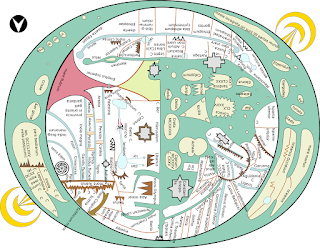

It may rate as the grandest facsimile atlas of all time: the Monumenta Cartographica Africae et Egyptiae of Prince Youssouf Kamal of Egypt. Sixteen volumes of reproductions of old maps and texts concerned with historical geography, in a limited edition of 100 deposited in the great libraries.

There's some good news. A few weeks ago, the National Library of Spain's digitization program scanned three of its fascicles as the bound volumes are designated. You can now turn some of the pages of this fascinating book from home, a privilege previously only open to the royalty who got suchlike as gifts, or billionaires who could bribe their way to interloan it :-).

The links are below. Why the BNE is omitting parts of the series (perhaps it does not own them?) is unclear. I introduced Prince Kamal's unique research and publishing project in a post in May where his motivations are considered. Certainly nothing of its kind will ever be attempted in print again, since today digital is far easier.

The 16 fascicles by number, highlights indicate the three online:

The 16 fascicles by number, highlights indicate the three online:

1 ; Époque avant Ptolémée (pp 1-107)

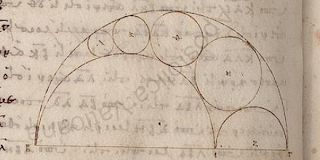

2,1 ; Ptolémée et époque Gréco-Romano

2,2 ; Ptolémée et époque Gréco-Romano

2,3 ; Ptolémée et époque Gréco-Romano (pp 362-480)

2,4 ; Atlas antiquus et index

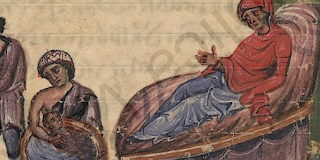

3,1 ; Époque arabe (pp 482-583)

3,2 ; Époque arabe

3,3 ; Époque arabe

3,4 ; Époque arabe

3,5 : Title? pp 946-1072

4,1 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

4,2 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

4,3 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

4,4 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

5,1 ; Additamenta : Naissance et évolution de la cartographie moderne

5,2 ; Additamenta : Naissance et évolution de la cartographie moderne

2,1 ; Ptolémée et époque Gréco-Romano

2,2 ; Ptolémée et époque Gréco-Romano

2,3 ; Ptolémée et époque Gréco-Romano (pp 362-480)

2,4 ; Atlas antiquus et index

3,1 ; Époque arabe (pp 482-583)

3,2 ; Époque arabe

3,3 ; Époque arabe

3,4 ; Époque arabe

3,5 : Title? pp 946-1072

4,1 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

4,2 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

4,3 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

4,4 ; Époque des portulans, suivie par l'époque des découvertes

5,1 ; Additamenta : Naissance et évolution de la cartographie moderne

5,2 ; Additamenta : Naissance et évolution de la cartographie moderne