Do all roads lead to Rome? Not with the Peutinger Diagram. In neither sense of the phrase.

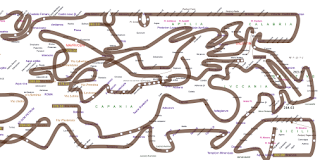

In Africa as depicted on this extraordinary late antique geographical chart (see

Talbert's digital version), the roads do not even point toward Rome. They run from east to west, ending at dusty forts on the desert's edge. I

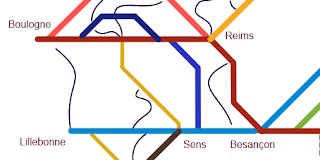

simplified their layout to a system diagram (below), showing how the chart-maker emphasized an array of parallel routes and inserted only occasional connections between these main lines.

By contrast, in Italy,

nearly all the highways lead to (or depart from) Rome. That appears to have been a guiding inspiration when the chart-maker was laying out the routes from the Alps to the gates of Rome. But as will see from my latest

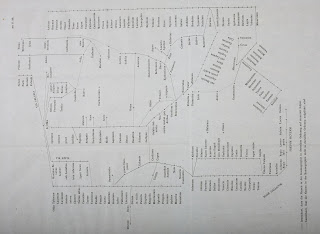

system diagram, this one for Italy (it has just gone online), there are some important exceptions.

To make these system diagrams, I squeeze the Tabula like a concertina. The Tabula (surviving in a single manuscript, Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis 324) is a very long roll, to be read in the horizontal. Eliminating that longness and adding some height enables us to see the network structure at a glance and comb apart the manuscript's jagged thickets of connections.

The limit of my squeezing is always the point where

the slightly sloping lines in the original rear up to an angle of 45

degrees from the horizontal, since the most useful outcome is a spider

diagram that resembles the London Underground network diagram. The horizontal scale is thus reduced and the crooked lines are regularized into a grid, but no other re-arranging is permissible.

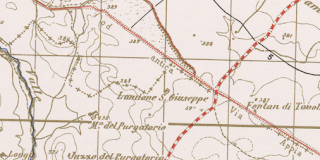

One use of this assay procedure is to test how proportionate to the geographical landform the Tabula is. One can put the peninsula's outline on screen (anchored to Milan: press the radio button next to "landmass" to "on") and see that at one-fifth the width, the match is surprisingly good.

The grey shape you can see here is a silhouette of the coast which has been given a one-eighth turn so that the peninsula aligns horizontally. Look for the spur, heel and instep of Italy (the toe is out of sight). In the image above, you'll note that Naples (

Neapoli) has been

pushed too far downwards, and Rome and Benevento are

placed too far to the right, but all in all, this mapping is closer to

the real thing than the Underground diagram is to the real London.

I began with a proverb, all roads lead to Rome, which signifies that a

variety of methods produce the same result. That is of course untrue in information visualization, where two different renderings of the same data - a scale map and a network diagram - often produce a very different impression on us.

The purpose of reflowing the Tabula in this fashion is to reveal some of

its subtler graphic characteristics, which tend to escape notice when

we stare at the roll-form original. The great Theodor Mommsen did something similar in 1851 before he became Germany's most famous professor. In his paper, ‘Die Unteritalien betreffenden Abschnitte der ravennatischen Kosmographie’, he rectified the Tabula layout much as I have done. (The job must have caused extreme stress to the printer.)

My systemic view is both more useful (with overlays and links) and more rigorous. You will notice in my analysis is that I have classified the roads into major

(colored) routes with many stops (which I would argue derive from the original Tabula) and minor (black) cross-country routes with few stops, which are much more likely to be casual additions to the chart by later readers.

Reflowing will make features you have

overlooked pop out visually. It may also reveal if you have

misconceptions about the data. My first attempt at this stratification did expose a misconception. This concerned three land routes in southern Italy. The

original Tabula shows

Roma - Corfinio, Nares Lvcanas - Vibona Balentia (both olive green) and

Erdonia - Gnatie (dark blue) as sinuous, fragmented, error-ridden routes. I mistook these for write-ins by a later user or editor.

The compressed version shows that if these routes are straightened out, they fit snugly enough into the available space. The road to Corfinio is a fairly important path across the Apennines, while the

Nares - Vibona and

Erdonia - Gnatie connections run parallel to (and quite close to) their respective coasts.

Of the remaining thin black lines, some represent now indeterminate sub-networks, such as near Hostilia, where the Tabula's original layout has been lost, or one or two borderline cases, such as a detour through Todo (

Tvder), which may have been part of the first layout. But for the rest, I would argue they are no more than ancillary mark-up, not part of the primitive design.

I have already hinted at a related discovery: compared to the Mezzogiorno, a disproportionately greater width of the Tabula has been allocated to the parallel tracks from the Alps to Rome. Perhaps the chart-maker started at the left and ran out of room, but whatever the reason, the Mezzogiorno ended up being a crowded part of the chart where the three connections above had to be folded up to fit.

That in turn is a main reason why I could not compact the Tabula's southern Italy by a factor of more than 5, whereas it was feasible to compress the Tabula's Africa by a factor of 20. Compressing is done by opening an image of the Tabula in the Inkscape graphics program and using its Transform > Scale command to reduce the drawing to a stated percentage of its original width. Attempting to take Italia below 20 per cent caused some of the gently inclined paths to go nearly vertical.

The disproportion between the two parts of Italy may disprove one of my earlier arguments too. In a draft article, I pointed out this year that across the Tabula's thin, river-like Adriatic, southern Italian cities are shown opposite Dalmatian coast cities that are almost due north of them.

The red lines in this sketch show these matches. From northern Italy, the one match shown involves the shortest line to the closest point, whereas five cities of southern Italy are not matched to the closest towns opposite. Knowing that the Mezzogiorno has been pushed into a space on the Tabula that is not big enough for it, we can guess this (rather than the African point of view) may explain the poor correspondences.

The Dutch scholar B. H. Stolte (see

my missing manual) proposed nearly 70 years ago that the original Tabula was originally drawn scaled to one quarter of its present width. I am not entirely convinced by his argument, let alone his supposition that this applies to the whole chart, not just parts of it, although my system diagram demonstrates that compression is a possibility. I think it is simpler to assume that the chart-maker instinctively laid out most of his

Italia lines either horizontally or at an incline of about 11 degrees, which would suffice to account for the neat, 45-degree compass rose of alignments when we compress the Italia zone of the chart.

We know now that the Tabula is not a "map" of the Roman Empire's road system. It leaves out too many major roads to merit that description. Its over-selects roads that run lengthwise on the roll and neglects the oblique ones.

I imagine the chart-maker planning his design with ostraca - old scraps of pottery or writing material - writing names on each from

the itinerary texts and laying his scraps out in lines across the ground, a hypothesis I have already applied to the genesis of Great Stemma history diagram of antiquity.

Adopting the same approach as he had employed in Africa, the chart-maker drew the routes of northern

Italia as parallel tracks (and indeed ignored all routes that were not longitudinal). These are the five or six main strands north (to the left) of Rome. These parallel routes shift and join like channels in an estuary, but the parallel reticulate pattern, as I call it, prevails. The Great North Road, the wine-red route from Rome via

Fano and

Bononia (Bologna), necessarily has kinks, since it crosses from Rome to the Adriatic coast, then turn north-west.

The routes in the Mezzogiorno turned out to be less parallel and more reticulate than in the north of Italy. In my spider diagram, the shore roads and the road parallel to each in the hinterland are easy to see, but it is the cross-peninsular routes that now catch the eye.

Two of these cross routes (purple and red) lead northeastwards from the port of Salerno to the "spur" of Italy, ending at Pescara (

Ostia Eterni) and Siponto. These are not roads

to Rome, but roads to use when avoiding Rome. If my hypothesis that the Tabula was drawn in Africa is correct, these would instruct any travelers from Africa heading over to the Adriatic coast.

There's another enhancement to my spider diagram which researchers may find useful. We only possess a single manuscript of the Tabula, but we possess a text that is half useful: the so-called Anonymous Cosmographer of Ravenna wrote a dreary listing of world place-names, probably in the 8th century, in which large sections match the name series in the Tabula.

The

Cosmographia, which is the topic of Mommsen's paper already mentioned, does not directly help us to reconstruct the primitive version of the Tabula, which dates from five centuries earlier. But it does flag possible omissions or alterations in the Vienna manuscript. Because of its usefulness, I am offering an overlay where a brown line traces on the Tabula the places the

Cosmographia mentions.

To make this useful to future researchers, I have marked the missing names with white circles. If you haven't found them yet, there are three controls in the top left corner of my system diagram (

link again) which show and hide the layers: the spider layout, the outline of Italy, and the

Cosmographia order. You simply need to click or tap the radio button controls. Try not to display more than one at once.

And where does "All roads lead to Rome" come from? The

librarians at Notre Dame say:

The proverb "All roads lead to Rome" derives from medieval Latin. It was

first recorded in writing in 1175 by Alain de Lille, a French

theologian and poet, whose Liber Parabolarum renders it as 'mille viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam' (a thousand roads lead men forever to Rome). The first documented English use of the proverb occurs more than two hundred years later, in Geoffrey Chaucer's Astrolabe of 1391, where it appears as 'right as diverse pathes leden diverse folk the righte way to Rome.'

Mommsen, Theodor. ‘Die Unteritalien betreffenden Abschnitte der ravennatischen Kosmographie’. Berichte über die Verhandlungen der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaft zu Leipzig, Philologisch-Historische Klasse 3 (1851): 80–117.

72, a 3rd- or 4th-century manuscript. Part of it, containing sections of epistles Peter 1 and 2, was donated to Pope Paul VI in 1969. [My thanks to Brent Nongbri of Sydney (

72, a 3rd- or 4th-century manuscript. Part of it, containing sections of epistles Peter 1 and 2, was donated to Pope Paul VI in 1969. [My thanks to Brent Nongbri of Sydney (