Among its great oddities is a fishnet pattern among the descendants of Noah that largely obliterates the careful encoding of their relationships which was characteristic of the original model. That led Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, who is the greatest scholar to have surveyed the full history of such diagrams, to dismiss the whole class of Spanish Bible diagrams as an affront to the principles of ‘graphical semiology’. She argued in her 2000 book that no coherent biblical genealogical diagram had existed before a medieval work, the Compendium, was devised by Peter of Poitiers.

Her point of view was taken up and amplified soon after by Beate Kellner, who is now deputy principal of Munich's Ludwig Maximilians University (LMU), in her Habilitationsschrift, which was published in 2004. Kellner also focussed this part of her research solely on the Saint-Sever manuscript in Paris.

She seemed to be even more troubled by the way the diagram strung out siblings like beads on a string instead of exhibiting them in hierarchical fashion as we do in "family trees", and spotted another oddity of the Saint-Sever manuscript, its curious folding together of the descendants of Leah:

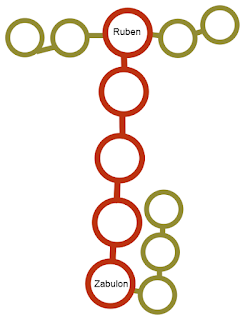

Here the organization of the panels avoids a coherent reading order as we would conceive it, from the top to bottom or from the bottom to top ... The genealogy below Jacob and Leah begins with their son Reuben ... His brothers Simeon, Levi, Issachar and Zebulun follow in a series of roundels which is open to interpretation as a genealogical line of descent since the line is graphically vertical, although in fact it links persons of a single generation. The sons of Zebulun are similarly connected by lines to one another in the vertical, and with their father, in such a way that the arrangement is effectively an ascending one. (JBP translation, hover for German original)The sketch below shows the situation referred to, with the remainder of the environs omitted, and it must be agreed that the Saint-Sever artist took a very free attitude to his Vorlage when he arrayed Reuben's sons to both the left and right and ran Zebulon's sons up the page instead of downwards:

Now this is not the place to consider whether Kellner's overall characterization of medieval genealogy is correct or not. But the Saint-Sever treatment of the Great Stemma is so original and so untypical of its diagrammatic tradition (list of manuscripts here) that it can hardly be taken as representative of very much other than the artistic sensibility of Stephanus Garsia Placidus, the monk who seems to have been its creative director and principal artist. Yolanta Zaluska has pointed out odd inconsistencies in the diagram which suggest that something went wrong with the project and that someone other than the original director completed the diagram.

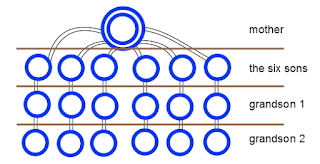

The classical arrangement of the sons of Leah in the Great Stemma is in fact severely regular, and it normally embraces all six sons, not five as in the Saint-Sever recension which omits Judah in this position. Here is a schematic of the same group from the Plutei manuscript, which contains pretty well the earliest format we can discover in the diagram's history:

Now it is true that the reading order of grandson 1, grandson 2 and so on is not the order that we in the 21st century could conceive as proper. But it does adhere to a broad logic in the Great Stemma where certain sibling groups which are only supplementary to the broad purpose of the document are always shown in space-saving fashion as vertical series. This is perhaps surprising to our eyes, but it is not chaos.

Following this generalization, Kellner then ventures the hypothesis that the crowded design of the Saint-Sever diagram deliberately establishes a stemmatic tangle, with extensions running every which way, in order to suggest that kinship by its very nature tends to be a network,

... that genealogy is being placed before us as a tapestry of relationships, as a complex structure oriented in multiple directions and not as a unitone line of descent... My hypothesis is that graphics, which are better able to exploit the two-dimensionality of the page, enable this particular form of discourse from the first glance, unlike a purely textual listing of genealogies, which certainly can employ linguistic features to link backwards or forwards and to that extend is capable of catering for genealogical cross-connections, but is ultimately bound by the continuity of script and creates an impression of linearity from the very character of text. (JBP translation, hover for German original)One already hears an ominous creaking in this structure of ideas, built as it is on evidence that simply does not support it. Rather than building on the august traditions of German text-critical scholarship, on the detailed analysis of the full range of manuscripts, such an interpretation employs the semiotics approach of Jacques Derrida, Roland Barthes and Co. which was popular in the late 20th century, spinning creative meaning and significance around supposed "signs", while paying too little attention to verifiable data about what one might describe as the ecology of culture - the structures of the human mind, the evolution of artefacts and the phenomenal experience of human societies.

Kellner is undoubtedly right in her observation that Saint-Sever often lacks diagrammatic coherency, but her analysis is based solely on a single, rather non-representative manuscript in Paris and a series of creative blunders when an artist outran his own talents in a single scriptorium in Gascony, leaving her vulnerable to a whole herd of counter-evidence from nearly 20 other manuscripts.

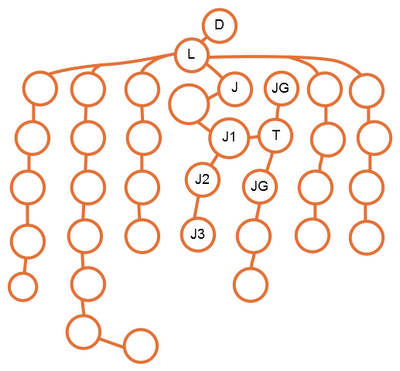

Older recensions of the Great Stemma are generally more coherent and rational in the way that they map family relationships to a consistent code using connections, alignments and orientiations.

Developing her point, Kellner correctly intuits that the genealogical diagram belongs in a tradition where the expansive roll was the more natural medium than the cramped codex page, but strays into even more unsupported territory with a suggestion that medieval historians felt a 2D visualization to be inherently freer than text in its choices of content and arrangement:

The notion of genealogy as a network of relationships could be conveyed graphically using relatively simple shapes such as lines, strips and circles on codex pages - or doubtless ideally in scroll format - because arrangements of the genealogical elements in planar space - and this is the key objective - were able to be selected and combined with greater freedom. (JBP translation, hover for German original)Here I both agree and disagree. Planar space is a far more comfortable medium to organize one's genealogical data and snippets of evidence than linear text. Sketching and diagamming often help us to organize our ideas and evidence better. Medieval diagrams do indeed breathe a certain air of nerdish delight at being able to amass the evidence to show some new view of it.

But diagrammatics are rarely a zone of freedom. Keller perhaps extrapolates from the freedom of art in comparison with the literary discipline prevailing over poetry and prose. But the overwhelming trend throughout the history of graphic charts and displays has been to bind them as tightly as possible to the habits of human spatial perception: without such discipline, diagrams simply fail to communicate.

Diagrammers who ignore "programming" principles are not breathing the air of freedom or expressing a view about the complexity of kinship relations and the intricacy of existence. When they discard a coherent system that has been handed down to them, they end up writing bad code. The Saint-Sever diagram is an experiment, probably by Stephanus himself, that went wrong.

Kellner, Beate. Ursprung und Kontinuität: Studien zum genealogischen Wissen im Mittelalter. W. Fink, 2004. Discusses the Great Stemma pp 50-53.

Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane. L’ombre des ancêtres. Paris: Fayard, 2000.

Zaluska, Yolanta. ‘Les Feuillets Liminaires’. In El Beato de Saint-Sever, Ms. Lat. 8878 de La Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris, edited by Xavier Barral i Altet. Madrid [Spain]: Edílan, 1984.