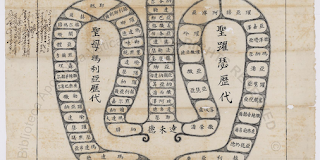

Just after 1700 CE, Chinese experts accepted an extraordinary commission: to devise a poster-sized infographic to depict the ancestry of Jesus Christ. Their help had been sought by Carlo Orazio da Castorano (1673-1755), a Franciscan missionary in Shandong, a city 400 kilometres south of Beijing.

The only known copy of the poster that the unknown Shandong designer/engraver and printer (perhaps assisted by an editor) produced is now in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana in Rome.

This fusion of Latin late antique ideas and creative Qing-period design has a special place in world cognitive history. The poster is about 125 centimetres high. Several weeks ago, the Digita Vaticana, the digitization programme at the BAV in Rome, brought

Vat.estr.or.55 online, as I

noted at the time.

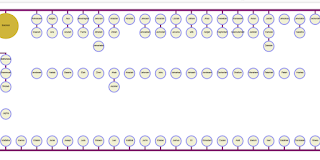

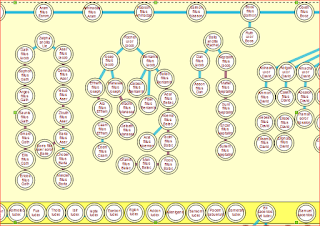

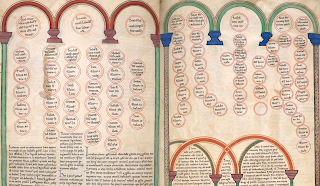

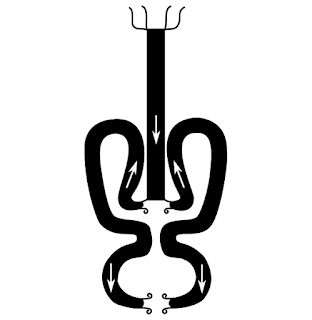

The poster published in 1704 shows a dual genealogy of Jesus, beginning as a single stream at Adam at top, dividing at David into the line of Nathan at left and the line of Solomon at right. The left loops comprise a genealogy according to the

Gospel of Luke, and the right loops that in the

Gospel of Matthew. The overall shape ends up looking something like a guitar. Jesus occupies the gap at the base. Here is a schematic summary of it. The white arrows show the direction of descent:

What the diagram achieves in cognitive terms is this: It visualizes the

genealogy of Jesus as a combination of flow-chart and network. What

began as mythic stories and oral history among Jews is here translated

from the linguistic sphere of knowledge into the visual-spatial sphere,

where the reader is invited to comprehend it with a different cognitive

system of the mind. In addition, the chart re-imagines all this in a Chinese cultural mode.

Orazio, whose Italian surname is also spelled as Orazi and whose Chinese name was 康和子 (Kāng Hézi), was just 31 and had barely been four years in China when the Qing artists or craftsmen accepted his briefing to make this extraordinary graphic. (I rely on Michela Catto's

account of him in the Dictionary of Italian National Biography, and also notes by

Michael Mungello.)

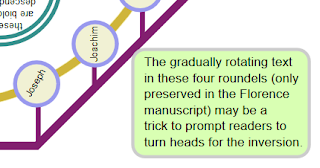

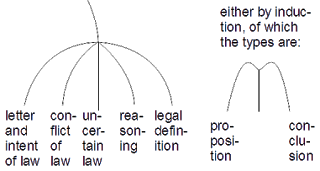

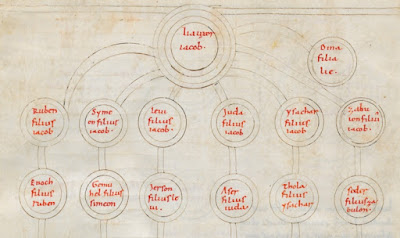

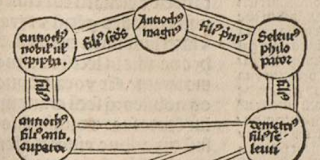

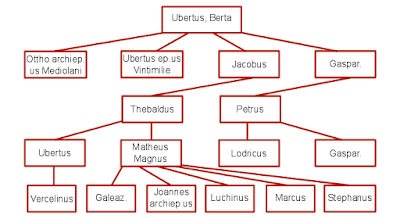

Although only Kāng Hézi and none of the other creative contributors is named on the poster, a modicum of post-colonial common sense suggests that while the basic idea was the young Orazio's, the execution, probably by directly engraving a metal plate, required much Chinese artistic and technical talent. Where Orazio would have requested European-style roundels and connectors like this ...

... the designer/engraver must have persuaded him to instead accept cells, oval in shape, fitted together in a broad band:

The cells make eminent sense in a Chinese context. Their shape makes them recognizable as analogues of ancestral tablets. Their organization into paths might have seemed a little strange to a Chinese readership. The paths make the chart akin to a map. The diagram is termed a "tú" (圖) or chart, with the full title

Wúzhǔ Yēsū jí tiānxià wànmín lìdài zōngpài tú (吾主耶穌及天下萬民歷代宗派圖) (Dudink).

The advantage for Orazio and his partners in setting the cells flush was

that this ensured enough space for the names to be legible, while not

making the poster any bigger than the largest commercially available

paper sheets for printing in China. The compression of the main lines of ancestry

into such a circuitous shape assists the illusion of equality between

the lines of

Luke (left) and

Matthew (right). These

aspects too may have been the engraver/designer's own idea, not

Orazio's. Considerable effort has also been applied to softening the

lines by composing them of tiny brushwork and by feathering all the line

ends.

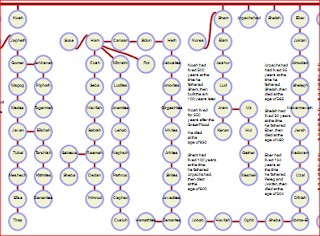

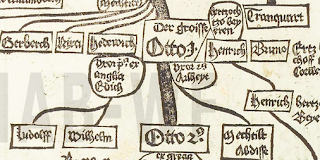

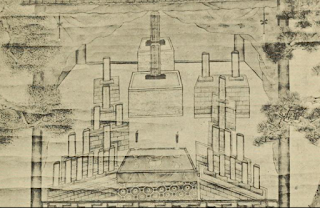

It is interesting to compare this diagram with an ancestral scroll of uncertain date

collected in Shandong only 200 years after the Orazio diagram was made (quoted by Cohen from Johnston). This visualizes family as tablets arranged in a top-down stemmatic fashion, suggesting the Orazio diagram would have been readily cognizable for a northern Chinese audience as a genealogy:

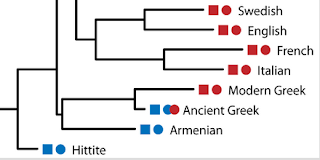

Both China and the West had long histories of experiments with visualizing abstract information of hierarchical form for genealogy. A type of stemmatic chart known as a sū shì zōng tú pǔ (蘇氏宗圖譜) was invented in the Northern Song (960-1279) state while another style known as a bǎo tǎ shì tú pǔ (寶塔式圖譜) was popular in the Southern Song state (Chao).

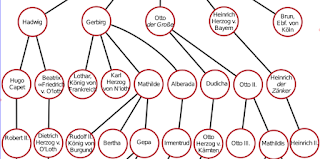

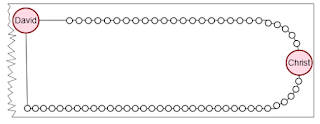

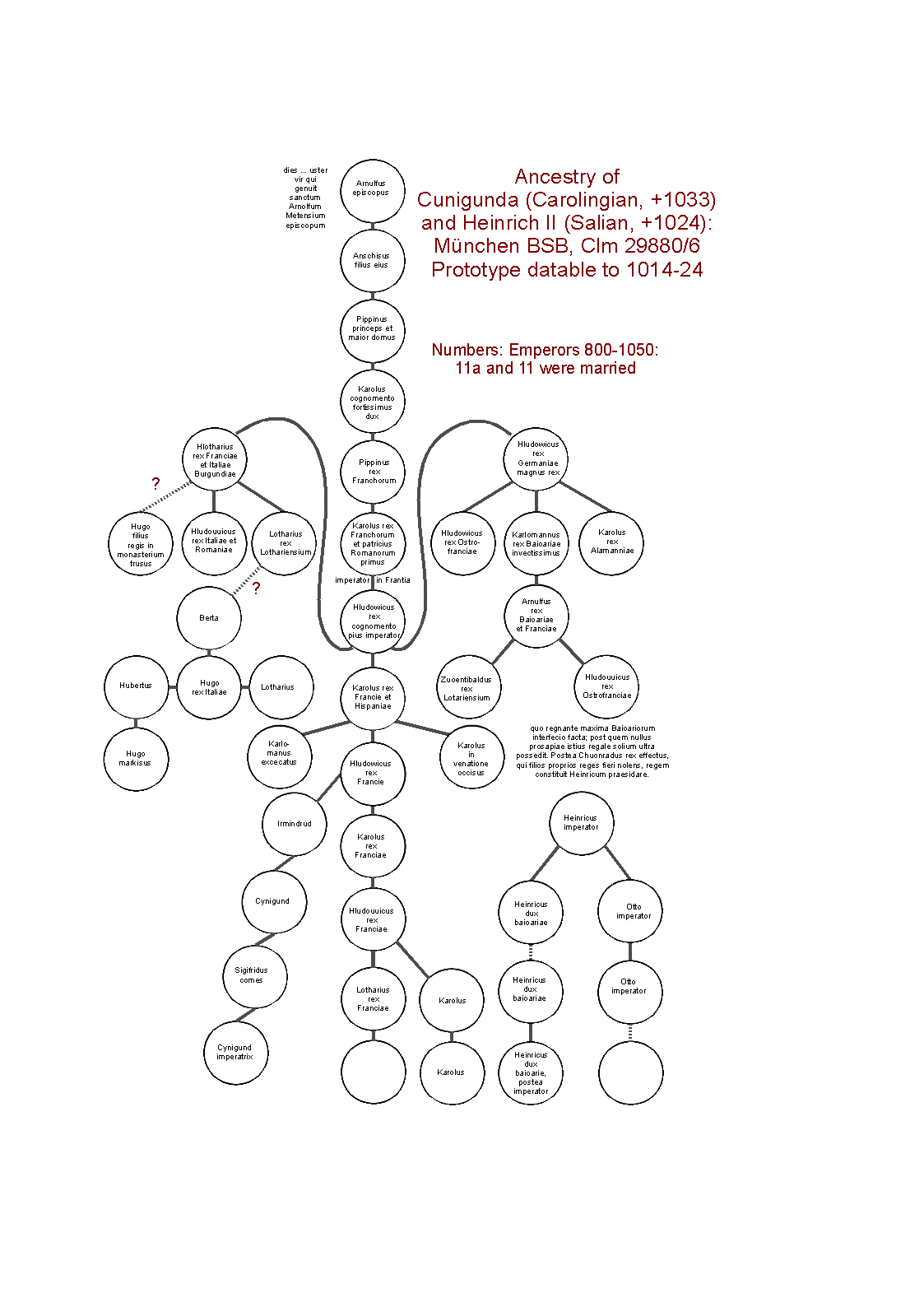

Europe's experiments with similar graphic layouts go back somewhat further. My own research has established the date of the oldest extant graphic genealogy as before 427 CE. Like the Tú, the Great Stemma also sets out a genealogy of Christ. You see a

reconstruction of it on my website along with a link to the main

publication about it.

The Orazio chart is likely to have been the first occasion when these separate traditions fused into a single creative work at the highest level of expertise.

Orazio may or may not have learned during his Franciscan formation in Teramo, Italy of the late antique Great Stemma. The Franciscans were a conservative order theologically, less intellectually adventurous than the Jesuits, but with a long-standing interest in graphics as a means to evangelize, so Orazio may well have remembered and kept an abiding impression in his mind of old posters and charts, even one based on work from 1,300 years earlier.

The central idea around which the Great Stemma is based is to show the

Luke and

Matthew genealogies as streams separating after David and then rejoining at Jesus, as follows:

The idea of presenting the two genealogies as streams or

fila

that part and then reunite at Christ is something so distinct, so

inspired, and even so idiosyncratic that it is hard to avoid the

impression that there is some kind of hidden chain of influence leading from the Great Stemma

to the Tú.

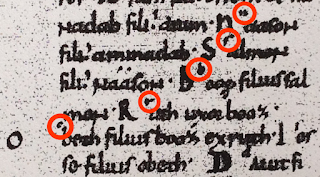

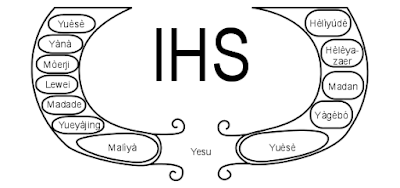

I have no knowledge of Chinese, so with the help of an excellent

student of medicine and Chinese, Lennard Piggin, I transliterated the confluence section of the chart to pinyin so I could read it. I have not entered all the tone marks, as they are difficult to type, but you will get the idea:

This yielded something else that surprised me. The majority Catholic view of the two gospels holds that both

Matthew and

Luke set out an ancestry of Joseph (phoneticized Yuèsè in Chinese).

But here, both genealogies terminate at Yēsū (Jesus) and the name to the left of Jesus is Malíyá (Maria) and to the left of that is Yueyàjing (Joachim). Neither of the latter names is given in

Luke 3:23.

The insertion of both names as a bridge can be traced back to an apocryphal second-century work, the

Protevangelion of James. Along with the two gospels, the

Protevangelion is the hidden, third documentary source on which the chart ultimately relies for its information. To find out more about the apocryphal figure of Joachim, read my

Joachim article.

In this case too, the similarity of conception leading from the Great Stemma

to the Tú is startling. The anonymous Great Stemma's main motivation appears to have been to propound the Joachimite theory. It was modified in later use to bring the chart into line with the orthodox Christian position.

But in the Tú, the Joachimite theory is revived. Dudink argues that there is an intermediate influence at work here: the writings of the forger Gianni Nanni (1432-1502), better

known as Annius of Viterbo. Orazio altered the Lucan names "Eli" and "Joseph", changing them to "Joachim" and "Maria" respectively, relying on a bogus claim by Annius to have "discovered" an ancient error in

Luke.

There is a third similarity between the Great Stemma and the Tú. In the text section of the Tú, Orazio set out an age-of-the-world chronology drawn from the

Chronological Canons of Eusebius of Caesarea, and thus from the Septuagint and Vetus Latina version of the Old Testament, not from the Masoretic and Vulgate version which was authoritative for Catholics in 1704.

The Great Stemma is similarly based on a Vetus Latina chronology. There is however a key difference between it and the Tú: the Great Stemma omits a patriarch known as the Second Cainan or Kenan, whereas the Tú includes Cainan II (嘉宜南). You can find a full list of the names used in the Great Stemma on my

Luke page. The names in the Tú have been published in full by Dudink.

The three resemblances are very striking, but I think on reflection that it is unlikely that Orazio ever actually saw the Great Stemma, let alone consciously reproduced it in a Chinese version.

What Orazio took to China is more likely to have been an undefined mental "picture" of the Jesus genealogy picked up during his formation with the help of some kind of visual teaching materials.

He must have explained to his partners in Shandong what he had seen in Italy and how he envisaged recreating this in China. During their collaboration, almost everything for the chart had to be created again from scratch. Not even a phoneticization of the biblical names into Mandarin forms existed yet. All the conversions had to be devised by Orazio and his Chinese scholarly partners. In many cases they are unique, and were

not adopted by later translations of the Christian Bible to Chinese.

The chart, when finally published was therefore a vast and complex creative effort mingling advanced epistemological and communications ideas from east and west. I have very little knowledge of stemmatic graphics in China and will leave it to others to draw conclusions about that, but this story of fusion does reveal something interesting about the western side of the interaction.

There is only one copy of the Great Stemma in unadulterated form left in Italy,

Florence plut. 20.54. Two others

seem to have existed, but have vanished. I do not know of any post-Renaissance graphics directly based on the Great Stemma. It does however seem that despite the paucity of graphic evidence, elements of the tradition of the Great Stemma remained alive among the 17th-century Franciscan teachers who formed Orazio in the Papal States.

The idea of teaching the ancestry of Jesus by visualizing it rather than just talking about it does seem to have persisted, even though the tradition of copying the Great Stemma had by then ceased and most of the extant copies of this late antique masterwork had vanished. That China, not the West, put to paper the last trace of the tradition is one of the more remarkable paradoxes of history.

Cams, Mario. ‘Not Just a Jesuit Atlas of China: Qing Imperial Cartography and Its European Connections’. Imago Mundi 69, no. 2 (3 July 2017): 188–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085694.2017.1312114.

Chao, Sheau-yueh J. “Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans.” Journal of East Asian Libraries 129, no. 1 (2003): 23–40.

Cohen, Myron L. “Lineage Organization in North China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 49, no. 03 (1990): 509–34.

Dudink, Ad. “Biblical Chronology and the Transmission of the Theory of Six ‘World Ages’ to China: Gezhi aolüe...(Outline of the Mystery [revealed Through] Natural Science; before 1723).”

East Asian Science, Technology & Medicine 35 (2012): 89–138 (

Online: paywall).

Johnston, Reginald F.

Lion and Dragon in Northern China. New York: Dutton, 1910.

Archive.org.