Google Street View enables a virtual visit to the Abbadia San Salvatore at Monte Amiata, Italy which was mentioned a few months ago in this blog as the source of three outstanding medieval codices.

The abbey was suppressed in 1782 in consequence of a scandal involving Filippo Pieri, the last abbot, his brother who was also a monk and their live-in girl friend, who had become pregnant. The account, quoted by Michael Gorman, includes an outraged duke denouncing the monks for their "airy, careless, protected, ignorant, liberal" ways and the public scandal they sowed.

A religious community was re-established in 1939, but as far as I can see on the internet, it is no longer there. A municipal website for the town, which took over the name from the religious community, provides no further useful information. Elsewhere, I find an imperfectly translated history of the site and photos including:

Monte Amiata is reckoned at 1,738 metres to be the second-highest volcano in Italy, but is now extinct and covered with forest. The abbey and its town are on the mountain flank, not the top (Roberto Ardigo photo):

2012-11-12

2012-11-11

An Ideological Kernel

A new article on the Great Stemma was published last year in Spanish, as I see from a new web search. In it, Helena de Carlos Villamarín seeks the reason for the inclusion of the diagram in the Codex of Roda. She argues that the diagram is the "ideological kernel of the Codex" and "points to the typological meaning of the textual ensemble, showing one of its interpretative clues to be the opposition between the Old and New Testament."

Perhaps. She says she is discussing all this "sin entrar a profundizar en el posible origen de estos textos o en sus avatares de transmisión". I would think that ignoring the possible origin of the genealogical diagram and its transmission history might make her interpretative argument rather vulnerable.

There is nothing wrong with speculating about the theological intentions of the Codex compiler, and de Carlos certainly knows the Codex as well as anyone today (this is her third published scholarly article about it), but surely one needs to also discuss what customers of the 10th-century book trade wanted (this was an expensive book to make), what was available for inclusion and why an illustrative frieze like the diagram was esteemed.

If the Christians of 10th century northern Spain knew that the diagram was of patristic origin, were aware that it had once existed in roll form and where it had been displayed, or even regarded it as an authoritative source, they might have used the diagram as a core document of their belief. If it was little known or obscure, it might have been taken up merely because of its decorative value. The errors in the diagram as copied leave the question open: did it go uncorrected because it was too authoritative to alter, or because the editors had a cavalier attitude to it?

The article is: "El Códice de Roda (Madrid, BRAH 78) como compilación de voluntad historiográfica". Edad Media: revista de historia, ISSN 1138-9621, 12 (2011), pp 119-142. Accessible here from Dialnet (which is an academic digitization portal, not a mobile-phone provider). (De Carlos's and other recent articles on the Codex by various authors are listed on Regesta Imperii.)

While I would not have expected de Carlos to have discovered my own Great Stemma research, which did not began to arrive online in bulk until 2010, I think she ought to have cited Christiane Klapisch-Zuber's L'ombre des ancêtres (2000) rather than an exploratory article published in 1991 by that author after her 1985-1986 Villa I Tatti stay in Florence. Klapisch-Zuber does not include the 1991 article any longer in her selected publications.

Admittedly my Spanish is too basic to go beyond the broad lines of argument of de Carlos, who teaches philology at the University of Santiago and edits an annual journal, Troianalexandrina, I find her re-interpretation of the genesis of the Codex an interesting contribution to the debate about the Great Stemma. In essence, she argues that the Codex contains two elements in tension: worldly history and biblical history, with a monastic editor trying to align them in a kind of harmony.

What I would have liked to see included would be some analysis of the diagram's history in Spain, including the known sightings of it in 772 and 672. Whether the Great Stemma in its 10th-century form really had kept its purely biblical character could also be debated. The Eusebian chronology and its synchronisms had long been introduced into the diagram by this stage via the Ordo Annorum Mundi. The version of the Great Stemma in the Codex of Roda is the closest in Spain to the lost original, and second only to the Florence version of the diagram as a witness, but we should not lose sight of the fact that the work was already at least 550 years old when the parchment for the Codex of Roda was still lying blank on a scriptorium shelf.

Perhaps. She says she is discussing all this "sin entrar a profundizar en el posible origen de estos textos o en sus avatares de transmisión". I would think that ignoring the possible origin of the genealogical diagram and its transmission history might make her interpretative argument rather vulnerable.

There is nothing wrong with speculating about the theological intentions of the Codex compiler, and de Carlos certainly knows the Codex as well as anyone today (this is her third published scholarly article about it), but surely one needs to also discuss what customers of the 10th-century book trade wanted (this was an expensive book to make), what was available for inclusion and why an illustrative frieze like the diagram was esteemed.

If the Christians of 10th century northern Spain knew that the diagram was of patristic origin, were aware that it had once existed in roll form and where it had been displayed, or even regarded it as an authoritative source, they might have used the diagram as a core document of their belief. If it was little known or obscure, it might have been taken up merely because of its decorative value. The errors in the diagram as copied leave the question open: did it go uncorrected because it was too authoritative to alter, or because the editors had a cavalier attitude to it?

The article is: "El Códice de Roda (Madrid, BRAH 78) como compilación de voluntad historiográfica". Edad Media: revista de historia, ISSN 1138-9621, 12 (2011), pp 119-142. Accessible here from Dialnet (which is an academic digitization portal, not a mobile-phone provider). (De Carlos's and other recent articles on the Codex by various authors are listed on Regesta Imperii.)

While I would not have expected de Carlos to have discovered my own Great Stemma research, which did not began to arrive online in bulk until 2010, I think she ought to have cited Christiane Klapisch-Zuber's L'ombre des ancêtres (2000) rather than an exploratory article published in 1991 by that author after her 1985-1986 Villa I Tatti stay in Florence. Klapisch-Zuber does not include the 1991 article any longer in her selected publications.

Admittedly my Spanish is too basic to go beyond the broad lines of argument of de Carlos, who teaches philology at the University of Santiago and edits an annual journal, Troianalexandrina, I find her re-interpretation of the genesis of the Codex an interesting contribution to the debate about the Great Stemma. In essence, she argues that the Codex contains two elements in tension: worldly history and biblical history, with a monastic editor trying to align them in a kind of harmony.

What I would have liked to see included would be some analysis of the diagram's history in Spain, including the known sightings of it in 772 and 672. Whether the Great Stemma in its 10th-century form really had kept its purely biblical character could also be debated. The Eusebian chronology and its synchronisms had long been introduced into the diagram by this stage via the Ordo Annorum Mundi. The version of the Great Stemma in the Codex of Roda is the closest in Spain to the lost original, and second only to the Florence version of the diagram as a witness, but we should not lose sight of the fact that the work was already at least 550 years old when the parchment for the Codex of Roda was still lying blank on a scriptorium shelf.

2012-11-10

Wooden Horse

An equi lignei gaming machine (photo and original) found near the hippodrome in Constantinople (Istanbul) is one of the treasures of the Bode Museum in Berlin. It seems to be one of the class of devices outlawed in 534 by the emperor Justinian:

This is a gaming machine. A commentary quoted on the museum page says the players placed four differently coloured marbles and let them run down through the holes. The marble which emerged first from the last hole produced a win for whoever had placed his bet on it. When this legal commentary was written is unclear.

The marble run or ball run in Berlin dates from about 500 and is a luxury stone-carved version of the machine. The marble is richly sculpted on the exterior with reliefs depicting the excitement of chariot racing: statues of horses, flute (aulos) players, men raising a banner, racetrack employees operating the draw for the teams and the start of a chariot race. The races appear to be conducted among teams of four horses, which was a passion among the people of Constantinople.

Jan Reichow refers to an account by the scholar Diether Roderich Reinsch and a museum guide by Arne Effenberger, quoted without page numbers or a proper bibliographic reference. The scholars appear to concur that the device was not a toy for a princeling but a capital investment for an entrepreneur in the equi lignei gambling trade, with the decoration on it conferring luxury and prestige, rather like the croupiers in casinos wearing tuxedos and bow ties to make the whole squalid experience seem as if it is high-class.

I made several marble runs from corrugated cardboard when I was about 10, and made another later as a father to amuse my sons. The frame was a cardboard carton and the tracks were strips of cardboard bent into V-cross-sections. With a box-cutter knife, I cut triangular holes in the carton to fit the tracks so that the marble could run through each track in succession. Children love marble runs, and this sort is easy to make and easy to recycle through the paper bank.

What makes a good marble run fun, until you have figured it out, is the unexpected way that the marble pops out on all sides of the block, rather like a mole showing up from a tunnel at an unexpected spot in my garden.

In my study of infographic history, the equi lignei device in Berlin firstly drew my attention because I wondered if its Late Antique users would have developed a scientific analysis of the path run through the device by the marble. An image on craft2eu.blog.de shows little holes at the side: it is not entirely clear if these are merely windows to show the players how far the marble has advanced or if these are exits for marbles that have been thrown out of the race:

Certainly some kind of mental projection of a path is a prerequisite for understanding a graph or a complex infographic like the Great Stemma.

The second aspect of interest is the illusionist potential of a marble run. Its operations are amusing because the marble can emerge, or at least be seen, where it is not expected. The marble seems to violate the rules of space by appearing magic-fashion in all sorts of unlikely places. It disrupts our sense of normal space. Some of the organization of the Great Stemma also breaks the rules of vision and is therefore slightly illusionist.

The marble run in Berlin at least confirms that the Late Antique world had a degree of experience with technical inventions that bent the rules of perception and vision when dealing with paths. This connects to the interesting technical guides by Hero of Alexandria including the one on ways to fake miracles in temples. These books were the subject of a post last year by Roger Pearse and there are links to the editions on the Wilbour Hall site.

Prohibemus etiam, ne sint equi lignei: sed si quis ex hac occasione vincitur, hoc ipse recuperaret: domibus eorum publicatis, ubi haec reperiuntur. (Text link.) Translation: We also prohibit (the game with) wooden horses; if any one loses in it, he may recover the loss. The houses of those where these games are played shall be confiscated. (English translation by Fred Blume: link.)Now plainly these wooden horses are not the sort used in the Greek capture of Troy, nor the sort that may have been vaulted over during Graeco-Roman gymnastic exercises. The museum has an online description of the item, which has exhibit number Ident.Nr. 1895, and a public image (bigger on the museum site):

The marble run or ball run in Berlin dates from about 500 and is a luxury stone-carved version of the machine. The marble is richly sculpted on the exterior with reliefs depicting the excitement of chariot racing: statues of horses, flute (aulos) players, men raising a banner, racetrack employees operating the draw for the teams and the start of a chariot race. The races appear to be conducted among teams of four horses, which was a passion among the people of Constantinople.

Jan Reichow refers to an account by the scholar Diether Roderich Reinsch and a museum guide by Arne Effenberger, quoted without page numbers or a proper bibliographic reference. The scholars appear to concur that the device was not a toy for a princeling but a capital investment for an entrepreneur in the equi lignei gambling trade, with the decoration on it conferring luxury and prestige, rather like the croupiers in casinos wearing tuxedos and bow ties to make the whole squalid experience seem as if it is high-class.

I made several marble runs from corrugated cardboard when I was about 10, and made another later as a father to amuse my sons. The frame was a cardboard carton and the tracks were strips of cardboard bent into V-cross-sections. With a box-cutter knife, I cut triangular holes in the carton to fit the tracks so that the marble could run through each track in succession. Children love marble runs, and this sort is easy to make and easy to recycle through the paper bank.

What makes a good marble run fun, until you have figured it out, is the unexpected way that the marble pops out on all sides of the block, rather like a mole showing up from a tunnel at an unexpected spot in my garden.

In my study of infographic history, the equi lignei device in Berlin firstly drew my attention because I wondered if its Late Antique users would have developed a scientific analysis of the path run through the device by the marble. An image on craft2eu.blog.de shows little holes at the side: it is not entirely clear if these are merely windows to show the players how far the marble has advanced or if these are exits for marbles that have been thrown out of the race:

Certainly some kind of mental projection of a path is a prerequisite for understanding a graph or a complex infographic like the Great Stemma.

The second aspect of interest is the illusionist potential of a marble run. Its operations are amusing because the marble can emerge, or at least be seen, where it is not expected. The marble seems to violate the rules of space by appearing magic-fashion in all sorts of unlikely places. It disrupts our sense of normal space. Some of the organization of the Great Stemma also breaks the rules of vision and is therefore slightly illusionist.

The marble run in Berlin at least confirms that the Late Antique world had a degree of experience with technical inventions that bent the rules of perception and vision when dealing with paths. This connects to the interesting technical guides by Hero of Alexandria including the one on ways to fake miracles in temples. These books were the subject of a post last year by Roger Pearse and there are links to the editions on the Wilbour Hall site.

2012-11-07

The Tamar Storyboard

I've been studying a curious little flow-chart embedded in the Great Stemma of the Morgan Beatus that describes Tamar's lucky-on-the-third-shot pregnancy in Genesis 38.

A revisor has added to this diagram a visualization of his own creation for one of the strangest sexual scandals in the Bible story, Tamar's seduction of Judah while pretending to be a veiled prostitute.

Tamar had been married to Judah's eldest son, Er. After she was widowed, Judah's second son Onan had sex with her but employed a crude form of contraception. Tamar then used a ruse to seduce her lecherous father in law and became pregnant. Her twin sons are either the sons or the grandsons of Judah, depending on your interpretation of this soap-opera plot.

Whether Shua, the wife of Judah, accepted this unusual family constellation is not recorded in Genesis, but the revisor devised the following compact visual summary of the story which retains for Shuah the place of honour in the emotionally tangled Judah household. It appears in flow-chart fashion in the Morgan Beatus like this:

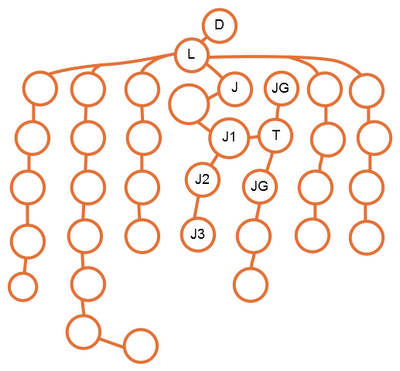

I have left out the text and instead used letters to mark the characters. Here, J is Judah, J1 and J2 are his first and second sons Er and Onan, and T is Tamar. Her twin children are marked JG, since the text marks them as sons of Judah and ambo gemini. Having the two twins arrayed in symmetry either side of their mother is a neat trick.

Perhaps it was Maius himself, the scribe-scholar who was in charge of making M 644 at the Morgan Library in New York, who devised this little flow chart. The roundel intervening between J and J1 is Shua, Judah's wife.

This addition, thus arranged, is only found in one other manuscript of the diagram, that made 100 years later by Facundus for King Fernando and Queen Sancha of León.

The whole group in the above sketch is composed of the six sons and daughter Dinah (D) of Leah (L). Links to online views of the manuscripts can be found on my manuscripts page.

A revisor has added to this diagram a visualization of his own creation for one of the strangest sexual scandals in the Bible story, Tamar's seduction of Judah while pretending to be a veiled prostitute.

Tamar had been married to Judah's eldest son, Er. After she was widowed, Judah's second son Onan had sex with her but employed a crude form of contraception. Tamar then used a ruse to seduce her lecherous father in law and became pregnant. Her twin sons are either the sons or the grandsons of Judah, depending on your interpretation of this soap-opera plot.

Whether Shua, the wife of Judah, accepted this unusual family constellation is not recorded in Genesis, but the revisor devised the following compact visual summary of the story which retains for Shuah the place of honour in the emotionally tangled Judah household. It appears in flow-chart fashion in the Morgan Beatus like this:

I have left out the text and instead used letters to mark the characters. Here, J is Judah, J1 and J2 are his first and second sons Er and Onan, and T is Tamar. Her twin children are marked JG, since the text marks them as sons of Judah and ambo gemini. Having the two twins arrayed in symmetry either side of their mother is a neat trick.

Perhaps it was Maius himself, the scribe-scholar who was in charge of making M 644 at the Morgan Library in New York, who devised this little flow chart. The roundel intervening between J and J1 is Shua, Judah's wife.

This addition, thus arranged, is only found in one other manuscript of the diagram, that made 100 years later by Facundus for King Fernando and Queen Sancha of León.

The whole group in the above sketch is composed of the six sons and daughter Dinah (D) of Leah (L). Links to online views of the manuscripts can be found on my manuscripts page.

2012-09-23

Farewell Hippolytus

In the past day I have been re-analysing some of the data which I examined and proceeded to describe two years ago in a blog post entitled Setback or Progress. At that time I was trying to discover the source of manuscript data which portrayed different ethnicities of the western world as tribal descendants of the biblical patriarch Noah. I was able to establish that this data was not part of the original version of the Great Stemma.

In the course of that research I took a closer look at the Chronicle (about 235 AD) of Hippolytus of Rome and formed the mistaken impression that Hippolytus had been a believer in a certain inflated and baroque chronology which had been abstracted from the biblical Book of Judges by an early Christian or Jewish chronographer.

Finding one's way among the subtle differences in Antique chronography (which is only preserved in fragmentary manuscripts based on repeated revisions of the original works) is an immensely tedious and complex affair which has never been the main focus of my research. The modern scholarly analysis of this material often employs elaborate arguments which magnify the faintest of evidence to arrive at some kind of usable conclusion.

In this case, much of the argument turns on how many phases make up the Book of Judges chronology and which phases were included. My Studia Patristica article, which is already in press, states:

Farewell Hippolytus: you are no longer on the Great Stemma team.

I have duly changed the page on my website that deals with the matter. In the Studia Patristica article, which can no longer be altered, I would now want to say that there are elements in the diagram which clash with the theories of Eusebius and plainly come from an older, as-yet unidentified chronographer. The misidentification of that chronographer as Hippolytus is a very minor issue, and does not in any way weaken the main thrust of the article: that the Liber Genealogus is a description of an early version of the Great Stemma diagram.

The necessary conclusion after dumping Hippolytus is that some other chronological tradition influenced the Great Stemma. Perhaps the chronographer involved was Julius Africanus, perhaps not. I am not intending to research the issue further. If my error proves to be the stalking horse for a future scholarly article by a specialist, so much the better. I would welcome scholars in the history-of-chronography field taking up the matter and giving it a thorough review.

In the course of that research I took a closer look at the Chronicle (about 235 AD) of Hippolytus of Rome and formed the mistaken impression that Hippolytus had been a believer in a certain inflated and baroque chronology which had been abstracted from the biblical Book of Judges by an early Christian or Jewish chronographer.

Finding one's way among the subtle differences in Antique chronography (which is only preserved in fragmentary manuscripts based on repeated revisions of the original works) is an immensely tedious and complex affair which has never been the main focus of my research. The modern scholarly analysis of this material often employs elaborate arguments which magnify the faintest of evidence to arrive at some kind of usable conclusion.

In this case, much of the argument turns on how many phases make up the Book of Judges chronology and which phases were included. My Studia Patristica article, which is already in press, states:

Distinctively Hippolytan elements in the account can be found for example in the period from Joshua to Eli inclusive, which is divided by the Great Stemma into 22 political phases. Hippolytan features here include the rule of an apocryphal judge Shamgar (6th phase) and his alter ego Samera (21st). Both phases were witnessed as present in the Great Stemma when it was seen by the author of the Liber Genealogus in 427, whereas their existence had been firmly ruled out by Eusebius. This would suggest that the author was either hostile to or ignorant of Eusebius.

However I have now read and re-read Rudolf Helm's 1955 edition of the Hippolytus Chronicle (particularly pages 164-167) and understood that (at least in the editor Helm's view), Hippolytus divided the period (Joshua to Eli inclusive) into only 20 phases and excluded the rule of an apocryphal judge Shamgar (6th phase) and his alter ego Samera (21st). These are tiny distinctions, but are enough to derail the argument that Hippolytus was involved.

Farewell Hippolytus: you are no longer on the Great Stemma team.

I have duly changed the page on my website that deals with the matter. In the Studia Patristica article, which can no longer be altered, I would now want to say that there are elements in the diagram which clash with the theories of Eusebius and plainly come from an older, as-yet unidentified chronographer. The misidentification of that chronographer as Hippolytus is a very minor issue, and does not in any way weaken the main thrust of the article: that the Liber Genealogus is a description of an early version of the Great Stemma diagram.

The necessary conclusion after dumping Hippolytus is that some other chronological tradition influenced the Great Stemma. Perhaps the chronographer involved was Julius Africanus, perhaps not. I am not intending to research the issue further. If my error proves to be the stalking horse for a future scholarly article by a specialist, so much the better. I would welcome scholars in the history-of-chronography field taking up the matter and giving it a thorough review.

2012-08-12

Subway Map

A nice piece appeared Monday in the International Herald Tribune on the 1972-79 New York City Subway Diagram. Alice Rawsthorn tells us that that the diagram was re-activated this year on the Weekender, a page that alerts travellers to weekend construction and maintenance work on the train system:

Some diagrams fail because they do not offer any advantages over existing methods: a very small "family tree" which only covers two generations – a person and their parents – provides no benefit compared to describing the family verbally. Others fail because they over-reach themselves.

New York City's Metropolitan Transportation Authority introduced a system diagram designed by Massimo Vignelli in 1972. It was based on Harry Beck's 1931 design for the London Underground. But New York City's rail engineers had built a system that could not be well diagrammed. The tangle of rail lines built through Lower Manhattan remained a tangle despite being schematized; the artwork was cluttered; worst of all, the design failed to connect to pre-existing mental representations of the city's bizarre geography. The MTA retired the Vignelli diagram in 1979 in the face of public criticism.

New York City's current subway diagram, which is like a skin superimposed on a simplified map of the city, is an easier connect between its designer and its readers. Even tourists find it easier to find their way with the current map.

Some diagrams fail because they do not offer any advantages over existing methods: a very small "family tree" which only covers two generations – a person and their parents – provides no benefit compared to describing the family verbally. Others fail because they over-reach themselves.

New York City's Metropolitan Transportation Authority introduced a system diagram designed by Massimo Vignelli in 1972. It was based on Harry Beck's 1931 design for the London Underground. But New York City's rail engineers had built a system that could not be well diagrammed. The tangle of rail lines built through Lower Manhattan remained a tangle despite being schematized; the artwork was cluttered; worst of all, the design failed to connect to pre-existing mental representations of the city's bizarre geography. The MTA retired the Vignelli diagram in 1979 in the face of public criticism.

New York City's current subway diagram, which is like a skin superimposed on a simplified map of the city, is an easier connect between its designer and its readers. Even tourists find it easier to find their way with the current map.

2012-07-27

Books of the Bible

I have chanced on a curious medieval infographic showing all the books of the Old Testament in stemmatic fashion, an idea that goes back to Cassiodorus (see my Cassiodorus abstract). The drawing, discovered with the help of Digital Scriptorium, is in the Lawrence Library at the University of Kansas and available in a high-resolution image.

It shows God as the origin node at the top, forking to the various books, for example the Pentateuch as a group of five at the top left, and employing trunk connectors below to connect the books of the prophets. The colours and style recall the Great Stemma.

The bibliographic information places the document (f. 2v of MS 9/2:29) in the 13th or 14th centuries and it is on the back of the final page of a Peter of Poitiers Compendium (see my list). It appears to be a continuation of the Compendium by the same scribe/artist. In the bibliographic description, the library considers it to be French.

It shows God as the origin node at the top, forking to the various books, for example the Pentateuch as a group of five at the top left, and employing trunk connectors below to connect the books of the prophets. The colours and style recall the Great Stemma.

The bibliographic information places the document (f. 2v of MS 9/2:29) in the 13th or 14th centuries and it is on the back of the final page of a Peter of Poitiers Compendium (see my list). It appears to be a continuation of the Compendium by the same scribe/artist. In the bibliographic description, the library considers it to be French.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)