In some work, such as grammar texts, the brace could soon be taken as read and simply omitted, as in a 1533 printing in Basle, Switzerland of the grammar of Donatus edited by Heinrich Loriti or "Glarean". But the normal procedure was for the typesetter to make a brace for such layouts.

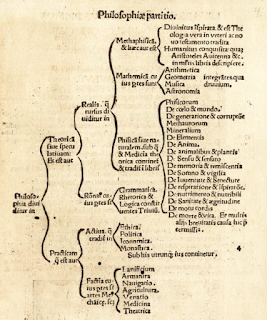

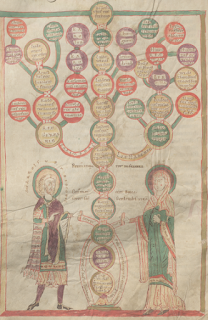

Where the material in the stemma was more copious, printers laid it out with its root at the top. In a 1540 Basle printing of Livy's Decades in the edition of Glarean, the brace is still hand-cut:

Printers soon recognized it was quicker to resort to their typecases, combining the small pieces of straight rule and rounded corners supplied by their typecutters to form braces.

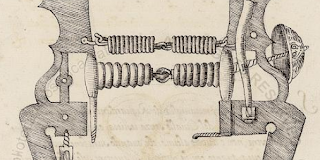

The first explicit explanation of this practice which I can find appears 200 years later in The Printer's Grammar by John Smith (link goes to a full edition of 1787, but the original seems to have come out 1755). It explains how a printer mainly resorts to his middle-length rules to do this:

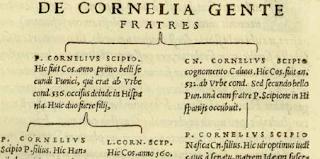

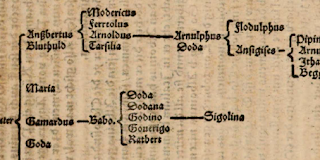

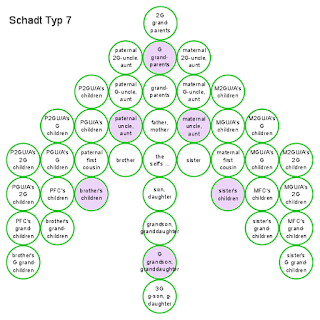

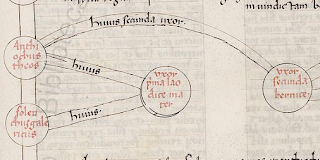

Middle and Corners are very convenient in Genealogical Work, where they are used the flat way; and where the directing point is not always in the middle, but has its place under the name of the Parent, whose offspring stands between Corner and Corner of the bracing side, in order of primogeniture.The "directing point" was a specially cut form to be found in the standard typesets in Basle. We see this in a 1557 example of a book by Wolfgang Lazius (1514-1565) (biography) in De gentium aliquot ... (online), page 589:

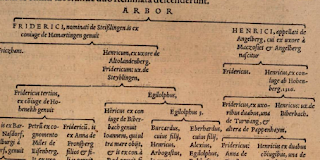

Elsewhere the point might be made from two corners, as in this 1556 book of genealogies (online) by Ernst Brotuff (1497-1565) (nasty biography) printed at Leipzig, Germany, where if one looks carefully, the joins between the rules are visible:

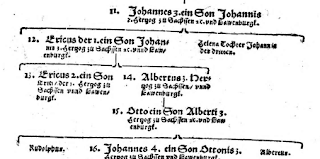

Sometimes the brace was reduced to a minimum as in a 1559 example. As another option, Johannes Herold (1514-1567), who was a publisher in Basle (biography), often preferred stemmata with the root at the left, as we see in his 1561 Churfürstliches Haus der Pfaltz an Rhein (online). Here too one can see that these braces were not hand cut, but assembled from smaller parts:

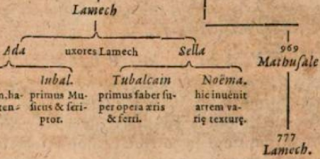

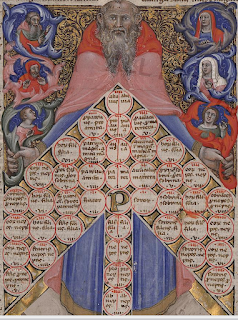

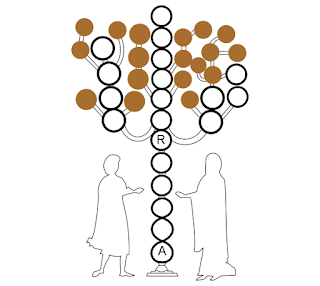

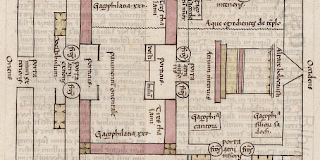

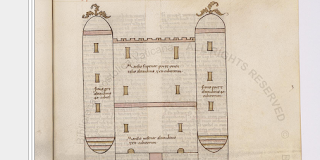

The curly brace was thus the printers' most important instrument in adapting the ancient graphic idea of the stemma to the technology of the printing press, where the need to square the forms that will be put into the type-bed presupposes that all elements fit together at 90-degree angles. When Leonhard Ostein of Basle came to print Hulderic Zwingli junior's edition of the Compendium of Petrus Pictaviensis in 1592 (previous blog post), he could hardly do otherwise:

Later tabular printing including some braces has been listed by an interesting Munich project, Historische Tabellenwerke (ended 2007), but I am not aware of any research on braced stemmata in incunables. What I am currently trying to do is take this history back beyond 1500. It is plain that the solutions then in use were not experimental, but settled practices. Can anyone help me find older examples?