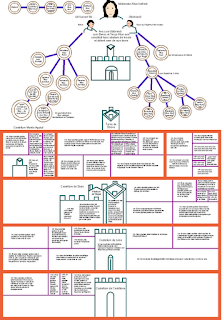

Readers may recall that I published online last year the ur-text of the Liber Genealogus of 427 (link). It is not a critical edition, but it is the first to present the archetypal text of the year 427 without clutter. Those who follow this blog will know that the Liber Genealogus is a strange chronological and genealogical tract which can only be understood if one realizes it was a learned commentary on a wondrous drawing: the Great Stemma.

In 2002, the eminent Italy-based historian-philologist Dr Michael Gorman published an article in the journal Scriptorium on 11th-century manuscripts from the monastery at Monte Amiato, a Benedictine community which was closed in 1782. He argued that three very similar codices had all been drafted in the scriptorium there in the 11th century. His article was re-published in Italian with some revisions in 2007.

The third of the manuscripts which he highlighted was one that had escaped the notice of Theodor Mommsen when he published his edition of the Liber Genealogus at the end of the 19th century. This manuscript at Cesena doubtless contains a copy of the F recension. Giuseppe Maria Muccioli writes in that library's printed catalogue that the text begins: Genealogia totius Sacra Scripturae, cum persecutionibus Christianorum, which echoes the Madrid incipit, Genealogiae totius bibliothecae ex omnibus libris veteris novique testamenti. I discussed the Madrid version in a post in February.

Here is a tabulation of the parallel contents of the three codices, based on the publications of Dr Gorman, Mommsen and Professor José Carlos Martín. The three columns at right represent the folio numbers in:

- Plutei 20.54

- Conv. soppr. 364

- Cesena D.XXIV.I (Catalog)

| Isidori Hispalensis | Etymologiae (ed. Lindsay) | lost | 1- 100v | 1- 183 |

| Junilius Africanus | De partibus divinae legis = Instituta regularia divinae legis (CPL 872) (Collins) | 1ra - 8rb | 100v- 107 | 183- 193v |

| Bede (thus identified by Gorman) | Glose per totum alphabetum (Gorman reference: De ortographia, ed. CCSL 123A.7-57) | 8rb – 15rb | 107- 111v | 193v- 201v |

| Anon | Glossa super Octateuchum et Librum Regum (Glossa Rz: see Holtzmann) | omit | 111v- 116 | 202- 209v |

| Anon | Divisiones temporum XIII (unpublished) | 15rb – 21ra | 116- 120 | 209v- 217 |

| Isidori Hispalensis | Ety. 6.3.2: ''Bibliothecam ... Esdras scriba ...." | 21ra | 120 | 217 |

| Isidori Hispalensis | Ety. 7.1.2-37 and 7.2.11-49 | 21ra – 22va | 120- 121v | 217- 219 |

| Anon | De litteris (grammatical tract on syllables, vowels, consonants: Qui primum interrogandum est his qui scientiam divinarum scripturarum scire desiderant...) | 22va – 24ra | 121v | 219- 220v |

| Anon | Liber Genealogus (CPL 2254) (ed. Mommsen MGH chron. min I, pp 160-196; ed. Piggin) | 24ra – 30ra | 122- 125v | 220v- 228r |

| Isidori Hispalensis | Chronographia, cum prologo; (ed. Martin) | 30ra – 34ra | lost | lost |

| Anon | Catalogus regum Langobardorum et Italicorum Lombardus (ed. Waitz MGH scr. rer Lang.) ends with last Italian kings Lothair II and Berengar II and the crowning in 961 of Otto II as overlord of Italy | 36va – 37ra | lost | lost |

| Anon | Great Stemma (ed. Piggin) | 38r – 45r | lost | lost |

| Pseudo-Julianus | Ordo annorum mundi (ed. forthcoming, Martín) | 45r | lost | lost |

It will be obvious from this that the first three-quarters of the Plutei 20.54 manuscript has been lost, whereas the other two manuscripts are lacking their final quarter or third. The folios which we now see numbered 1-45 in the online digital version of Plutei 20.54 were numbered 143-187 when the codex was intact. Possessing all three codices allows us to reconstruct the lost model at Monte Amiato from which they must have been copied.

Gorman notes that the Divisiones temporum XIII above is a text with an annus praesens of 745 CE, matching the legendary date of foundation of the monastery, and argues that this, along with other formal criteria, establishes a clear link between this miscellany and the presumed 11th-century Monte Amiata scriptorium.

Gorman's article is also of interest for its discussion of a medieval diagram which is based on the Great Stemma but adds new content. It was probably made in the same scriptorium. This is found in another Florence manuscript, Cod. Amiatinus 3, ff 169-172v (not online). He notes that this diagram's list of popes finishes with Agapetus (papacy 946-955), and conjectures that this information was drawn from yet another extant manuscript that had been made and kept at Monte Amiata, plut. 65.35, f 3r. (online) which contains a Liber pontificalis.

Note added in 2013: The latter manuscript is discussed in a later post.

Gorman, Michael. ‘Codici manoscritti dalla Badia amiatina nel secolo XI’. In La Tuscia nell’alto e pieno medioevo. Fonti e temi storiografici ‘territoriali’ e ‘generali’, edited by Mario Marrocchi and Carlo Prezzolini, 15–102. Florence: Sismel - Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2007.

------. ‘Manuscript Books at Monte Amiata in the Eleventh Century’. Scriptorium 56 (2002): 225–293: 268–271.

Martín, José Carlos. Isidori Hispalensis Chronica. Turnhout: Brepols, 2003.*67

Mommsen, Theodor, ed. ‘[Liber Genealogus:] Additamentum II [to the] Chronographus anni CCCLIIII’. In Chronicorum minororum saec. IV. V. VI. VII. Vol. 1. Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH), Auctores Antiquissimi (AA) 9. Berlin: Weidmann, 1892.