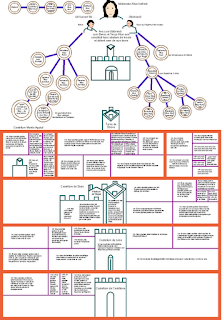

I have created a digital sketch of the document (PNG below, zoomable detailed version on my website). The colours were arbitrarily chosen, since this version was made from black and white photographs. For a better idea of how Hildebrand and his two sons, Berizo and Teuzo, are supposed to have looked, see the original (link below, with caveat). The orange-bordered panels represent the ownership shares in six blocks of property:

- the Castellum Montis Agutuli

- the Turris de Strove (Strove is the next village)

- the Villa de Scarna (just to the west)

- the Castellum de Staia (the small town of Staggia to the north (map))

- the Castellum de Leke (further north, at Lecchi (map))

- the Castellem de Castillione

Hildebrand (Ildibrandus) was a Lombard, which explains the Germanic names of his ancestors and his descendants all the way through the document. The six semi-monastic properties (five of which are illustrated with a little sketch that probably summed up salient architectural features of the principal building) were progressively divided into half-shares, quarters and so on. The most extreme divisions are 1/32 of a whole. The rectangle area indicates the degree of division. The transcription is based on that published by the late Wilhelm Kurze, and I have preserved his fractions where space allows. There are of course no Arabic numbers or fractions on the document, but including them here makes the divisions more understandable.

The affinity of the stemma at the top of the document to the Great Stemma is unmistakeable: the roundels are all composed of two rings, and the names in them are generally written in the form Y filius X. The lines can either proceed left to right or top to bottom. An especially interesting feature here is the graphic separation of Adelheid, wife of Ugolinus, and of Sindiza, wife of Berizellus, from the rest of the stemma. They are not joined to it by the usual lines. The children of their second marriages were not connected by blood to Hildebrand, but did inherit property rights through the mothers. I have moved these into better alignment to make this aspect of the infographic clearer, but this reconstruction is as close as possible to the original in every other way.

Kurze gives the following manuscript reference: S. Eugenio - Rome, Bibl. Vat. Cod. Vat. Lat. 8052 (Galetti) Cop. saec. XVIII. In dorso: Descriptio et pictura fundatorum abbatie Insule et eorum descendentium que predia relinquerunt predicte Abbatie.

As far as I know, there is only one image of it online, on the Portale di Archeologia Medievale, but this is something of a disappointment. This image seems to have been digitally altered: not only are important areas at the edges cropped away, but the top three property blocks have been seamlessly edited out of the middle of it, without any explanation. (If you find a more faithful image of the document on the web, particularly one at higher resolution, please tell me by writing a comment below!)

Kurze mentions one facsimile edition. The document is reproduced in low-resolution black and white in Violante's article and at an even smaller scale in Klapisch-Zuber's book. In my view, text-only publications cannot adequately convey how the infographic works: a technical drawing is needed. Violante's crude sketch only adds to the confusion and from Klapisch-Zuber's account I mistakenly thought at first that a kind of treemap was in prospect. The property-division part of the infographic, which maps the legal concept of sharing onto two-dimensional space, is in fact a much simpler concept, but nevertheless quite clever. I do not know of any earlier documentary examples of the technique. Please comment if you can suggest any.

This is the only medieval document I have transcribed so far where the place of origin is absolutely clear. The monastic institution where this document was drawn up after 1160 no longer exists, but many of the buildings are still there and can be visited, a short drive away from Siena (tourist description, location, video). The structure depicted at the top of the chart, below Hildebrand's face, is the abbey itself, which was much rebuilt but partly survives. The castle of Staggia has a battlemented tower just like those in the document. I recommend you follow these links and enjoy the images which Google Panoramio pulls up.

Kurze, Wilhelm. “Der Adel und das Kloster San Salvatore all’Isola im 11. und 12. Jahrhundert.” Quellen und Forschungen aus Italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken 47 (1967): 446–573.

Violante, Cinzio. “Quelques Caractéristiques des Structures Familiales en Lombardie, Émilie et Toscane aux XIe et XIIe Siècles.” In Famille et Parenté dans l’occident médiéval, edited by Georges Duby and Jacques Le Goff, 87–148. Rome: École Française de Rome, 1977.

Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane. L’Ombre des Ancêtres. Paris: Fayard, 2000: 98-101.

Cammarosano, Paolo. “Gli Antenato di Paolo Diacono.” In Nobiltà e chiese nel medieoevo e altri saggi. Scritti in onore di Gerd D. Tellenbach, edited by Cinzio Violante, 37-45. Rome, 1993.