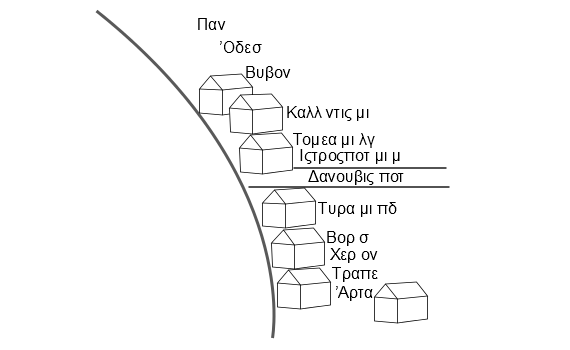

After searching for some time for any ancient board game on which the Great Stemma might possibly be modelled, I believe the best match would be an Egyptian-devised game-board with 58 holes which has some similarities with our snakes and ladders. Here is a schematic of the game-board, based on a 1952 drawing by Harold Murray in his

History of Board Games Other than Chess.

While this is neutrally known among scholars as the Game of Fifty-Eight Holes, in a 2000 article (all references below), Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi notes that archaeologists have often called the game Hounds and Jackals. She proposes her own name for the game, the Monkey Race. According to William Hallo, this game, apparently played with dice, has more than 4,000 years of history.

Such boards are first attested in IXth Dynasty Egypt (ca. 2100 B.C.) and there and in Palestine are made of wood or ivory, elsewhere of stone or clay. Examples of the latter are known from Ras el Ayin and Tell Ajlun in Syria, from Mesopotamia, and from Susa in Elam. Some examples even come from the palace of Esarhaddon and bear his royal inscription. They date from all periods; indeed, their modern counterparts are in use in the Near East to this day. (Hallo, 1996, p. 114)

Hallo does not say who plays the game in modern times, and I can find no one else who claims this to be so. Indeed, the precise rules of the advanced games (one assumes there were many variations) seem to be now lost, and the presentation of the archaeological record suggests the game may have vanished by Roman times.

It is notable that all the boards recovered are much smaller than we would employ for a table-top board game nowadays. In size they are closer to a smartphone or a small tablet computer. For images, one should consult the

Louvre website where exquisite variations are assembled into a very impressive interactive page, the best I have found on the internet.

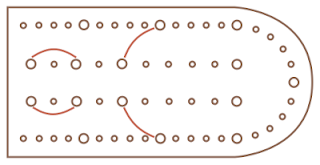

There is a

deluxe version of the game (linked picture above) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Despite appearances, it is not a billiard table, but a tiny toy just 15 centimetres long. The stakes in the picture are the counters, five per player, used during play. The Met has six high-resolution photos where you can zoom in for a closer look.This Egyptian grave offering from Thebes explains the order of play through the 29 holes by each player as follows:

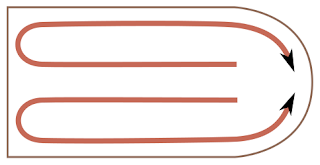

The final curves, converging after running along the perimeter, do bear a remarkable resemblance to the closing stages of the

fila as they converge on the right side of the Great Stemma, or of the

Amiata Stemma (below). I rotated Murray's drawing (above) 180 degrees so you could see this resemblance more plainly.

I have always considered the diagram's circle-by-circle progress to be inspired by a board game rather than by a topological map. Human problem solving and inventiveness is often a matter of transferring some old and familiar method into a new context, then elaborating this new technique by a cumulative process.

I do not suggest that the Great Stemma

copies or

evokes the 58-hole board game, but simply that the game, which is said to have been played in an altered version among the Copts of Egypt in Late Antiquity (see an

image of the Louvre's Coptic variation),

might have been the germ that set off a bright idea in the 5th century.

Richard S. Ellis and Briggs Buchanan provide a detailed scholarly discussion of such 58-hole boards. They group them by outline (the commonest are shaped like an axe-head or fish) and offer many line drawings in their 1966 article dedicated to a single artefact,

An Old Babylonian Gameboard with Sculptured Decoration, in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies (

JSTOR). For older materials, see French archaeologist Roland de Mecquenem's 1905

report,

Offrandes de fondation du Temple de Chouchinak, where there are line drawings of several tiny boards from Iran, generally carved from limestone and less than 10 centimetres long. That report is online at Archive.org. See also

Iranica Online. Various enthusiast links on the topic have been collected by

Alain Tilmant.

Dunn-Vaturi, whose 2000 bibliography should be consulted, is one of the authors of a current

article,

Cultural transmission in the ancient Near East: twenty squares and fifty-eight holes (citation below). It includes the above maps, which I am also linking to with Blogger (without copying) so that you can see them. The left map suggests how the game is likely to have spread out from Egypt: the other map deals with the "royal game of Ur", a similarly popular 20-square board game.

Also available: a February 2012 lecture by Dunn-Vaturi on

video (in English), where she suggests (at 1:20) that a Babylonian form of the game board may also have symbolized the human body, and quotes the theories of

Carl Schuster that the joints on such a "rebirth" symbol may have been used as a palaeolithic mnemonic system to construct genealogies. The game of 58 holes is among those currently on display at the

Musée de Cluny in Paris until March 4. See also Dunn-Vaturi's notice about the game at the

Louvre and a November 2012 radio

interview (in French).

Dunn-Vaturi, Anne-Elizabeth. ‘“The Monkey Race” – Remarks on Board Games Accessories’. Board Game Studies, no. 3 (2000). http://www.boardgamestudies.info/pdf/issue3/BGS3Vaturi.pdf.

Ellis, Richard S., and Briggs Buchanan. ‘An old Babylonian gameboard with sculptured decoration’. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 25, no. 3 (July 1966): 192–201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/543265.

Hallo, William W. ‘Games’. In Origins: The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Brill, 1996.

Mecquenem, Roland de. ‘Offrandes de fondation du Temple de Chouchinak’. Mémoires de la Mission Archéologique de Perse 7 (1905): 61–130. http://archive.org/stream/mmoires07franuoft#page/104/mode/2up.

De Voogt, Alex, Anne-Elizabeth Dunn-Vaturi, and Jelmer W. Eerkens. ‘Cultural transmission in the ancient Near East: twenty squares and fifty-eight holes’. Journal of Archaeological Science 40, no. 4 (April 2013): 1715–1730. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440312004955.