coming down the pipe at you in one unwieldy page. There is no URL leading to a text-only main-site index of Vat.lat. Please, DigiVatLib, break up the Vat.Lib. table of contents into several sub-collections: 1-999, 1000-1999, and so on.

A second desideratum is to digitize the hand-written catalogs from the Vatican Library's Sala Consultatione MSS. These hand lists are not only vital as finding aids to the collections. They would provide provisional descriptions for the many manuscripts that go online with no metadata whatever. And these hand-annotated books are historic documents of world rank in their own right. As long as these are withheld from virtual users of the library, there can be no pretence that use of the portal is as good as going to Rome in person.