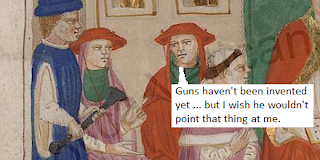

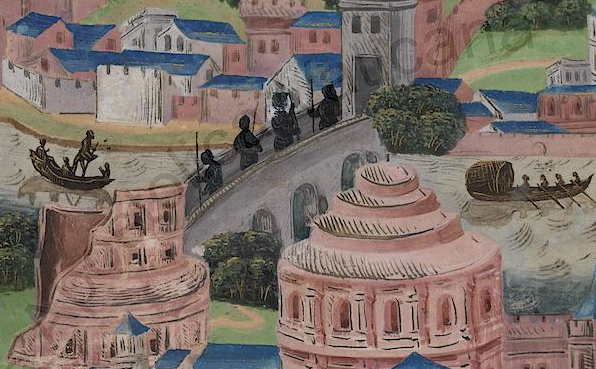

Our latest investigation concerns a curious courtroom scene possibly drawn by Nicolò da Bologna in Urb.lat.160 at folio 5r. I introduced this manuscript in November 2015 when it was brought online by Digita Vaticana. The St Louis catalog discusses the codex in some detail, as does Stornajolo's Codices Urbinates Latini, Codices 1-500, pp 166-167.

The caption under the scene says "Bonifatius". The miniature appears on the opening page of the Liber Sextus, a compilation of decretals issued under the authority of Pope Bonifatius (Boniface) VIII in 1298.

The text on the two columns of this manuscript page has not been fully set up in print since 1582 but can be easily read in a reproduction in the UCLA Digital Collections here at the UCLA Library.

The manuscript dates from about 1380, but the anonymous St Louis cataloger thinks the art may be from 50 years later, noting "The Liber Sextus appears to be written around the same time, but its

decoration was probably executed in the 15th century, around 1420-1440,

in northern Italy, perhaps Ferrara."

Who is the man in the blue tunic on the far left of the image? My interpretation of the scene is that it shows Bonifatius at centre consulting his law book. Kneeling in front of him are two advocates. The advocate at right is pointing to the woman and is apparently speaking on her behalf. The left advocate appears to represent the man in the blue hat. The setting is Renaissance Italy.

It would be plausible to suppose the two litigants are husband and wife, as couples were frequent parties in canonical courts. The other four seated men in red hats appear to be part of the panel of judges. They are evidently listening to what is being said. The room is low and has a daytime garden visible through the four windows, but that is probably an artistic framing device only, not a real location.

What is going on? The man in blue on the left is scowling. The woman has drawn up her skirt to expose her hem, her blue-slippered foot and an ankle. Perhaps she is avowing she has nothing to hide. @zippyman818 notes that her white/blue garment is the opposite in decoration to the man's blue/white combination at the hem, which must symbolize some irreconcilable difference.

Both man and woman are wearing blue slippers. They are both clearly well-off. And here is the big question: what is the man holding?

It's black, it has a bulb at the bottom left end and it looks as if it is about 60 centimetres long. @zippyman818 and I have been having some fun in a Twitter exchange (expand from this one to see the whole conversation) trying to work out the puzzle.

The first consideration is whether it might be a gun. The first firearm in Europe was the arquebus, and I read that it was employed in the army of Matthias Corvinus, which might get us back to a date of 1460. But this image long predates that, and in any case the object does not have a hook, which is essential to cope with gun recoil (and muzzle loading), and the bulb cannot have a function in any firearm.

Another early answer was a horn, but there is no mouthpiece on the thing. Again the bulb is the puzzle. It's not a klaxon, as rubber bulbs had not been invented. Besides why would a rich litigant take a horn to court? @zippyman818 has also suggested a long-handed chisel or a herb cutter with a mezzaluna blade, but again, why would the pope let you bring one into his courtroom?

[A completely different approach proposes that the object is ceremonial in nature. The arguments are set out in the comments below. Armin argues that it is a sconce, a kind of torch (in case the trial goes on past nightfall?) Ilya Graubart is proposing a mace (if medieval popes had armies, perhaps they had maces or sceptres as well). These arguments would suggest that Mr Blue Tunic is not a litigant, but maybe the pope's majordomo or some other papal panjandrum.]

It has been suggested the black thing might be an artistic emblem identifying some historic person who sought justice from the real-life jurist Bonifatius, or a speaking stick entitling the person to hold the floor, but Blue Tunic's mouth is shut. Or it might be a ritual object like an aspergillum or some entirely forgotten symbol.

My own tendency is believe it is an item of evidence connected to a marital lawsuit, perhaps a sword scabbard. Is the wife being accused of adultery with the sword's owner perhaps? At this point we become fanciful. But clearly, when the miniature was drawn, this object was immediately recognizable and perhaps it even elicited a laugh from the Renaissance reader.

Disgrace

8 minutes ago