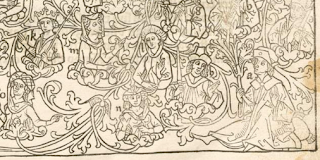

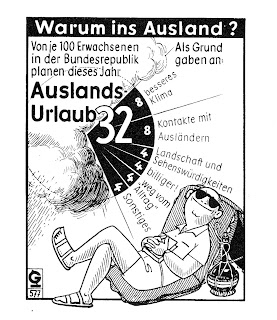

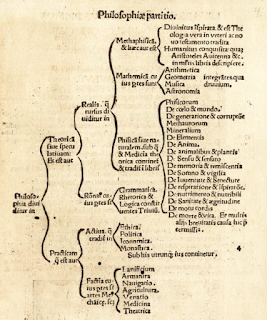

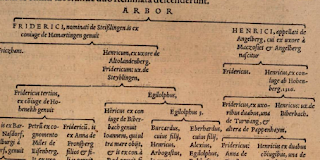

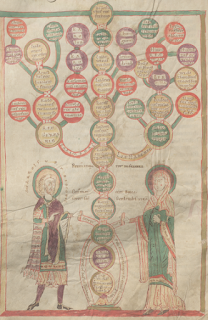

The search for the earliest use of "Baum" in German to describe a stemma continues. Currently the honour seems to reside with Heinrich Steinhöwel of Ulm who is thought to have used the term in his dedication of a book printed 1475 when introducing the following woodcut:

The male ancestor at the root, right, is designated Albrecht Hapsburg, landgrave of Alsace, Lord of Sassenburg. The main body of the book is a German translation of the Speculum Vitae Humanae of Rodrigo Sánchez de Arévalo (1404-1470). Steinhöwel's German title is Der Spiegel des Menschlichen Lebens.

It is online as BSB incunable 2 Inc.s.a. 1264 digitized here (seek image 18), also at the LOC and in Heidelberg. ISTC: ir00231000.

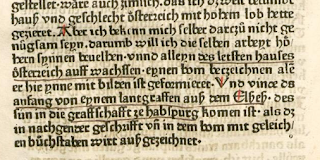

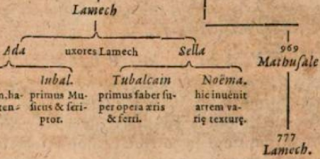

The text preceding the woodcut says: "darumb will ich ... alleyn desletszen hauses österreich auff wachssen eynen bom beczeichnen ale er hie ynne mit bilden ist geformieret. Und vince ds anfang von eynem lantgraffen aus dem Elses dessun in die graffschafft ze habspurg komen ist als dr in nachgenter geschrifft v[o]n in dem bom mit geleich-en büchstabben wirt ausgezeichnet. (That's why I wish to draw all of the latter house of Austria on a full-grown tree. Each is shown by pictures. And those counts of Hapsburg arising from this landgrave of Alsace are each marked in the tree with the same letter (of the alphabet) as is used in the subsequent list.)

This praise of the Hapsburgs is not part of the original Speculum Vitae Humanae itself (see the Latin version at Gallica), but an appeal for patronage from the Hapsburgs. Given that aristocrats were the principal customers for books in Steinhöwel's time, the genealogy was a crude but entirely normal attempt to secure sales.

No date or place of printing for the incunable is given, but it seems from the type-face to be settled that the printer was Günther Zainer of Augsburg, and that the year was most likely 1475. The translator's manuscript (which still exists) was completed March 19, 1474 and an entry in the genealogy on folio 10v mentions the baptism of Prince Maximilian in Augsburg "this Easter" on Maundy Thursday of 1475. It is to be assumed the printing was completed later that year. The book is overlooked by Klapisch-Zuber, who opens L'Ombre with a family tree of 1491 (see below), the earliest she could discover.

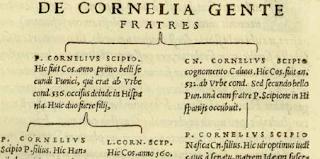

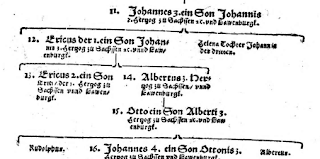

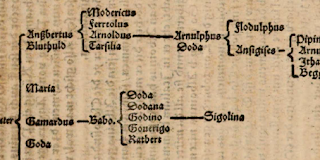

The book is prefaced by (1) a foreword and overview, (2) a dedication to Duke Siegmund of Tyrol, (3) a one-paragraph explanation of the family tree, (4) the full-page engraving, and (5) a tabular listing of the genealogy keyed to the sketch. (4) and (5) appear to be the work of Ladislaus Sunthaym (ca. 1440 – 1512).

Walther Borvitz is dismissive of (2) as fawning hack-work, which perhaps leads him to his peculiar view that (3) is a boiler-plate insertion originating with Sunthaym. Perplexingly, he refused to transcribe (3) in his edition (Archive.org) although it continues in the same first person (ich) as the paragraphs above and is almost certainly of a unity with them. It is hard to follow Borvitz's justification for this omission, since his contention that the text of (3) appears at col 1004 of Scriptores Rerum Austriacarum Veteres ac Genuini, vol 1, by Hieronymus Pez does not seem to be correct. The Latin text there is by Pez and makes no claim at all about the Steinhöwel book of 1475:

For the time being it seems best to leave the authorship of (3) with Steinhöwel. Perhaps an expert on Renaissance German style could ponder the issue.

The woodcut employed at Basel in or after 1491 for the printing of Der löblichen Fürsten und des Landes Österreich Altherkommen und Regierung (full text on Wikisource) of Sunthaym is not the same as this one, though it is similar. Sunthaym is often treated in the literature as father of the royal "tree", but it would seem that the "tree" was already part of the vocabulary of man one generation older.

The male ancestor at the root, right, is designated Albrecht Hapsburg, landgrave of Alsace, Lord of Sassenburg. The main body of the book is a German translation of the Speculum Vitae Humanae of Rodrigo Sánchez de Arévalo (1404-1470). Steinhöwel's German title is Der Spiegel des Menschlichen Lebens.

It is online as BSB incunable 2 Inc.s.a. 1264 digitized here (seek image 18), also at the LOC and in Heidelberg. ISTC: ir00231000.

The text preceding the woodcut says: "darumb will ich ... alleyn desletszen hauses österreich auff wachssen eynen bom beczeichnen ale er hie ynne mit bilden ist geformieret. Und vince ds anfang von eynem lantgraffen aus dem Elses dessun in die graffschafft ze habspurg komen ist als dr in nachgenter geschrifft v[o]n in dem bom mit geleich-en büchstabben wirt ausgezeichnet. (That's why I wish to draw all of the latter house of Austria on a full-grown tree. Each is shown by pictures. And those counts of Hapsburg arising from this landgrave of Alsace are each marked in the tree with the same letter (of the alphabet) as is used in the subsequent list.)

This praise of the Hapsburgs is not part of the original Speculum Vitae Humanae itself (see the Latin version at Gallica), but an appeal for patronage from the Hapsburgs. Given that aristocrats were the principal customers for books in Steinhöwel's time, the genealogy was a crude but entirely normal attempt to secure sales.

No date or place of printing for the incunable is given, but it seems from the type-face to be settled that the printer was Günther Zainer of Augsburg, and that the year was most likely 1475. The translator's manuscript (which still exists) was completed March 19, 1474 and an entry in the genealogy on folio 10v mentions the baptism of Prince Maximilian in Augsburg "this Easter" on Maundy Thursday of 1475. It is to be assumed the printing was completed later that year. The book is overlooked by Klapisch-Zuber, who opens L'Ombre with a family tree of 1491 (see below), the earliest she could discover.

The book is prefaced by (1) a foreword and overview, (2) a dedication to Duke Siegmund of Tyrol, (3) a one-paragraph explanation of the family tree, (4) the full-page engraving, and (5) a tabular listing of the genealogy keyed to the sketch. (4) and (5) appear to be the work of Ladislaus Sunthaym (ca. 1440 – 1512).

Walther Borvitz is dismissive of (2) as fawning hack-work, which perhaps leads him to his peculiar view that (3) is a boiler-plate insertion originating with Sunthaym. Perplexingly, he refused to transcribe (3) in his edition (Archive.org) although it continues in the same first person (ich) as the paragraphs above and is almost certainly of a unity with them. It is hard to follow Borvitz's justification for this omission, since his contention that the text of (3) appears at col 1004 of Scriptores Rerum Austriacarum Veteres ac Genuini, vol 1, by Hieronymus Pez does not seem to be correct. The Latin text there is by Pez and makes no claim at all about the Steinhöwel book of 1475:

Harum Tabularum Clauftro Neoburgensium praecipuus Auctor est Ladislaus Sunthaim seu Sundheimius, Ravensburgio Sueviæ oppido oriundus, Dioecesis Constantiensis Presbyter. Quod mirum est in laudatarum Tabularum editione fuisse dissimulatum: cum in MS Claustro-Neoburgensi quod nos coram inspeximus, diserte Sunthaimii nomen, patria conditioque habeantur. Porro eas Sunthaimius condidit sub annum 1491, quo ipso Basileæ typis excusæ fuerunt in majori forma, quam vocant. Ad cuius editionis fidem & hanc nostram adornavimus, cum sæpe memoratæ Tabulæ manuscriptae vix commodum Mellicium perferri potuerint, & nos, dum in lustranda Claustro-Neoburgensi Bibliotheca versaremur, ab ipsis integris describendis angustia temporis exclusi fuerimus. In vulgatis Tabulis ad calcem, Reverendissimus Dominus Jacobus Praepositus Clastro-Neoburgensis ad eas concinnandas symbolam contulisse memoratur, qui ab anno 1485 usque ad annum 1509 Claustro-Neoburgensem praefecturam gessisse dicitur apud Adamum Scharrerum in Vita S. Leopoldi Auftriæ Marchionis. Cæterum Ladislaus Sunthaimius is præterea fuit, qui Historiam de Guelfis sub annum 1511 composuit, quam ex Caesarea Bibliotheca fecum communicatam Cl. Leibnitius Tom. I Script. Brunswic. a pag 800 ad pag 806 publico exposuit. Ex qua etiam intelligimus, Sunthaimium postea Viennensis Canonici dignitate fuissse auctum. Sed de his fatis. En ipsas Tabulas Claustro Neoburgenses.There is thus no reason to attribute (3) to Sunthaym, and every good reason to regard Steinhöwel as the writer who chose the word "bom". Barbara Weinmayer offers a very different perspective on the section (3), seeing the dedication as a valuable source of Steinhöwel's genuine views about the science of translation, although she makes no comment on the content of our disputed final paragraph (3) and its bom.

For the time being it seems best to leave the authorship of (3) with Steinhöwel. Perhaps an expert on Renaissance German style could ponder the issue.

The woodcut employed at Basel in or after 1491 for the printing of Der löblichen Fürsten und des Landes Österreich Altherkommen und Regierung (full text on Wikisource) of Sunthaym is not the same as this one, though it is similar. Sunthaym is often treated in the literature as father of the royal "tree", but it would seem that the "tree" was already part of the vocabulary of man one generation older.

Borvitz, Walther. Die Übersetzungstechnik Heinrich Steinhöwels: dargestellt auf Grund seiner Verdeutschung des ‘Speculum vitae humanae’. Hermaea 13. Halle: Niemeyer, 1914.

Dicke, Gerd. ‘Steinhöwel, Heinrich’. Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon, 1995. vol 9, cols 269ff. http://www.mgh-bibliothek.de/cgi-bin/mgh/allegro.pl?db=opac.

Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane. L’ombre des ancêtres. Paris: Fayard, 2000.

Weinmayer, Barbara. Studien zur Gebrauchssituation früher deutscher Druckprosa. Literarische Öffentlichkeit in Vorreden zu Augsburger Frühdrucken. Munich: Artemis, 1982.