On March 4, 2015, the digital library of the BAV or Vatican Library placed online nearly 100 newly digitized manuscript codices and map folders.

As is usual, there was no public announcement of this. I have no contact with Rome, so I can only speculate as to the reasons for such a silence. It may be that the library's server has a limited capacity and could not cope with the acute surge of requests that would follow any publicity.

Or there may be no funding to conduct public relations for a project that is being mainly funded by corporate and private sponsorship. It is possible too that funding institutions such as the Polonsky Foundation, which has a key role in digitizing the Hebrew manuscripts, wish to make their own public presentations at a later date. Polonsky announced February 24 it had reached the 1-million page mark.

But perhaps there is simply a modest sense at the BAV that this is no big deal yet, given that the project started years ago and the intermediate goal of getting 3,000 manuscripts online may not be met until 2016 at this rate. To get the entire stock of 82,000 BAV manuscripts digitized may take four decades, and at the same time, the BAV has committed to separately digitizing thousands of incunables. (See the presentation of one of the world's oldest printed cookbooks.)

Nevertheless the release is quite remarkable.

Less than a year ago, the manuscripts site consisted only of clones of independent digitizations by the Heidelberg state library in Germany and a paltry 24 Roman manuscripts, as I noted at the time. Today the BAV site offers a total of 1,787 works and has surpassed the tally of digitized manuscripts offered online by the British Library (1,220 at the last tally) or by e-codices of Switzerland (1,233).

Of the 151 collections making up the Rome library (see the BAV’s own list), 50 are now represented in some way in this digital presence.

Using comparison software, I have identified the following 97 newcomers this week. I have added notes on content, which are in some cases guesses more than anything else.

- Barb.gr.6, Maximus Confessor, 580-662, Opere spurie e dubbie

- Barb.gr.372, Psalter

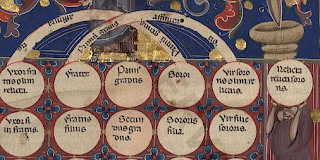

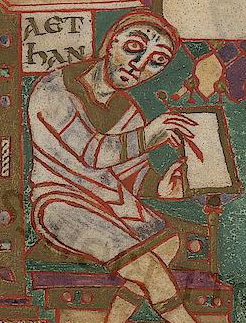

- Barb.lat.2724, Chronicon Vulturnense: Miniatures, most of them showing the handing over of donation charters to St. Vincent, like Bishop John's This extraordinary compilation was made about 1130 and tells the history of the monastery at Volturno, Italy (Wikipedia). A monk of the monastery, Iohannes, composed the Chronicle.

- Barb.lat.4076, is an autograph of Francesco da Barberino's Renaissance poem, Documenti d'Amore. Here is a cartoon-style blurred action image showing some impressive rapid-fire archery in all directions:

- Barb.lat.4077, More Francesco da Barberino

- Barb.lat.4391.pt.B, maps of Roman fortifications in 1540

- Barb.lat.4408, working drawings for mural restorations in 1637

- Borg.gr.6

- Borg.isl.1

- Borg.lat.420, Coronation of Clement VII

- Borg.lat.561, Life of Roderico Borgia

- Borgh.2, texts of Leontius and of Ephraem the Syrian

- Borgh.4, Gregory the Great: Moralia in Job

- Borgh.6, collected sermons

- Borgh.7, Pope Boniface, Decretales

- Borgh.9, Porphyry of Tyre and Boethius

- Borgh.10, Letters of Seneca

- Borgh.11, Order of Consecration

- Borgh.12, Works of Godefridus Tranensis

- Borgh.13, Works of Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā Rāzī, 865?-925?

- Borgh.17, Henry of Ghent’s Summa

- Borgh.18, Boethius

- Borgh.19

- Borgh.20

- Borgh.23, Italian sermons

- Borgh.24

- Borgh.25, Vulgate bible

- Borgh.26, 13th-century legal text, Apparatus Decretorum

- Borgh.27, Gerardus de Bononiensi

- Borgh.29, Wyclif?

- Borgh.30

- Borgh.131, Boethius, Variorum

- Borgh.174, 14th century sermons

- Borgh.372, Glossa on Justinian. Here's a miscreant in blue hauled into court on 147r

- Borgh.374: A 13th-century text of the Emperor Justinian's legal codifications including the Institutions, annotated by medieval lawyers. Justinian was emperor at Constantinople 527-565. Here's a widow under the heavy burden of a no-incest provision in Borgh 374 at 4r:

- Borg.Carte.naut.III.

This is Diogo Ribeiro's 1529 map "in which is contained all that has been discovered in the world until now." Less than four decades after Columbus’s first voyage across the Atlantic, it shows the Americas in detail, but not New Zealand, which the Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman was not to document until l642 and which James Cook was not to circumnavigate and map until 240 years after this map was drawn. Jerry Brotton's History of the World in Twelve Maps features it.

Unfortunately the resolution of this digitization, welcome as it is, falls short of what one would hope for. The section above is the Gulf of Mexico, and it is impossible to zoom in far enough to read the place-names. I would presume the map has been scanned at much higher resolution, and I hope @DigitaVaticana can upload this so that the fourth and closest zoom level provides legible text. - Chig.B.VII.110

- Chig.C.VII.213

- Chig.C.VIII.228

- Chig.P.VII.10.pt.A

- Ferr.30, letters of Giuliano Ettorre

- Ott.gr.314

- Ott.lat.1050.pt.1

- Ott.lat.1050.pt.2

- Ott.lat.1447

- Ott.lat.1448

- Ott.lat.1458, Ovid’s Metamorphoses

- Ott.lat.1519

- Pal.gr.55

- Pal.gr.135

- Reg.gr.80

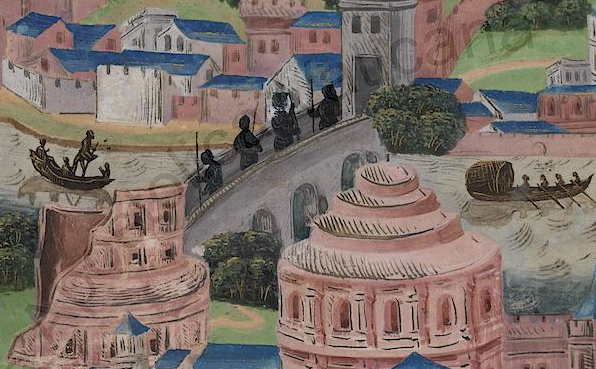

- Reg.lat.88, French chronicle

- Reg.lat.695, Life of St. Denis

- Reg.lat.720

- Reg.lat.721

- Reg.lat.1480, Ovid in French, illuminated.

Here's one of the fine pictures (folio 156r). I think it is Diana about to sock it to Actaeon, who will be trying desperately to explain that he is not a stag. With those feeble arms, she really ought to spend less time at home curled up on the couch and more time at the gym:

- Ross.61

- Ross.70

- Ross.74

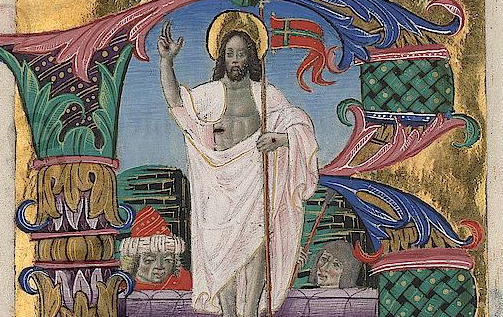

- Ross.181, Missal from St Peter's Monastery, Erfurt, Germany, datable to about 1200: see the post on this by Klaus Graf (reproduced below as comment) with a search that points to comparable missals in German archives and the influence of Conrad of Hirsau, a Benedictine author, on the German scriptoria.

- Ross.186, Gilbert of Hoyland

- Ross.198

- Ross.206, Psalter

- Ross.292

- Ross.553, Hebrew Ms.

- Ross.554, illuminated Hebrew Bible

- Ross.556, Hebrew Psalter

- Ross.733

- Ross.817, Gilles Bellemère

- Urb.ebr.2, Kennicott-Rossi 225 according to @RickBrannan

- Urb.ebr.4

- Urb.ebr.5

- Urb.ebr.6

- Urb.ebr.7

- Urb.ebr.8

- Urb.ebr.10

- Urb.ebr.11

- Urb.ebr.12

- Urb.ebr.14

- Urb.ebr.15

- Urb.ebr.17

- Urb.ebr.18

- Urb.ebr.19

- Urb.ebr.21

- Urb.ebr.22

- Urb.ebr.23

- Urb.ebr.24

- Urb.ebr.26

- Urb.ebr.28

- Urb.ebr.29

- Urb.ebr.30

- Urb.ebr.31

- Urb.ebr.37

- Urb.ebr.38

- Urb.ebr.39

- Urb.ebr.40

- Vat.ebr.71, Ḳimḥi, David ben Yosef, c.1160-c.1235, Commentary on Latter Prophets

Follow me on Twitter (@JBPiggin) for more news of these digitizations. [This is Piggin's Unofficial List 4.]