In the 500 years since the rediscovery of the only extant Roman chart of the world, no one has proved how it was made. I am treating that as a challenge.

There is now progress towards a solution to report. My working method is to revisualize the manuscript, the Tabula Peutingeriana, by laying its route network over a modern map of the world. This is impossible to do with the whole TP chart, but surprisingly this works quite well with some more localized regions.

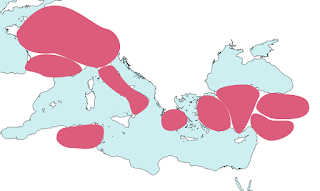

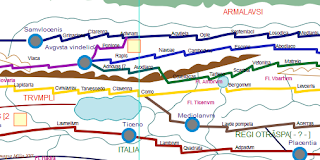

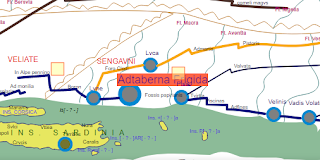

If one increases the page height of the route network, one often finds a sweet spot where the layout of a whole swatch of cities fairly closely matches their pattern on a modern map. This correspondence between overlay and underlay rarely extends beyond discrete geographical areas, for example Greece or the Italian peninsula. After surveying about 60 per cent of the Tabula, I have so far found nine of these patches. This diagram of their locations around the Mediterranean Basin shows them:

At the time when I was discovering the first three or four by trial and error (previous post), I was still sceptical. I did not even bother to note the patches' exact angles of divergence from a north orientation, and I still remained concerned that the patches might later turn out to be nothing more than a chance alignment in the data.

But by the time I moved to analysing Anatolia it was clear that alignment was a rule that was a reliable predictor of where towns were going to be found on the TP.

These patches are in some way comparable to the wireless cells of a cellular phone system extending over a landscape. Unlike a territory, the edges of the cells are not distinct, and there are some places that are outside any cell. But within each cell, an objectively measurable value prevails uniformly.

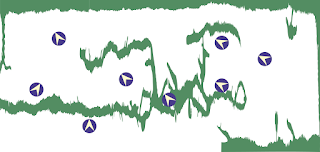

The phenomenon can alternatively be visualized by showing bearings on a horizontally compressed copy of the Tabula Peutingeriana. In the following sketch, you can see how Provence (the leftmost region) is drawn with north at the upper right, whereas Gallia Comata (top left) has north at the upper left:

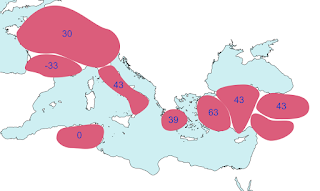

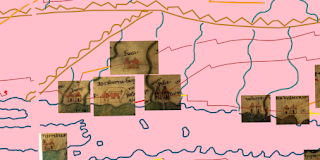

The cells are distinguished from their neighbours by an objectively measurable value: an angle of difference between lines of longitude (I have the latitude/longitude data for these places) and verticality between places on the TP (I have a database of the coordinates), as shown below.

We could attach a mathematical value to every place-label on the chart, group these and analyse them statistically to find more patterns.

This is still a work in progress, and I can only speculate about where this is leading to. But I have a suspicion. The maker of the Tabula Peutingeriana may have designed his diagram with the help of a collection of "chorographic" charts which depicted different regions with varying orientations.

A majority of scholars nowadays think that the world of antiquity had little familiarity with scale maps (despite Ptolemy of Alexandria having written a book, still extant, on how to make a map of the world). A cruder type of chart, the pinax chôrographikos, was adequate to explain locations visually, and even this visualization may not have come into use among educated people until late antiquity.

The only instances of an ancient Greek/Latin pinax chôrographikos we know at present are the mappaemundi (see my previous post), the controversial sketch on the "Artemidorus Papyrus" and the Dura Europos "shield". Each of these seems to have a different compass direction at top and it may be that a varying, ad hoc orientation is the hallmark of the pinax chôrographikos.

If this hypothesis turns out to be correct, it may be that we will be able reconstruct several more pinakes using the data in the Tabula Peutingeriana, which would mark a major advance in the study of early cartography.

You can see the graphic abstracts for eight of the TP cells on my website, as listed below. On each chart, press the "landmass-on" button to see how the layout compares to the geographical situation.

Each of these revisualizations may give at least the layout of what might have been drawn on an early pinax.

The more immediate object of this research is however to focus on the creation of the TP, which might have taken place as follows:

There is now progress towards a solution to report. My working method is to revisualize the manuscript, the Tabula Peutingeriana, by laying its route network over a modern map of the world. This is impossible to do with the whole TP chart, but surprisingly this works quite well with some more localized regions.

If one increases the page height of the route network, one often finds a sweet spot where the layout of a whole swatch of cities fairly closely matches their pattern on a modern map. This correspondence between overlay and underlay rarely extends beyond discrete geographical areas, for example Greece or the Italian peninsula. After surveying about 60 per cent of the Tabula, I have so far found nine of these patches. This diagram of their locations around the Mediterranean Basin shows them:

At the time when I was discovering the first three or four by trial and error (previous post), I was still sceptical. I did not even bother to note the patches' exact angles of divergence from a north orientation, and I still remained concerned that the patches might later turn out to be nothing more than a chance alignment in the data.

But by the time I moved to analysing Anatolia it was clear that alignment was a rule that was a reliable predictor of where towns were going to be found on the TP.

These patches are in some way comparable to the wireless cells of a cellular phone system extending over a landscape. Unlike a territory, the edges of the cells are not distinct, and there are some places that are outside any cell. But within each cell, an objectively measurable value prevails uniformly.

The phenomenon can alternatively be visualized by showing bearings on a horizontally compressed copy of the Tabula Peutingeriana. In the following sketch, you can see how Provence (the leftmost region) is drawn with north at the upper right, whereas Gallia Comata (top left) has north at the upper left:

The cells are distinguished from their neighbours by an objectively measurable value: an angle of difference between lines of longitude (I have the latitude/longitude data for these places) and verticality between places on the TP (I have a database of the coordinates), as shown below.

We could attach a mathematical value to every place-label on the chart, group these and analyse them statistically to find more patterns.

This is still a work in progress, and I can only speculate about where this is leading to. But I have a suspicion. The maker of the Tabula Peutingeriana may have designed his diagram with the help of a collection of "chorographic" charts which depicted different regions with varying orientations.

A majority of scholars nowadays think that the world of antiquity had little familiarity with scale maps (despite Ptolemy of Alexandria having written a book, still extant, on how to make a map of the world). A cruder type of chart, the pinax chôrographikos, was adequate to explain locations visually, and even this visualization may not have come into use among educated people until late antiquity.

The only instances of an ancient Greek/Latin pinax chôrographikos we know at present are the mappaemundi (see my previous post), the controversial sketch on the "Artemidorus Papyrus" and the Dura Europos "shield". Each of these seems to have a different compass direction at top and it may be that a varying, ad hoc orientation is the hallmark of the pinax chôrographikos.

If this hypothesis turns out to be correct, it may be that we will be able reconstruct several more pinakes using the data in the Tabula Peutingeriana, which would mark a major advance in the study of early cartography.

You can see the graphic abstracts for eight of the TP cells on my website, as listed below. On each chart, press the "landmass-on" button to see how the layout compares to the geographical situation.

- Africa Romana revisualized

- Italia revisualized

- Gallia Togata to Noricum revisualized

- Aquitania and Provincia revisualized

- Graecia revisualized

- Asia Proconsularis revisualized

- Bithynia to Euphrates revisualized

Each of these revisualizations may give at least the layout of what might have been drawn on an early pinax.

The more immediate object of this research is however to focus on the creation of the TP, which might have taken place as follows:

- The compiler copied pinakes of all the regions of interest;

- Using texts, he copied travel itineraries onto the pinakes and connected the sheets without concern for the compass orientations.

- His final copy of this assemblage drastically reduced the height of the chart to the TP as we see it.