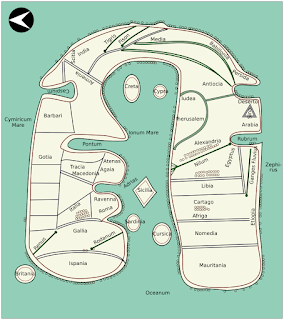

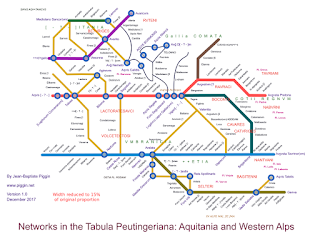

My analysis of the Tabula Peutingeriana's western end has yielded a big surprise. To see what this is about, take a glance at how the manuscript depicts the area we associate with modern France (below):

It's strangely formless. Definitely not a hexagon. The Atlantic coast at left seems to have gone mostly missing. The outline looks vaguely like a sperm whale. What's that strange mouth or slit in the left-hand edge? Scholars have always been astonished at the crudeness of this late-antique "map". So I wasn't expecting to find any graphic intricacy here.

But there is something clever going on, and the first clue is that slit, which is marked

Sinus Aquitanicus, the Bay of Aquitaine or as would today say, of Biscay. All seas and gulfs in the Tabula Peutingeriana (TP) are compressed into river shapes, so it is in itself unremarkable that the Bay of Biscay is not being shown here as the wide bight we are familiar with from modern maps.

The area below the slit was evidently marked Aquitania in the original TP, though some letters are now missing.

What is peculiar is the way the slit separates places which we would conventionally expect to abut one another on the plains of western France. At the deepest point of the slit is the inland city of

Lemuno (Poitiers), on its top flank are

Dartoritum (Vannes) and

Portu Namnetum (Nantes) and on its bottom flank are

Audonnaco (Aulnay) and

Mediolano Sancorum (Saintes), all inland.

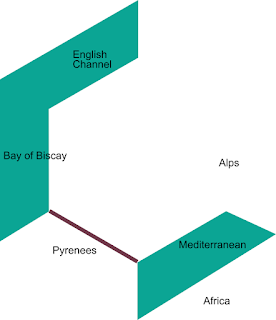

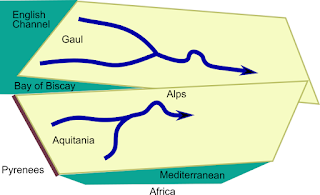

To grasp how this odd watery border has arisen, the best tool of thought is the hexagon, a meme which normally denotes the political frontiers of modern France, but which I will apply to the natural limits, mountainous and marine, of Roman-era Aquitania and transmontane Gaul as far as the left bank of the Rhine:

My method for analysing pre-medieval charts is based on the observation that there are graphic continuities and discontinuities in every large diagram. These become obscured during cumulative copying by scribes. The TP's principal

continuities are its long-distance routes, probably based on recorded itineraries. As a matter of prudence, I now denote these as "courses", since it cannot be proven that the TP itself was ever intended to guide travel.

In the present state of the TP - preserved as it is in a single manuscript from late in the long 12th century - some of these courses have become obscured by crowding, but can be recovered by careful examination. Where a long horizontal series of chicanes - the vernacular of the diagram - matches a direct-line, real-world journeying route, we are likely to have found such a course.

As far as I know, scholars have previously failed to notice that in Aquitania, correspond to roads running from southwest to northeast into the Alps, whereas in Gaul and the rest of the West, the TP privileges a set of courses that align with roads running northwest-southeast. Below, I have added a couple of pale yellow parallelograms to the hexagon to show these contrary orientations:

These continuities lead us in turn to discern a

discontinuity. There is a break between these two sets of courses. Part of that break is formed by the Sinus Aquitanicus slit, and the rest of the break spreads to the right: a zone of transition where the courses of the two types are tangled or contorted or there are unaccountable blanks. I will develop these observations in detail further on.

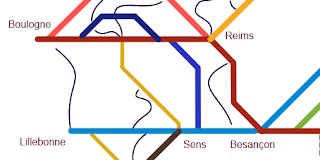

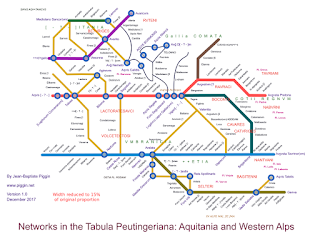

The most plausible explanation for such a discontinuity would be that the TP was constructed from two separate data-sets, or perhaps even from two pre-existing charts. I have recently analysed the southernmost of these two datasets, the region abutting the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean, and established that it emphasizes seven main routes which vary in length, are more or less parallel and are connected to one another by shorter minor routes. The following transport-system diagram is the result of this analysis:

You can see here two main horizontal courses (red and blue) flanked by the dark green, purple, chocolate, chartreuse and olive green courses (five in all) that are semi-parallel to them. The 15 yellow courses are transverse connections. It is surprising that a journey which modern travellers would regard as a trunk route, the Rhone valley highway from Arles to Valence to Vienne, is treated here as a minor link. The six thin curved lines represent connections near Lyon that do not fit this context. That is because they belong to the transition zone.

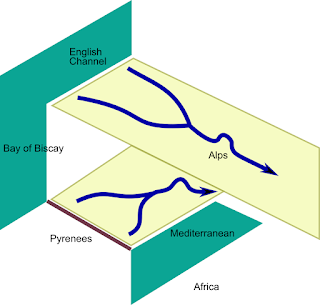

I have not yet completed a similar analysis for northern Gaul, but can say already that that part of the TP emphasizes a set of courses running from Normandy and the English Channel across to the main Alpine crossings..

Armed with this knowledge, we can estimate with greater confidence how the TP was put together. To merge the two datasets, the sub-maps had to be rotated so that all the courses were depicted more or less in parallel. The Bay of Biscay was changed from a full side of the hexagon to a mere slit between the two sections, and the Mediterranean Sea was squeezed down to a kind of river:

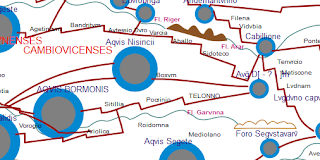

Let's finish with a look at the zone of transition, depicted in my abstract above by thin black curving lines. The labels are more legible in my plot than in the manuscript, so let's use that for the discussion.

The road southwards from

Cabillione (Chalon) to

Lugduno (Lyon) is depicted as a vertical ladder, a rather exceptional graphic form for this chart.

Augustodunum (Autun) which is at a more northerly latitude than Chalon is nevertheless shown directly

below it. The principal paved Roman crossing of the Morvan uplands is that from Autun to

Autessioduro (Auxerre), whereas the connections from Autun to

Degetia (Decize) - just peeping above from the left margin - are of less importance.

Here there appear to be no fewer than three courses: via

Aquae Nisincii (

Saint-Honoré-les-Bains?); via

Boxum (

Bussière?); and via

Aquae Bormonis (Bourbon-Lancy). (For an up-to-date discussion of these identifications and their past as sacred Celtic sites, see Nouvel (2012) and Hofeneder (2011).)

If we consult this 75-kilometre-wide space on an online map, it's noticeable that these three courses relate to a tiny geographical area, with a radius of a single day's walk. Yet the area is being given unusually detailed treatment in the TP. Its paths are circuitous, poorly aligned with the major east-west courses to the north and south and too local for long-distance travel. The chart's graphic arrangement of the small towns and spas does not even represent their real-world spatial organization very well.

I have suggested in the case of Italy that such passages in the TP are most likely to be write-ins on the chart where general consistency was no longer achievable and insufficient blank space was available to make the additions coherent. It is for this reason that I exclude them for the time being from the main analysis and treat them as if they were glosses.

My working hypothesis is that not all lines on the TP are alike: some

are primary courses, offering chains of straight-line distances that

stretch across regions, others are secondary or local courses, showing

cross-connections between the primary courses, and others again are

infillings or graphic annotations added after the chart was completed.

The zone between Decize, Chalon and Lyon may have been left blank in the earliest version of the TP, extending inland the watery blank formed by the TP's

Sinus Aquitanicus

Hofeneder, Andreas. ‘Tabula Peutingeriana’. In Die Religion der Kelten in den antiken literarischen Zeugnissen 3, Vol. 75. Mitteilungen der Prähistorischen Kommission. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2011.

Nouvel, Pierre. ‘

Les voies romaines en Bourgogne antique: le cas de la voie dite de l’Océan attribuée à Agrippa’. In

Voies de communications des temps gallo-romains au XXème siècle, edited by C Corbin, 9–57. Saulieu, France, 2012.