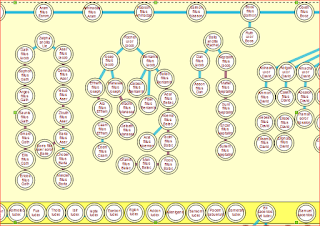

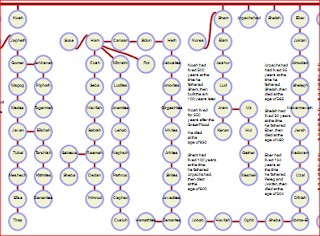

Things have been quiet on this blog and my Twitter stream because I have been working on a major project: a complete reconstruction of the oldest known conceptual infographic in the world: the fifth-century Latin Great Stemma.

When I first announced its rediscovery in 2011, I presented a rather freely drawn plot of it (see this in my article in Studia Patristica or archived on my website as an swf (Flash) file):

This time round, I am trying to do something much harder: to replicate the chart without any accommodations to modern assumptions, showing it precisely as it was intended by its designer.

The result (link) is the layout that the designer would have saved if the SVG mark-up language had existed in the fifth century. Not only are the lines, circles and text in the precise locations where the design called for them to be positioned. These positions also allow us to observe the design's hidden concepts and rules. This new drawing is not an impression of the late antique original: it is an encoding of the design itself.

The starting point for my revision was wise counsel from a great infographics teacher and practitioner, Raimar Heber of Germany. Raimar has just published a textbook (in German, Rheinwerk Verlag) of best practices in infographics and it looks very good indeed from the page samples.

In 2011, Raimar offered to do a retro-engineering experiment: he world accept an imaginary design brief and visualize the data of the Great Stemma as one of the world's leading professional art editors would design it today. He drew up a graphic sampler. One frame of it pitched a grid as the basis of the visualization. Chains should be laid out in the horizontal and vertical, he argued, with shoots allowed at 45-degree angles if the going got tough.

For a long time, I was sceptical about this. It sounded too 21st century to me. There is only one manuscript of the Great Stemma where straight lines and right angles stand out (Plut 20.54 in Florence), but one tends to assume that was just the obsession of an over-neat scribe.

But in spring this year I began re-analysing every substructure of the Great Stemma using a selection of the best manuscripts. This involved no less than 30 separate investigations, listed here as a "detail views".

For the first time I noticed something.

The manuscripts contain many vertical columns of roundels (the circles containing names). If one counts how many members there are in such rows, one comes up unusually often with the number 10. There might for example be a column of eight connected roundels, in a place where two others above them block the area overhead. Or there are long chains which bend to the left or the right at the 10th member in many manuscripts.

So as an experiment I worked to trim all 100 of so columns of the Great

Stemma so that each was 10 elements high. If you array that many columns side by side

it naturally appears gridlike.

This alignment became a new paradigm. Not only is this pattern harmonious, but it also provides a simple and logical explanation for so many bulges, interlocks and elbows in the manuscripts. I am convinced it is the lost original pattern that the designer used. So Raimar's insight turned out to be spot on.

On reflection there would have been good reasons to use a grid. Firstly, it makes designs easier to read. That is an imperative of then and now.

Secondly, it makes a design much easier to hand-copy, which is no longer an imperative now, but was an important concern before the rise of printing. If you draw a grid where the written data expand neatly in two dimensions, and prescribe moreover that certain squares be left blank, you have a robust model for copyists to work from. We should study whether a similar method may have been used to copy the Peutinger Table, mappaemundi and other late antique charts by hand.

Take a look at my new reconstruction, which translates all of the 5th-century design into a (gridlike) pixel coordinate system. This design is not drawn by hand, but as output from a new database I have built, where all the crossing points in the grid have been recorded, along with the roundels, texts and connectors that pertain to those crossings. Other scholars may offer their own editions in future, but I would argue that the Piggin Stemma is the most accurate reconstruction on the available evidence.

A contemporary buzzword is digital humanities, which often is

simply watered down to mean storing and searching old documents as scans

in databases. True digital humanities work is something more: it means recasting historic creative work from its original analog expression

to a digital expression which remains absolutely congruent with the

artist's or writer's intentions, but yields more insight.

I have tried to make this chart even more accessible by translating its text

into English and by supplementing it with explanatory plaques and interactive

visual effects (look for radio buttons like those above). Tell me if it works like this and how you think it might be further improved.

Disgrace

18 minutes ago