2016-10-01

Secret of Oldest Infographic Revealed: A Grid

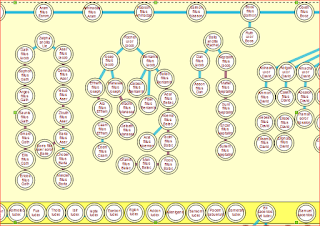

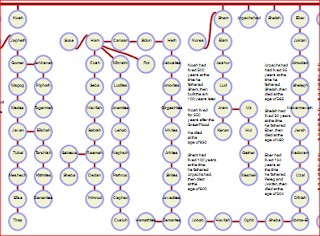

When I first announced its rediscovery in 2011, I presented a rather freely drawn plot of it (see this in my article in Studia Patristica or archived on my website as an swf (Flash) file):

This time round, I am trying to do something much harder: to replicate the chart without any accommodations to modern assumptions, showing it precisely as it was intended by its designer.

The result (link) is the layout that the designer would have saved if the SVG mark-up language had existed in the fifth century. Not only are the lines, circles and text in the precise locations where the design called for them to be positioned. These positions also allow us to observe the design's hidden concepts and rules. This new drawing is not an impression of the late antique original: it is an encoding of the design itself.

The starting point for my revision was wise counsel from a great infographics teacher and practitioner, Raimar Heber of Germany. Raimar has just published a textbook (in German, Rheinwerk Verlag) of best practices in infographics and it looks very good indeed from the page samples.

In 2011, Raimar offered to do a retro-engineering experiment: he world accept an imaginary design brief and visualize the data of the Great Stemma as one of the world's leading professional art editors would design it today. He drew up a graphic sampler. One frame of it pitched a grid as the basis of the visualization. Chains should be laid out in the horizontal and vertical, he argued, with shoots allowed at 45-degree angles if the going got tough.

For a long time, I was sceptical about this. It sounded too 21st century to me. There is only one manuscript of the Great Stemma where straight lines and right angles stand out (Plut 20.54 in Florence), but one tends to assume that was just the obsession of an over-neat scribe.

But in spring this year I began re-analysing every substructure of the Great Stemma using a selection of the best manuscripts. This involved no less than 30 separate investigations, listed here as a "detail views".

For the first time I noticed something.

The manuscripts contain many vertical columns of roundels (the circles containing names). If one counts how many members there are in such rows, one comes up unusually often with the number 10. There might for example be a column of eight connected roundels, in a place where two others above them block the area overhead. Or there are long chains which bend to the left or the right at the 10th member in many manuscripts.

So as an experiment I worked to trim all 100 of so columns of the Great Stemma so that each was 10 elements high. If you array that many columns side by side it naturally appears gridlike.

This alignment became a new paradigm. Not only is this pattern harmonious, but it also provides a simple and logical explanation for so many bulges, interlocks and elbows in the manuscripts. I am convinced it is the lost original pattern that the designer used. So Raimar's insight turned out to be spot on.

On reflection there would have been good reasons to use a grid. Firstly, it makes designs easier to read. That is an imperative of then and now.

Secondly, it makes a design much easier to hand-copy, which is no longer an imperative now, but was an important concern before the rise of printing. If you draw a grid where the written data expand neatly in two dimensions, and prescribe moreover that certain squares be left blank, you have a robust model for copyists to work from. We should study whether a similar method may have been used to copy the Peutinger Table, mappaemundi and other late antique charts by hand.

Take a look at my new reconstruction, which translates all of the 5th-century design into a (gridlike) pixel coordinate system. This design is not drawn by hand, but as output from a new database I have built, where all the crossing points in the grid have been recorded, along with the roundels, texts and connectors that pertain to those crossings. Other scholars may offer their own editions in future, but I would argue that the Piggin Stemma is the most accurate reconstruction on the available evidence.

A contemporary buzzword is digital humanities, which often is simply watered down to mean storing and searching old documents as scans in databases. True digital humanities work is something more: it means recasting historic creative work from its original analog expression to a digital expression which remains absolutely congruent with the artist's or writer's intentions, but yields more insight.

I have tried to make this chart even more accessible by translating its text into English and by supplementing it with explanatory plaques and interactive visual effects (look for radio buttons like those above). Tell me if it works like this and how you think it might be further improved.

2016-05-03

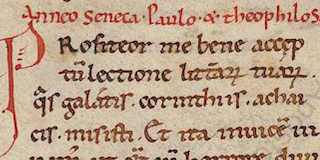

Seneca and Paul

Alcuin ( -804), the great English scholar, prepared an edition of the Correspondence. Whether he believed it to be genuine cannot really be divined, but in the high Middle Ages, this fiction was universally believed to be fact, and it was only the early humanists who dared point out that it was surely absurd to suppose the letters to be anything but a creative literary work.

The translation by Barlow, who denotes this manuscript as A in his 1938 edition of the correspondence, can be read at Archive.org.

The Latin letters are found at ff. 223v-225v of the newly digitized codex. Here is Seneca allegedly writing: "I must admit I loved reading your letters to the Galatians, to the Corinthians and to the Achaeans."

- Barb.gr.243,

- Barb.lat.1670, a 17th-century deed

- Borg.ebr.2,

- Borg.ebr.5,

- Borg.ebr.6,

- Borg.ebr.8,

- Borg.ebr.15,

- Ross.325, Torah, 15th century

- Ross.360, Mahzor, Sephardic rite, 15th century

- Ross.478, Haftarot, Italian rite, late 13th century

- Ross.533, Hebrew commentary on prophets, date about 1325

- Ross.1188, Hebrew Esther scroll, 18th century

- Ross.1189, early 18th century Esther scroll

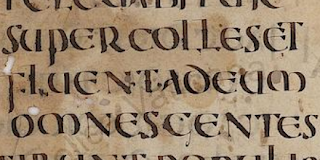

- Vat.lat.91, Peter Lombard, Glossae continuae in Psalmos?

- Vat.lat.251, ff. 1-1v: Leo Magnus, a fragment of Ep. 16; 2-223v: Hilarius, Tractatus super Psalmos; 223v-225v Epistolae Senecae ad apostolum

Paulum et Pauli ad eundem (the fictitious Correspondence between Seneca and St Paul); Barlow: XI cent., mm. 306 x 216, ff. I + 226.

The entire manuscript was copied by a single scribe

in two columns of thirty lines to the page.

A note in a different hand on f. 226v claims this codex was one of the books acquired

for the monastery of Avellana by Petrus Damianus while he was abbot

1041-1058, but Erik Kwakkel says that given the script of the codex (his book on the evolution of book hands), this date cannot be true:

@JBPiggin great manuscript and case, but the BAV catalogue is wrong about the date: it's 12th century (just FYI).

— Erik Kwakkel (@erik_kwakkel) May 4, 2016 - Vat.lat.352,

- Vat.lat.622,

- Vat.lat.625,

- Vat.lat.626,

- Vat.lat.627,

- Vat.lat.630.pt.1, Isidorus Mercator Decretalium collectio

- Vat.lat.638, Venerable Bede, 11th century ms, In Lucae Evangelium expositio, praeviis litteris

- Vat.lat.661, mainly Bernard of Clairvaux, 15th century manuscript

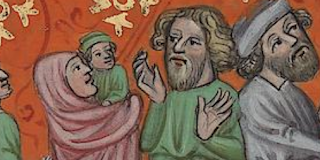

- Vat.lat.681, Sentences of Peter Lombard, with this couple (she is in a blue wedding dress, note her short veil) making their marriage vows, both left hands on the bible:

Baschet notes that it is very rare to find a 12th century depiction of the vows being recited.

2016-04-12

Trio of Vergils

It has just entered the internet, marking a fresh historic moment in the Vatican digitization program. On the same day, the Vatican's leaves of a non-illuminated Virgil from the same period, the Vergilius Augusteus (Vat. lat. 3256), arrived online.

The even older Vatican Vergil, Vat. lat. 3225, another Late Antique illustrated book with which these two are commonly compared, has been online for over a year. These two additions make the set complete. Now you can compare all three at high resolution, in colour.

Classical Rome did not have illustrated codex books. Late Antiquity invented them in one of its major advances in media and public education. The rest as they say is history.

Here is the Roman Vergil's treatment of a shipbound Aeneas enduring a storm released by the goddess Juno against him. It is often said that the style seems like a precursor to medieval art:

The Wikipedia article Vergilius Romanus notes a theory that the Roman Vergil was made in Britain. Robert Vermaat accessibly sums up the argumentation for this. If true, the Roman Vergil is the oldest of any book from England in existence.

Here is the full list of 143 digitizations on April 11, bringing the posted total to 4,215. Click (tap) on the images to go straight to the pages. I want to rush this major news to you now, and will continue to mark the list up, with more of the goodies to be described in the next few days, so do come back.

The Bibioteca in Rome has no RSS feed, no running announcements, nothing. If you want news on what they put out, you'll have to come to my unofficial site, the only news stream on the internet covering the subject. Follow me on Twitter: there's a one-click button at right to make it easy.

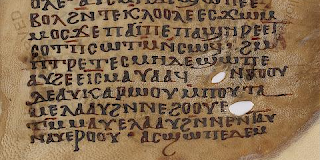

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XVI.fasc.59, fragments, Gospel of Luke 8:36-9:41 and 12:39-14:9, looking extremely old even to my untrained eye

- Chig.C.IV.100,

- Urb.lat.603, the Breviary of Blanche of France, a major art treasure

- Vat.lat.29 ,

- Vat.lat.268,

- Vat.lat.284,

- Vat.lat.287,

- Vat.lat.303,

- Vat.lat.317,

- Vat.lat.326,

- Vat.lat.333,

- Vat.lat.335,

- Vat.lat.357,

- Vat.lat.358,

- Vat.lat.359,

- Vat.lat.361,

- Vat.lat.363,

- Vat.lat.365,

- Vat.lat.367,

- Vat.lat.370,

- Vat.lat.374,

- Vat.lat.379,

- Vat.lat.383,

- Vat.lat.386,

- Vat.lat.387,

- Vat.lat.388,

- Vat.lat.390,

- Vat.lat.391,

- Vat.lat.394,

- Vat.lat.395,

- Vat.lat.402,

- Vat.lat.403,

- Vat.lat.404,

- Vat.lat.406,

- Vat.lat.408,

- Vat.lat.411,

- Vat.lat.417,

- Vat.lat.419,

- Vat.lat.420,

- Vat.lat.421,

- Vat.lat.422,

- Vat.lat.423,

- Vat.lat.426,

- Vat.lat.429,

- Vat.lat.431,

- Vat.lat.432,

- Vat.lat.437,

- Vat.lat.442,

- Vat.lat.443,

- Vat.lat.447,

- Vat.lat.448,

- Vat.lat.455,

- Vat.lat.456,

- Vat.lat.457,

- Vat.lat.460,

- Vat.lat.462,

- Vat.lat.464,

- Vat.lat.469,

- Vat.lat.470,

- Vat.lat.473,

- Vat.lat.477,

- Vat.lat.482,

- Vat.lat.488,

- Vat.lat.492,

- Vat.lat.493,

- Vat.lat.497,

- Vat.lat.499,

- Vat.lat.502,

- Vat.lat.503,

- Vat.lat.504,

- Vat.lat.506,

- Vat.lat.508,

- Vat.lat.509,

- Vat.lat.511,

- Vat.lat.512,

- Vat.lat.515,

- Vat.lat.517,

- Vat.lat.520,

- Vat.lat.522,

- Vat.lat.523,

- Vat.lat.524,

- Vat.lat.526,

- Vat.lat.528,

- Vat.lat.529,

- Vat.lat.530,

- Vat.lat.531,

- Vat.lat.532,

- Vat.lat.536,

- Vat.lat.537,

- Vat.lat.538,

- Vat.lat.541,

- Vat.lat.542,

- Vat.lat.547,

- Vat.lat.548,

- Vat.lat.551,

- Vat.lat.553, Eucherius of Lyon, a 9th-century manuscript possibly originating from Germany. Lowe number, CLA 1 6

- Vat.lat.554,

- Vat.lat.559,

- Vat.lat.562,

- Vat.lat.570,

- Vat.lat.574,

- Vat.lat.579,

- Vat.lat.583, Gregory the Great in an 8th-century manuscript, Lowe number CLA 1 7, with this fine fishy Q:

- Vat.lat.589,

- Vat.lat.590,

- Vat.lat.591,

- Vat.lat.595,

- Vat.lat.605,

- Vat.lat.607,

- Vat.lat.608,

- Vat.lat.613,

- Vat.lat.614,

- Vat.lat.621,

- Vat.lat.643,

- Vat.lat.1112, commentary on the Sententiae

- Vat.lat.1164, theological including Giacomo da Pesaro

- Vat.lat.1165, theological, first half is a Spanish printed book of 1548

- Vat.lat.3198, Petrarch with portrait:

- Vat.lat.3212, Italian poetry of Antonio del Alberti, etc.

- Vat.lat.3256, the Vergilius Augusteus (see the Wikipedia article)

- Vat.lat.3305,

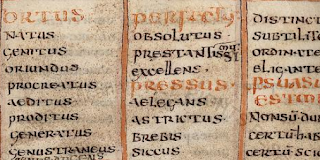

- Vat.lat.3321, a late antique glossary, in an 8th-century central Italian manuscript, Lowe CLA 1 15: a sort of dictionary and Roget's Thesauraus combined. I originally marked this as Isidore of Seville, Differentiae (Isidore was a bit of a plagiarist and fond of substituting new words in quotes to make them his own) but it seems that this is a source used by Isidore. The manuscript has been edited (see the 1834 Rome edition on Google Books) and there is a huge bibliography suggesting this is an important source for Latin lexicography and linguistics.

- Vat.lat.3357,

- Vat.lat.3437,

- Vat.lat.3773: Thanks to ParvaVox who was quick to point out this is an old pictorial Mexican Nahua manuscript, and to @carolinepennock, who adds that it's a tonalamatl (divinatory calendar), probably from Tlaxcala. She says it is one of only a handful believed to be pre-conquest, and another digital reproduction is available at www.famsi.org. It was probably made in the 16th century, but the manuscript's history previous to the Vatican cataloguing of 1596-1600 is unknown. She says it part of what is called the Borgia group. Here's one of the hundreds of figures in it:

- Vat.lat.3797,

- Vat.lat.3867, the Roman Vergil, in rustic half-uncial script with many illustrations (see above)

- Vat.lat.3869, Hippocrates' Iusiurandum translated to Greek: ETNG

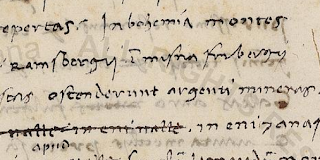

- Vat.lat.3886, Enea Silvio Piccolomini's 1458 autograph manuscript of Germania, a famed humanist review praising the orderliness and prosperity of the new Germany. It was to appear in print in Leipzig in 1496. This second part is marked Aeneas Cardinalis Sancte Sabine ad objectiones Germanorum in a 16th-century hand on the front flyleaf. See Gernot Michael Müller

- Vat.lat.4104, 16th-century letters to Angelo Colocci, Fulvio Orsini and others

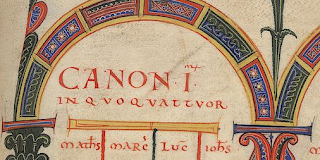

- Vat.lat.4221, 11th-century three-column bible, possibly with some Vetus Latina readings, with fine canon tables:

- Vat.lat.4329, folio 87, a flyleaf, is a recycled 7th- or 8th-century page with Liber Comitis on it, Lowe number CLA 1 20:

- Vat.lat.4777, Dante? incomplete

- Vat.lat.4782, Dante, two-column ms

- Vat.lat.4965, the 9th-century report/translation from the Greek concerning the 8th Ecumenical Council in Constantinople for Pope Hadrian II by Anastasius Bibliotecarius: he seems to have got scribes in the papal scriptorium to write up this fair copy 870-871, then wrote his corrections on it. With these remarkable alterations, this manuscript offers insights into a first-millennium translation bureau (link to Berschin). HT as well to @LatinAristotle who flags a major article by Réka Forrai about this papal translator and diplomat.

- Vat.lat.5697, Peter Comestor's Historia Scholastica , early 15th century, one of the masterpieces of Gothic illumination, with wonderful images such as this scene:

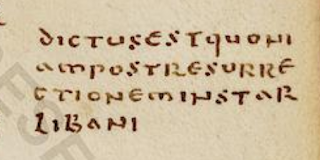

This is a charming Eve about to bite the apple as the Devil tells her it's sooo good: Notice the selfie-like distortion? Please, somebody, post this on Instagram. - Vat.lat.5704, a 6th-century Latin translation of Cassidorus's Historia Tripartita almost certainly made in his own scriptorium at Vivarium, Italy. Lowe number CLA 1 25. It has been argued by some scholars that marginal notes to the Enarratio in Canticum Canticorum of Philo Carpasianus may be by the hand of the great Cassiodorus himself: If we had not had the Vergils, I would certainly have headlined this week's post with this treasure.

- Vat.lat.5759, Ambrose of Milan on Genesis and the Evangeliorum Libri of Juvencus, late 10th century, written over the top of an 8th-century gospels probably from Bobbio, Italy. The final pages have not been refilled, so you can see clearly how a palimpsest was prepared. Lowe number CLA 1 37

- Vat.lat.7016, an 8th-century gospels from Italy intact, Lowe number CLA 1 51 with canon tables:

- Vat.lat.7189, commentary on canon law by Johannes de Turrecremata (died 1468): the missing volume of an autograph series Vat. lat. 2572-2576 (Gero Dolezalek).

- Vat.lat.11258.pt.B, a book of designs and plans for baroque Rome. Anthony Grafton notes in the Rome Reborn catalogue that this architectural drawing (folio 200r) for the centrepiece of the Piazza Navona by Francesco Borromini was not implemented.

- Vat.sir.598, an 1871 copy of records of 19 oriental synods

- Vat.turc.150,

2015-03-25

Prudentius and the odd word

Sometimes, though, when you are busy with a topic, a particular manuscript suddenly expands in importance and seems like missive from the past directed at you personally.

I am writing a book about the invention during antiquity of node-link diagrams. The book mentions the probable Latin term for such a diagram, stemma. This is not a book about linguistics, but you need to make sure there is no unseen linguistic evidence lurking there.

As often happens in research, both journalistic and scholarly, you can spend a whole day combing the forest for a catch and come home empty-handed.

In this case, there is no trace of anyone living during antiquity proper who calls one of these diagrams a stemma. My book will simply skip the whole matter, because it will not be an academic thesis and will only concentrate on the fruitful and interesting things I found. What I did discover about the word, I lodged as a bunch of notes in a new page on my website. I don't need such notes, but I routinely archive such things because they might help someone else some day.

What that page says is that stemma meant:

- a garland of leaves, straw, wool or other materials (in Greece)

- a niche in a Roman palazzo containing paintings of noble ancestors (in the Republic)

- a snob's genealogy (under the Empire)

- ancient glories (in literary vocabulary in Late Antiquity)

- a twig-like node-link diagram as drawn by lawyers (in 620 CE)

The Hymnus Epiphaniae can be conveniently read in full at the Perseus Digital Library if you read Latin.

The Australian coast of Victoria has got a famed set of rocks, the Twelve Apostles, off the shore of the Port Campbell National Park, and South Africa has a Twelve Apostles Range, but Prudentius (348-about 405) seems to have beaten both to the name. Perhaps pilgrims did once get such a feature pointed out to them in the Jordan. [Late addition: It seems Prudentius is referring to the biblical Book of Joshua, the writer of which says 12 stones were taken from the Joshua in the river and placed nearby and are "still" there.]

Why does the poet call the 12 rocks a stemma of the apostles? Could he have possibly meant:

- an ancient glory of apostles?

- a node-link diagram of apostles?

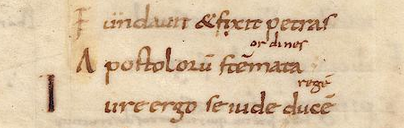

As it happens, a bunch of manuscript releases by Digita Vaticana this week (here's my news item) includes a manuscript of Prudentius's poetry. Cilian O'Hogan says it is actually an important one:

Vat Reg 321, an important MS of Prudentius, now digitised http://t.co/DRL5Cv5fwZ (via @JBPiggin) pic.twitter.com/WEKbVtoFHh

— Cillian O'Hogan (@CillianOHogan) March 24, 2015

What makes codex Reg. lat. 321 so interesting is that its 10th-century editor has packed it with glosses and annotations. What I liked was that the editor seemed to have been baffled by the odd word "stemmata" too. He glossed it with the meaning "ordines" written above it here.I'm still not clear about this. A similar word does show up in one description of the Great Stemma, Genealogia ab Adam usque ad Christum per ordines linearum. But I doubt if Prudentius had diagrams in mind. More likely the poet simply imagined those rocks in a orderly row or circle to represent the rock-like perpetual authority of the church. Stemma (ancestry) was a way to say in the language of Latin poets that the rocks were a precursor to the apostles [as Daly argues].

All very arcane, and from the manuscript, I knew that an unknown editor of 1,000 years ago had been baffled and had also done his best to unpuzzle Prudentius's odd word.

2014-02-24

Italian Digressions

Chronographs often resemble Wikipedia articles that were originally conceived as harmonious texts and then acquire additions which various officious readers decide it "would be good to have as well". The result is usually a lopsided mess. Wikipedia neatly allows its readers to compare versions and even undo the more foolish and self-indulgent digressions. Late Antique manuscripts do not come with such conveniences.

That makes it an intellectual challenge to unwind this process of accumulation. As Professor Burgess demonstrates with his analyses of chronographs, this can sometimes succeed.

Readers of this blog will recall that the Great Stemma is an early fifth-century chronographic diagram where the reader can see the whole course of biblical history at a glance, somewhat like the divine vision omnis etiam mundus ... ante oculos eius adductus est (the whole world placed before the eyes, in Gregory the Great's phrase for an overview of the whole human condition at a glance).

The Great Stemma seems to have developed in parallel with the Liber Genealogus of 427. Digressions quickly developed in both.

The first edition of the Liber Genealogus (datable because it mentions the Roman consuls of 427 as the very latest ones) was exclusively concerned with the biblical timespans.

The LG edition of 455 (which gives its date as the 16th year of the reign of Genseric as well as the year of death of Valentinian III) throws in for no apparent reason a long witty anecdote from 1 Esdras 3. What has this debate about the comparative merits of booze, power, sex and truth at the Emperor Darius's feast got to do with chronography?

Perhaps the answer lies in the Esdras story's conclusion: that truth endures and is strong forever? Or is the whole digression an erudite game, where each editor of the LG chases up a topic initiated by his predecessor? You tell me a story about the Jews and Darius, I'll tell you a literary Darius story back.

The digressions do not stop. The LG same edition of 455, represented by a single manuscript now preserved at Lucca, Italy, also digressively inserts a list of kings of Rome. This kind of list is generally termed an Ordo Romanorum Regum. What we don't fully understand is why Late Antique writers felt the urge to insert this seemingly irrelevant information into annalistic documents.

Some years ago I wrote an article on a similar "Italian digression" which seems to have been added to the Great Stemma. What have ancient Roman kings got to do with biblical history? Their dates don't help you to figure out the age of the world, or the antiquity of Judaism. Perhaps it is something merely ideological. Maybe 5th-century Christian writers felt a need to flaunt their knowledge of early Roman history as an expression of their patriotic allegiance to the Christian empire and their revulsion for the barbarian Germanic invaders who were disrupting the old order.

We don't really know the answer. But digressions may give us a feeling for the issues that preoccupied a generation of editors, just as alterations to Wikipedia articles often give you a picture of what kind of people are hiding behind the pseudonyms and what the Wikipedians' obsessions are.

2013-06-23

New Eusebius Tables Coming Out This Year

I think this must be Fridegar Mone (1829-1900), since that is the name on the edition of 1855. I wondered for a while if it was not the father, Franz Mone (1796-1871). Both men had fascinating, conflict-dogged lives. The elder was a religious controversialist who received manuscript-research commissions. The younger was essentially a manuscript hunter and dealer who was sacked at age 50 and had his "private" manuscript collection (which did not of course include the Pliny palimpsest) seized by the government from his Karlsruhe home in 1886.

Similar discoveries during the 21st century of miraculously surviving manuscripts of lost or semi-lost Latin or Greek works of Antiquity are likely to be the rarest events. The archives of Europe and the Middle East have been scoured so many times by so many generations of scholars that the pickings are now slim.

More likely is the reconnection of unlabelled manuscripts to their Antique authors, such as the discovery a year ago that an anonymous Greek-script manuscript in Munich contains Origen's Homilies on the Psalms, or my own proof that the "medieval" graphic genealogies in Spanish bibles are in fact a 5th-century Latin work.

I mentioned in a previous post that Martin Wallraff's paper revealing his attribution of a section of an Oxford manuscript to Eusebius would soon appear in print. The article will lay bare an Antique work, the Canon Tables of the Psalms, which no one had known about for the past 1,000 years. Professor Wallraff made his remarkable discovery public at the Oxford Patristics Conference in 2011.

Harvard University Press has now announced a publication date for this editio princeps. It will appear as an article in the next issue of the Dumbarton Oaks Papers. This ground-breaking paper will be available from December 16 this year and will be entitled "The Canon Tables of the Psalms: An Unknown Work of Eusebius of Caesarea", the announcement says. Presumably it will be on open access from 2024 under the periodical's web release policy.

2013-02-22

Studia Patristica

Over the past year, Professor Vinzent has edited hundreds of conference papers to create something the size of a major encyclopaedia. This enormous thing will emerge as volumes 53 to 72 of Studia Patristica, a journal that commenced in 1957. The fact that the cumulative run of a journal can increase by 38 per cent as a result of a single conference is alarming confirmation of the fear that we now entering an age when writers may soon outnumber readers. All of this excellent research will no doubt vanish into the shelves of research libraries and will be summoned by the occasional (wealthy) researcher from Peeters Publishers' full-text database, but how many of the articles will achieve a total global readership of even ten or twenty or thirty? A sobering thought.

My own paper, "The Great Stemma: a Late Antique Diagrammatic Chronicle of Pre-Christian Time", will appear in the Historica volume alongside papers by four eminent historians which I found among the most interesting of the entire conference:

- Guy Stroumsa's "Jerusalem, Israel, Athens, Jerusalem and Mecca: The Patristic Crucible of the Abrahamic Religions," which was a provocative exploration of how Islam, Judaism and Christianity are equal heirs of Late Antique intellectual debates;

- Josef Lössl's "Memory as History? Patristic Perspectives," which was a justification of his revisionist approach in his new textbook, The Early Church;

- Hervé Inglebert's "La formation des élites chrétiennes d’Augustin à Cassiodore," which told the interesting story of advanced education from the fourth century;

- Pauline Allen's "Prolegomena to a Study of the Letter-Bearer in Christian Antiquity," which lays the groundwork for an interesting book she is writing about Late Antique travellers who deliver letters.

It would appear that Martin Wallraff's discovery that Eusebius of Caesarea wrote another, previously unnoticed set of canon tables, which he made public at the 2011 conference, will not be written up in Studia Patristica, but in the Dumbarton Oaks Papers. The reason, I believe, is that this annual US journal is able to include high-quality colour reproductions of the new-found tables. Presumably that journal's moving firewall will allow the Wallraff paper to be downloaded for free from the year 2023.

2011-11-20

Rufinus

It has taken me some time to study the Lesser Stemma more closely. One of the critical questions in the course of this analysis was where its editor had obtained his textual commentary from. The final page, 8v, contains the familiar Great Stemma statement:

Sicut Lucas evangelista per Nathan ad Mariam originem ducit, ita et Matheus ev(an)glista per Salomonem ad Ioseph originem demonstrat. Id est de tribu Iuda, ut appareat eos de una tribu exire, et sic ad Christum secundum carnem pervenire. Ut compleatur quod scriptum est: "Ecce vicit leo de tribu Iuda radix David," leo ex Salomone, radix ex Nathan.But in a radical reversal of meaning, the Lesser Stemma bolts on to this a core statement from Julius Africanus. The following is my transcription of this from the Burgos Bible (the layout of the pages is tabulated on my website):

Ut clarius fiat, quod dicitur: ipsarum generationum consequentias enarravimus.

A David generatio per Salomonem, quam dinumerat Matheus, tercium a fine facit Mathan, qui dicitur genuisse Iacob patrem Ioseph. Per Nathan vero Lucas generationum ordinem texens, tercium nichilominus eiusdem loci facit Melchi. Nobis imminet ostendere, quomodo Ioseph dicitur secundum Matheum quidem patrem habuisse Iacob, qui inducitur per Salomone: secundum Lucham vero Heli qui ducitur per Nathan, atque ipsi, id est Heli et Iacob, qui erant duo fratres, habentes alius quidem Mathan, alius quidem Melchi patres ex diverso genere venientes, etiam ipsi Ioseph avi esse videantur.

Est ergo modus Mathan et Melchi de una eadem que uxore Hesta nomine diversis temporibus singulos filios procrearunt, quia Mathan, qui per Salomonem descendit, uxorem eam primus acceperat et relicto uno filio Iacob nomine defunctus est. Post cuius obitum, Me[l]chi qui Nathan genus ducit. cum esset ex eadem tribu, ex eadem tribu[sic], relictam Mathan accepit uxorem ex qua et ipse suscepit filium nomine Heli per quod ex diverso patrum genere efficiuntur Iacob et Heli iterini fratres quorum alter, id est Iacob, fratris Heli sine liberis defuncti uxorem ex mandato legis accipiens genuit Ioseph natura quidem germinis suum filium, propter quod scribitur Iacob autem genuit Ioseph: secundum legis vero praeceptum Heli efficitur filius, cuius lacob qui erat filius Mathan uxorem ad suscitandum fratris semen acceperat et per hoc rata invenitur atque integra generatio et tan, quam Matheus enumerat, et tan, quam Lucas competenti [?]ione designat.

I soon found that the above Latin text comes from one of the early translations of the Letter to Aristides. This was produced in the early years of the 5th century (perhaps 402 or 403) by Rufinus of Aquileia (see Christophe Guignard, La Lettre de Julius Africanus à Aristide sur la Généalogie du Christ, 2011, p. 24 ff. for a discussion). With a good text of Rufinus (the passage is numbered 1.7.5-11), I was also able to unlock most of the manuscript abbreviations and correct my transcription at places where I had not initially been able to make out the script.

Here is George Salmon's translation of the same passage of Africanus, which has been put into first-person speech though this is not necessarily required by the Africanus text:

But in order that what I have said may be made evident, I shall explain the interchange of the generations. If we reckon the generations from David through Solomon, Matthan is found to be the third from the end, who begat Jacob the father of Joseph. But if, with Luke, we reckon them from Nathan the son of David, in like manner the third from the end is Melchi, whose son was Heli the father of Joseph. For Joseph was the son of Heli, the son of Melchi. As Joseph, therefore, is the object proposed to us, we have to show how it is that each is represented as his father, both Jacob as descending from Solomon, and Heli as descending from Nathan: first, how these two, Jacob and Heli, were brothers; and then also how the fathers of these, Matthan and Melchi, being of different families, are shown to be the grandfathers of Joseph. Well, then, Matthan and Melchi, having taken the same woman to wife in succession, begat children who were uterine brothers, as the law did not prevent a widow, whether such by divorce or by the death of her husband, from marrying another. By Estha, then—for such is her name according to tradition—Matthan first, the descendant of Solomon, begets Jacob; and on Matthan’s death, Melchi, who traces his descent back to Nathan, being of the same tribe but of another family, having married her, as has been already said, had a son Heli. Thus, then, we shall find Jacob and Heli uterine brothers, though of different families. And of these, the one Jacob having taken the wife of his brother Heli, who died childless, begat by her the third, Joseph—his son by nature and by account. Whence also it is written, “And Jacob begat Joseph.” But according to law he was the son of Heli, for Jacob his brother raised up seed to him. Wherefore also the genealogy deduced through him will not be made void, which the Evangelist Matthew in his enumeration gives thus: “And Jacob begat Joseph.” But Luke, on the other hand, says, “Who was the son, as was supposed (for this, too, he adds), of Joseph ..."The Letter to Aristides was transported to the West as part of Rufinus's Latin translation of the Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius of Caesarea. Plainly this explanation of the gospel contradiction was popular and formerly in wide circulation. Mommsen discovered 90 extant manuscripts of this work of Rufinus in the late 19th century, according to Dr Guignard.

If the passage was already in current use in the 5th century, it would not be surprising that a partisan should have taken it up and used it to modify the Great Stemma to bring it into harmony with the contentions of Africanus, Eusebius and Rufinus, and at the same time to repel the Joachim theory, which is based on an apocryphal text, the Protevangelium of James.

The Lesser Stemma is however not completely faithful to Africanus, who omits two names (Matthat and Levi) between Joseph's father Heli and the more senior Melchi. At least as present in the Burgos Bible, the Lesser Stemma restores these names, but it does so in a non-orthodox order: it muddles the order of Melchi-Levi-Matthat and presents this as Levi-Macham-Melchi.

The greatest oddity of this text is that it contradicts the drawing alongside it. In the Burgos Bible, both genealogies clearly terminate at Joseph. In the image at right, the upper roundel (Joseph filius Iacob qui desponsavit Mariam) is the terminus of the Matthaean genealogy, and the lower roundel (Joseph sponsus Marie de qua natus est Christus) is the terminus of the Lucan genealogy. Yet the text retains the notion from the Great Stemma that the Lucan genealogy should end at Mary. This is an odd situation; I cannot at present see any coherent explanation for it.

2011-07-08

Oxford Patristics Conference

2011-05-28

E-Codices

Cod. Sang. 133 in the Abbey Library at St. Gall in Switzerland is an important source in understanding the antique book trade, since it contains a set of more or less intact stichometric lists. These were computations of the length of books, calibrated in στιχοι or stichoi, that were used to set both the cost of transcription (the scribe's wages) and the book price (what the bookseller charged).

Cod. Sang. 133 contain fourth-century measurements of the books of the Bible and the 28 works of Cyprian. We know from the writer Galen (quoted here by Diels) that a Greek stichos or unit was 16 syllables, and this source confirms a Roman stichos, or verse, was similarly 16 Latin syllables.

Once described by Bernhard Bischoff as the "oldest document of the Christian book trade" and used by scholars such as Bruce Metzger to estimate the bulk of early bibles, this record gives us an insight into the economics of book publishing. The content is of course dry, for example:

This translates as:

The Four Gospels:

Matthew, 2700 lines

John, 1800 lines

Mark, 1700 lines

Luke, 3300 lines

All the lines make 10,000 lines.

But there are some interesting observations. The author lets fly for example at exploitative Roman booksellers for their slack and cheating ways with his beloved Cyprian:

Because the index of verses in Rome is not clearly given, and because in other places too, as a result of greed, they do not preserve it in full, I have gone through the books one by one, counting sixteen syllables per line, and have appended to each book the number of Virgilian hexameters it contains (Rouse translation).

The St. Gall manuscript, written during the late 8th or early 9th century, probably at St. Gall itself, and another manuscript, Rome, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Vittorio Emanuele II, Vitt. Em. 1325 (handwritten catalog entry in Italian here, formerly Cheltenham or Phillipps 12266), written at Nonantola in the 10th or early 11th century, are the key practical records we have about the stichometric method.

These North African lists, the so-called indicula, were discovered (it seems) by the great Theodor Mommsen, who wrote them up in 1886. Mommsen expanded his fame with this codex in the late 19th century, publishing the Liber Genealogus in his MGH series. It also contains a curious work, the Inventiones Nominum, which mentions a good many unusual biblical names that never made it into canonical scripture.

The St. Gall codex was revisited in 2000 by eminent US professor Richard Rouse, who argued that the 11 items discovered by Mommsen in the collection (see below) were not a random group of texts, but formed an intact North African reference book or compendium. It had travelled through the centuries together and had been put together by Donatist scholars, according to Rouse and his co-writer Charles McNelis.

The St Gall codex is of quite a small format, which explains why the Liber Genealogus, not a very long work, fills 49 of its folios: there is not that much writing on each side. The script is very clear and the parchment clean, which suggests it was probably not very heavily used in its day. This text of the Liber is the earliest recension (the direct description of the Great Stemma) and therefore the most important.

Here is Mommsen's Latin description of the compendium, interspersed with text from Scherrer's 1875 St. Gall printed catalog, with one or two additions by me (the English bits, obviously):

Cod. Sang. 133

Pgm. 8° s. VIII u. IX; 657 (656) pages.

Scherrer: Drei oder vier Handschriften in einem Band. [Preceded by Eusebius/Jerome on Holy Land place-names. Followed by Isidore Chronicon pp 523-590 and 'Incipit cuius supra Goti de Magog Jafet filio orti' pp 590-597. Pages 598-601 blank.]

Mommsen: saec . IX formae octonariae praeter alia quae recenset catalogus editus p. 48 [Scherrer] a glutinatore demum cum his compacta medio loco p. 299-597 continet commentaries qui sequuntur:

1. p. 299 – 396 librum genealogum infra editum. [Scherrer: S. 299-396: 'Inc. liber genera(tio)num vel nominum patrum vel filiorum vet. test. vel novi a s. Hieronimo prbo conpraehensum etc. Incipit genilocus sci Hieronimi prb.' Am Ende: 'Explicit liber genealogus.' (Unbekannt und nicht von Hieronymus; reicht, laut p. 396, bis zum Jahr der Welt 5879 oder bis zum Consulat 'hieri et ardabii.')]

2. p. 397 – 420 incipiunt prophetiae ex omnibus libris collecte. quae prophetiae membra habent .... cecidisse in hanc voluntate perseverantes caeci a dei fide lapsi sunt ignorantes. expl . coll . prophet . veteris novique testamenti. [Scherrer: S. 397-426: 'Incip. prophetiae ex omnibus libris collecte.' (Katechese).]

3. p. 420′– 421 incipiunt virtutes Haeliae quae eius merito a domino factae sunt. prima virtus. clausit caelum . . . sublatus est in caelo.

4. p. 421 – 426 incipiunt etiam Helisei virtutes. prima virtus. de melote divisa est .... post mortem suam revixit. expl.

5. p. 427 – 454′ inc̅p̅t̅ inventi̅o̅n̅ nomi̅n̅ , duo sunt Adam , unus est protoplaustus .... et alius est Domires vir sponsor Teclae: inter ambas autem sunt an̅n̅ ferme DCCLXX. [Scherrer: S. 427-492: 'Incipt. invention. nominum.' (Aufzählung von Personen- und Völkernamen des A. T.).]

6. 454′– 484′ sequitur liber generationis cum praescriptione hac: haec sunt diutissime . . . . . . anni sunt v̅dccccxviii (vide infra p . 89), sed c . 240 – 331 ad brevem epitomam redactis et ad eius finem inserta computatione quae statim referetur adsunt rursus nostrae editionis c. 333 – 361, abest pars extrema c . 361 – 398: subscriptum expl .

7. p. 484 – 485 item interpretationes filiorum Iacob de Hebreo in Latino. amen vere. Ruben dei spiritus cet.

8. p. 485 – 488 item interpretationes Hebreas in Latin translatas . Hebrea lingua triplex .

9. p. 488 – 492 incipit indiculum veteris testamenti , item novi et Caecili Cipriani, quos indices versum numerum per singulos libros enuntiantes ex gemello libro Cheltenhamensi edidi in Hermae volumine 21 p . 142 seq. librarius iam is qui archetypum scripsit indices eos ad librum generationis non pertinentes neque ei continuatos ad titulorum eius laterculum adiunxit (v. p. 89 not.).

10. p. 492 item interpretationes Hebreas in Latinum . Maria domina cet. [Scherrer: S. 492-522: 'Interpretationes hebreas in latinum etc. Nomina locorum et interpr. nominum de hebreo in latinum. (Excerpte aus Hieron. Liber de interpr. nom. hebr. Opp. ed. Mart. II, von p. 3 bis circa p. 83.)

11. p. 493 – 522 nomina locorum et interpretatio nominum de Hebreo in Latinum. Hermon regio Hebreorum cet. similesque interpretationes aliae.

There is a very old Wikipedia article on stichometry, which I have just fixed a bit. Not just old in the sense of posted in 2005, but old because it was copied from a 100-year-old Encyclopaedia Britannica: it stated that one of the codices is at Cheltenham in Sir Thomas Phillipps's collection. In fact that collection was broken up and sold a century ago. This codex was purchased by the Italian state, and I have altered the Wikipedia article accordingly.