To mentally "place" something is to know where it belongs. If you can place a hundred thousand words or faces or ideas, you command great knowledge. Often too, such a store enables you to quickly solve problems. Growing evidence suggests that "placing" is not merely a metaphor, but that we really do inwardly arrange concepts in spatial frames to think about them or recall them. It seems, indeed, that having extensive mental "spaces" is a key to intelligence.

One of the great goals of cognitive science is to understand how spatial-thinking skills assist -- and are perhaps fundamental to -- human thought. The mechanisms involved are not conscious ones, so simply reflecting on what it means to place, arrange and retrieve concepts in our mental space will not make us any the wiser.

How then are we to observe humans storing and retrieving ideas in the mental space they construct? The evidence we can use is of the indirect type, but useful nevertheless.

Metaphors and analogy provide one such monitor, most famously in our tendency to speak of time as "before" and "behind" us. Gestures are a second and rich source of evidence, since the upwards, downwards and sideways movements of the hands seem to unconsciously describe the mental space we are using. It has long been known as well that our eyes move in sympathy with our thoughts, so that a dart of the gaze to a place where there is in fact nothing to see is an indicator that we may be navigating an "inner" space. The devices we invent to visualize or spatialize our ideas, particularly diagrams, are a fourth tangent into this mysterious human capability. As I noted some time ago in another blog post, observing the thinking processes of the congenitally blind is a fifth method of observing pure visuo-spatial cognition.

At the annual conference of the Cognitive Science Society which has just finished in Philadelphia, interesting evidence was produced in two of these approaches.

In one paper, Gesture reveals spatial analogies during complex relational reasoning, Kensy Cooperrider with Dedre Gentner and Susan Goldin-Meadow observed 19 students explaining stockmarket bubbles and takeovers with spontaneous gestures to elucidate these complex mechanisms. "The participants constructed these spatial models fluidly and

more or less unconsciously," the paper notes. To me, this does indeed suggest a "spatial mind" contributing to human reasoning.

In another paper, Spatial Interference and Individual Differences in Looking at Nothing for Verbal Memory, Alper Kumcu and Robin L. Thompson used gaze direction to show that people use an imaginary mental space to remember things, in this case words. Some years ago, Martin Wallraff amusingly alluded to oral examinations where students say, "I can't remember what the book said, but I can remember exactly where on the page it said it." In this paper, the authors tested 48 students and found their eyes darted to the place on a tiny page where a word used to be, leading to the proposal that there is an "automatic, instantaneous spatial indexing

mechanism

for

words" in the mind.

As always, these experiments must be treated with a degree of caution. The subjects were students whose native language is English. We do not know if the results hold true in other cultures, or for the uneducated, or at other times in history. But they do suggest that we may one day succeed in mapping the human mental space and that the objective of this blog - understanding the "natural" mindlike ways to arrange information on pages and in diagrams - is indeed full of promise.

Cooperrider et al. note, "The ubiquity of

abstract spatial models

like

Venn diagrams, family trees,

and cladograms,

for example,

hints at the wider utility of spatial analogy in relational

reasoning."

Philadelphia also had a co-located diagrams meeting (mainly on Venn diagams) and a conference on Spatial Cognition, but the interesting papers from those events are sadly not online.

2016-08-14

2016-08-04

Vatican Mappamundi

In a previous post, I observed that the ancient world did not employ maps as we do. But certain brilliant foundational achievements in cartography are the work of antiquity. One is the Geography of Ptolemy of Alexandria. Another is the mappamundi, a late antique educational aid which visualized the whole known world in semi-schematic fashion.

The two oldest extant examples are the Vatican Mappamundi, copied between 762 and 777 according to Leonid Chekin, and the less detailed Albi Mappamundi (2nd half of the 8th century). France digitized the Albi map and won Unesco Memory of the World status for it last year. It is a wonderful moment to see that its equally old counterpart at the Vatican is now also online as of August 2, 2016. Here.

These two are far older artefacts than similar and justly celebrated maps of medieval provenance such as the Cotton Mappamundi, the Hereford Map, the (lost) Ebstorf Map, the London Psalter Map and the Beatus maps. All mappaemundi would appear to be evolutions from Late Antique seeds. The Vatican map, bound into Vat.lat.6018, shows the south at the top of the page. Patrick Gautier Dalché has superbly discussed their history, making certain essential points.

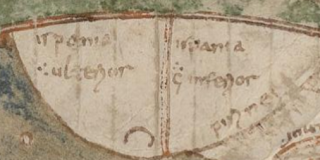

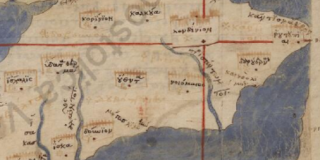

One is that the Vatican map cannot be a Merovingian-period design, but must be a traditionalizing copy of a diagram made well before the 8th century, since it distinguishes the Roman Empire's provinces of Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Inferior next to the Pyrenees (below): any educated 8th-century person would have to be aware that contemporary Spain had long since been unified under centuries of Visigothic rule before recently falling into Islamic hands, so this was even then a historical map:

The other key point is that the three mappaemundi at the Vatican, in Albi and in the Beatus Commentary on the Apocalypse appear to have three distinct and separate origins to them. Gautier Dalché asserts that all were compiled by late antique eruditio from educational lists of places, but I find his argument about this direction of conversion unconvincing.

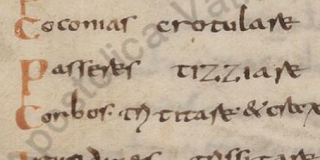

The mappamundi is bound into a miscellany which also includes some of Isidore's Etymologies (which is why it is sometimes oddly termed the "Pseudo-Isidorean Vatican Map"). There are two Trismegistos entries for the codex. One, TM 387432, notes the map as a source for the 1965 Itineraria et alia geographica (CCSL 175) pp. 455-463, and the other, TM 66146, points to Lowe, CLA 1 50, where palimpsested text faintly visible under folios 93, 98, 127, 128 is palaeographically identified as Italian of the 7th century. A celebrated list of animal sounds in Latin by Suetonius is also in the codex. Here is tizziare, the basis for titiatio, the Latin word adopted by David Meadows for "Twitter":

I do not know if the map has yet been plotted and published online, and am unable to find it sketched in Konrad Miller's great survey of mappaemundi (he does reproduce the Albi map), but in any case now you can see it in the original. It is an essential resource to everyone fascinated by the history of cartography.

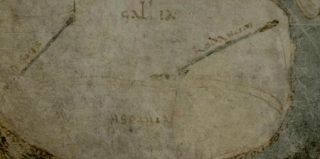

The French authorities noted in their Unesco application that the Vatican and Albi mappaemundi are the oldest non-abstract maps of the whole known world we possess (comparable only to the Peutinger Table, a medieval copy of a late antique plan of the world, and possibly two very ancient clay tablets (Mesopotamia, c. 2600 BC, and Babylonia, c. 600 BC) showing the world). These are presumably the Nuzi map tablet at the Semitic Museum in Harvard and the map tablet BM 92687 at the British Museum. Take a look at the Albi presentation page, the high-resolution digitization (one cannot link to pages, but seek page 115) and the lush but overdone video. Here is how the Albi Mappamundi shows Gallia and Hispania:

Here is the full list of 33 digitizations on August 2:

The two oldest extant examples are the Vatican Mappamundi, copied between 762 and 777 according to Leonid Chekin, and the less detailed Albi Mappamundi (2nd half of the 8th century). France digitized the Albi map and won Unesco Memory of the World status for it last year. It is a wonderful moment to see that its equally old counterpart at the Vatican is now also online as of August 2, 2016. Here.

These two are far older artefacts than similar and justly celebrated maps of medieval provenance such as the Cotton Mappamundi, the Hereford Map, the (lost) Ebstorf Map, the London Psalter Map and the Beatus maps. All mappaemundi would appear to be evolutions from Late Antique seeds. The Vatican map, bound into Vat.lat.6018, shows the south at the top of the page. Patrick Gautier Dalché has superbly discussed their history, making certain essential points.

One is that the Vatican map cannot be a Merovingian-period design, but must be a traditionalizing copy of a diagram made well before the 8th century, since it distinguishes the Roman Empire's provinces of Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Inferior next to the Pyrenees (below): any educated 8th-century person would have to be aware that contemporary Spain had long since been unified under centuries of Visigothic rule before recently falling into Islamic hands, so this was even then a historical map:

The other key point is that the three mappaemundi at the Vatican, in Albi and in the Beatus Commentary on the Apocalypse appear to have three distinct and separate origins to them. Gautier Dalché asserts that all were compiled by late antique eruditio from educational lists of places, but I find his argument about this direction of conversion unconvincing.

The mappamundi is bound into a miscellany which also includes some of Isidore's Etymologies (which is why it is sometimes oddly termed the "Pseudo-Isidorean Vatican Map"). There are two Trismegistos entries for the codex. One, TM 387432, notes the map as a source for the 1965 Itineraria et alia geographica (CCSL 175) pp. 455-463, and the other, TM 66146, points to Lowe, CLA 1 50, where palimpsested text faintly visible under folios 93, 98, 127, 128 is palaeographically identified as Italian of the 7th century. A celebrated list of animal sounds in Latin by Suetonius is also in the codex. Here is tizziare, the basis for titiatio, the Latin word adopted by David Meadows for "Twitter":

I do not know if the map has yet been plotted and published online, and am unable to find it sketched in Konrad Miller's great survey of mappaemundi (he does reproduce the Albi map), but in any case now you can see it in the original. It is an essential resource to everyone fascinated by the history of cartography.

The French authorities noted in their Unesco application that the Vatican and Albi mappaemundi are the oldest non-abstract maps of the whole known world we possess (comparable only to the Peutinger Table, a medieval copy of a late antique plan of the world, and possibly two very ancient clay tablets (Mesopotamia, c. 2600 BC, and Babylonia, c. 600 BC) showing the world). These are presumably the Nuzi map tablet at the Semitic Museum in Harvard and the map tablet BM 92687 at the British Museum. Take a look at the Albi presentation page, the high-resolution digitization (one cannot link to pages, but seek page 115) and the lush but overdone video. Here is how the Albi Mappamundi shows Gallia and Hispania:

Here is the full list of 33 digitizations on August 2:

- Barb.lat.3517.pt.A - just the binding: Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXI.fasc.81 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXII.fasc.82 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXII.fasc.83 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXII.fasc.84 - Details

- Ross.357 - Details

- Vat.ar.468.pt.3 - Details

- Vat.ebr.320 - Details

- Vat.ebr.327 - Details

- Vat.ebr.328 - Details

- Vat.ebr.331.pt.2 - Details

- Vat.ebr.333 - Details

- Vat.ebr.335 - Details

- Vat.ebr.337 - Details

- Vat.ebr.340 - Details

- Vat.ebr.342 - Details

- Vat.ebr.345 - Details

- Vat.ebr.347 - Details

- Vat.lat.30 - Details

- Vat.lat.158 - Details

- Vat.lat.273 - Details

- Vat.lat.316 - Details

- Vat.lat.648 - Details

- Vat.lat.706 - Details

- Vat.lat.760 - Details

- Vat.lat.877 - Details

- Vat.lat.880 - Details

- Vat.lat.881 - Details

- Vat.lat.1907 - Details

- Vat.lat.6018 - described above. Details

- Vat.lat.10696, one of the Vatican's most marvellous treasures, a single sheet from an otherwise lost Late Antique copy in uncial script of Livy's Ab Urbe Condita. This parchment had been used to wrap up some Christian relics from Palestine (mainly earth and stones from holy sites) kept since early medieval times in a box at the Lateran until it was realized in 1906 that the wrapping-tissue was itself an extraordinary relic. Discussed in a 2014 article by Julia Smith (PDF) from a book edited by Valerie Garver and Owen Phelan. What a discovery! Lowe's note (TM 66153) at CLA 1 57 suggests the uncial must date from the 4th or 5th century. Below is the first part. Details

- Vat.lat.13989 - Details

- Vat.lat.14207 - Details

Deschaux, Jocelyne. Mappa Mundi d’Albi. Albi, 2014. Unesco PDF

Chekin, Leonid S. ‘Easter Tables and the Pseudo-Isidorean Vatican Map’. Imago Mundi 51, no. 1 (1999): 13–23.

Gautier Dalché, Patrick. ‘L’Héritage Antique de Cartographie Médiévale: Les Problèmes et les Acquis’. In Cartography in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Fresh Perspectives, New Methods, edited by Richard J. A. Talbert and Richard Watson Unger. Leiden: Brill, 2008. Google Books

Miller, Konrad. Mappaemundi: die ältesten Weltkarten. 6 vols. Stuttgart: Roth, 1895. Online

2016-07-30

Off to the Seaside

I am guessing that the Vatican Library's digitizers are leaving Rome for summer at the seaside, and that a rush of 38 new items on the BAV digitizations portal will be the last for a few weeks. The current posted total is 5,169 codices, rolls and folders.

Of the 38 new items, 11 (Borg.Carte.naut and Pap.Bodmer) have long been available in digital form and their collections are simply being linked to for the first time. The remaining 27 items are:

Of the 38 new items, 11 (Borg.Carte.naut and Pap.Bodmer) have long been available in digital form and their collections are simply being linked to for the first time. The remaining 27 items are:

- Chig.M.IV.l - Details

- Chig.M.VIII.LXVII - collection of documents starting with a project for a new sacristy at St Peter's - Details

- Perg.Veroli.XX - from a collection of ancient deeds and charters from St Erasmo di Veroli in Italy, like the five following items - Details

- Perg.Veroli.XXI - Details

- Perg.Veroli.XXII - Details

- Perg.Veroli.XXIII - Details

- Perg.Veroli.XXIV - Details

- Perg.Veroli.XXXIII - Details

- Vat.ebr.301 - Details

- Vat.ebr.305 - Details

- Vat.ebr.308 - Details

- Vat.ebr.309 - Details

- Vat.ebr.310 - Details

- Vat.ebr.311 - Details

- Vat.ebr.312 - Details

- Vat.ebr.313 - Details

- Vat.ebr.314 - Details

- Vat.ebr.315 - Details

- Vat.ebr.316 - Details

- Vat.ebr.317 - Details

- Vat.ebr.318 - Details

- Vat.ebr.319 - Details

- Vat.ebr.322 - Details

- Vat.ebr.323 - Details

- Vat.ebr.326 - Details

- Vat.turc.141 - Details

- Vat.lat.332 - Jerome, Commentary on Minor Prophets, with Jerome getting round-shouldered from too much reading (and note the tricolor bookset on his bookshelf: product placement for France?) Details

- Pal. lat. 799 Iohannis Petrus de Ferarius : Dni. Iohannis Petri de Ferariis (sic) practica (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 797 Nicolai de Messiato: Sammelhandschrift (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 796 Bartholomaei Brixiensis: Sammelhandschrift (13. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 795 Henningi a Rod. processus iudiciarius (16. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 793 Durantis, Guilelmus: Guillielmi Duranti speculum iudiciale (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 790 Baron, Éguinaire: Dictata in nonnullos librorum Pandectarum titulos a Dn. Eguinario Barone Iurecons. clariss. apud Bituriges ordinario, excepta anno salutis 1546 (16. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 789 Lectura in Digestum (15.-16. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 788 Franciscus de Zaberellis; Ludovicus Pontani; Petrus ; Laurentii de Rudolphis: Sammelhandschrift (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 787 Azonis summa Codicis Iustiniani imp. (13.-14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 785 Munsteri Nurembergensis in Institutionum (Iustiniani imp.) libros adnotata (1529)

- Pal. lat. 784 Lectura in ius canonicum de Iudiciis Continua(ndis) ad totum librum precedentem secundum Goff(ridum) CX (1447)

- Pal. lat. 783 Formularium contractuum et instrumentorum (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 780 Tractatus plenissimus iuris, libri quatuor (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 779 Remissorium aureum iuris (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 777 Decisiones de conciliis Rote (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 776 Collectio inscripta (16. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 775 Collectio formularum Cancellariae Imperialis (16. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 772 Legis longobardorum libri tres (12. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 759 Codicis Iustiniani imp. libri IX (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 757 Codicis Iustiniani imp. libri IX (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 754 Digestum novum (13. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 753 Digestum novum (13. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 752 Digestum novum (13.-14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 751 Digestum novum (13.-14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 750 Digestum novum (13.-14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 749 Digestum novum (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 746 Infortiatum (13. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 745 Infortiatum (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 744 Infortiatum (Südfrankreich?, 14. Jh.)

2016-07-28

Summer of Ptolemy

Until about 25 years ago, it was unreflectingly supposed that the ancients used maps. It has now gradually achieved acceptance among historians (but perhaps not yet in the wider public) that scaled maps as we use them today are a cultural invention, attributable in the West at least to the medieval and modern period.

That is not to say that the ancients did not understand the idea of a map.

The archaeological record indicates that diagrams showing land from a birds-eye perspective were normal enough, but they tended to be schematic like our urban-train-line diagrams. The Turin Papyrus Map shows gold mines in Egypt. The gromatici of Classical Rome drew scaled survey plans. The 3rd century Forma Urbis Romae was the acme of such work, amounting to a plan of all Rome. But these showed land as contiguous property, not as a surface to cross from A to B.

The use of a large-scale map as a navigation aid was either not widely understood or rejected as ridiculously complicated to set up and deploy. Sailors noted bearings and relied on them. Land travellers perused itineraries, not maps. Late Antiquity created the Peutinger Diagram, a schematic of routes in the whole known world, but it was not made to scale.

Ptolemy, who seems to have lived in the 2nd century, wrote out a method for applying scale far larger than that of the gromatici to make maps of the world, and collected the longitudes and latitudes taken by sailors and travellers in about 8,000 locations in Europe, Africa and Asia to do so. He was far ahead of his time and was not followed. From an ancient perspective, the idea must have seemed counter-intuitive: in a world where 90 per cent of the land and all of the sea was empty waste, why employ time and costly papyrus to "dwell" on it?

A millennium later, the great scholar Manuel Planudes (c. 1260 – c. 1305) created maps from Ptolemy's geographical data. We now doubt that Planudes saw any Ptolemaic originals.

Among the most wonderful possessions of Federico da Montefeltro (1422-1482), the duke of Urbino and fabulously wealthy book collector, was a superb manuscript from about 1300, Urb.gr.82, preserving the Geography of Ptolemy (text) and the Planudes maps. It is one of the most important manuscripts of Ptolemy, preserving what is known as the Omega recension, and is known as U.

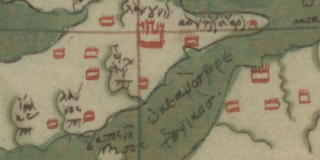

U came online as part of the digitization of the Vatican Library only a few weeks ago. Here is how it shows the region of London and the English Channel:

Federico owned a second copy (he was rich enough) made in the 15th century, Urb.gr.83, based on this recension, with 64 smaller regional maps and four large additional maps. This codex featured two decades ago in the Rome Reborn exhibition. It was uploaded to the online portal on July 26, 2016. Here is its take on the same region:

The Vatican is the essential place to go to recover the Geography. It also owns an essential manuscript of the Xi recension, Vat.gr.191, fols 127-172, or X, also online, but without maps, the arrival of which I covered in a blog post one year ago. The closely related A (Pal.gr 388) has not yet been digitized, nor have Z (Pal.gr. 314), V (Vat.gr. 177) or W (Vat.gr. 178).

For more details of the key manuscripts, see the Hans van Deukeren page. and also check the Daniel Mintz page. The definitive edition of the Geography was published by Stückelberger in 2006.

That is not to say that the ancients did not understand the idea of a map.

The archaeological record indicates that diagrams showing land from a birds-eye perspective were normal enough, but they tended to be schematic like our urban-train-line diagrams. The Turin Papyrus Map shows gold mines in Egypt. The gromatici of Classical Rome drew scaled survey plans. The 3rd century Forma Urbis Romae was the acme of such work, amounting to a plan of all Rome. But these showed land as contiguous property, not as a surface to cross from A to B.

The use of a large-scale map as a navigation aid was either not widely understood or rejected as ridiculously complicated to set up and deploy. Sailors noted bearings and relied on them. Land travellers perused itineraries, not maps. Late Antiquity created the Peutinger Diagram, a schematic of routes in the whole known world, but it was not made to scale.

Ptolemy, who seems to have lived in the 2nd century, wrote out a method for applying scale far larger than that of the gromatici to make maps of the world, and collected the longitudes and latitudes taken by sailors and travellers in about 8,000 locations in Europe, Africa and Asia to do so. He was far ahead of his time and was not followed. From an ancient perspective, the idea must have seemed counter-intuitive: in a world where 90 per cent of the land and all of the sea was empty waste, why employ time and costly papyrus to "dwell" on it?

A millennium later, the great scholar Manuel Planudes (c. 1260 – c. 1305) created maps from Ptolemy's geographical data. We now doubt that Planudes saw any Ptolemaic originals.

Among the most wonderful possessions of Federico da Montefeltro (1422-1482), the duke of Urbino and fabulously wealthy book collector, was a superb manuscript from about 1300, Urb.gr.82, preserving the Geography of Ptolemy (text) and the Planudes maps. It is one of the most important manuscripts of Ptolemy, preserving what is known as the Omega recension, and is known as U.

U came online as part of the digitization of the Vatican Library only a few weeks ago. Here is how it shows the region of London and the English Channel:

Federico owned a second copy (he was rich enough) made in the 15th century, Urb.gr.83, based on this recension, with 64 smaller regional maps and four large additional maps. This codex featured two decades ago in the Rome Reborn exhibition. It was uploaded to the online portal on July 26, 2016. Here is its take on the same region:

The Vatican is the essential place to go to recover the Geography. It also owns an essential manuscript of the Xi recension, Vat.gr.191, fols 127-172, or X, also online, but without maps, the arrival of which I covered in a blog post one year ago. The closely related A (Pal.gr 388) has not yet been digitized, nor have Z (Pal.gr. 314), V (Vat.gr. 177) or W (Vat.gr. 178).

For more details of the key manuscripts, see the Hans van Deukeren page. and also check the Daniel Mintz page. The definitive edition of the Geography was published by Stückelberger in 2006.

2016-07-27

Surpassing 5,000

With an enormous and unexpected display of energy, the Vatican Library released 253 new digitizations online on July 26, 2016 to surpass the bar of 5,000.

Only philanthropy can make this happen. The key assistance appears to be coming from NTT Data, the Japanese software company, which this month put some pepper in the fund-raising programme by announcing an attractive incentive for large donors: an ultra-close facsimile of a page from the Vatican Vergil (to be made by Canon). Contribute if you can: it will take immense resources and years of work to bring all 80,000 Vatican codices, rolls, papyri and sheafs of letters online.

Remarkable in this surge is the sudden arrival of 166 manuscripts from the great Renaissance library of Federico da Montefeltro (1422-1482), duke of Urbino, whose Italian library was perhaps the most costly cultural institution of his age. A new collection where digitization has just started is the Pergamene di Terracina.

The posted total of 5,131 continues to understate the true extent of the digitizations, as it does not include the many Pal.lat. manuscripts now online in an ancillary programme or isolated cases such as the Vatican's Bodmer Papyrus VIII. Here is the list of new arrivals:

Only philanthropy can make this happen. The key assistance appears to be coming from NTT Data, the Japanese software company, which this month put some pepper in the fund-raising programme by announcing an attractive incentive for large donors: an ultra-close facsimile of a page from the Vatican Vergil (to be made by Canon). Contribute if you can: it will take immense resources and years of work to bring all 80,000 Vatican codices, rolls, papyri and sheafs of letters online.

Remarkable in this surge is the sudden arrival of 166 manuscripts from the great Renaissance library of Federico da Montefeltro (1422-1482), duke of Urbino, whose Italian library was perhaps the most costly cultural institution of his age. A new collection where digitization has just started is the Pergamene di Terracina.

The posted total of 5,131 continues to understate the true extent of the digitizations, as it does not include the many Pal.lat. manuscripts now online in an ancillary programme or isolated cases such as the Vatican's Bodmer Papyrus VIII. Here is the list of new arrivals:

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.B.56 - Details

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.C.116 - Details

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.G.33 - Details

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.G.41 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XIX.fasc.70 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XIX.fasc.72 - Details

- Borg.ebr.16 - Details

- Borg.ebr.17 - Details

- Borg.turc.6 - Details

- Borgh.338 - Details

- Cappon.131 - Details

- Cappon.306 - Details

- Ferr.562 - Details

- Ott.lat.1210 - Details

- Ott.lat.1368 - Details

- Ott.lat.1417 - Details

- Perg.Terracina.1 - Details

- Perg.Terracina.2 - Details

- Perg.Terracina.3 - Details

- Perg.Terracina.4 - Details

- Perg.Terracina.5 - Details

- Perg.Terracina.6 - Details

- Reg.lat.1500 - Details

- Urb.gr.83 - Geography by Ptolemy. Full discussion in my separate blog post. Details

- Urb.lat.29 - Details

- Urb.lat.34 - Details

- Urb.lat.55 - Details

- Urb.lat.69 - Details

- Urb.lat.77 - Details

- Urb.lat.78 - Details

- Urb.lat.89 - Details

- Urb.lat.94 - Details

- Urb.lat.114 - Details

- Urb.lat.118 - Details

- Urb.lat.125 - Details

- Urb.lat.142 - Details

- Urb.lat.144 - Details

- Urb.lat.163 - Details

- Urb.lat.166 - Details

- Urb.lat.181 - Details

- Urb.lat.211 - Details

- Urb.lat.222 - Details

- Urb.lat.223 - Details

- Urb.lat.233 - Details

- Urb.lat.249 - Details

- Urb.lat.284 - Details

- Urb.lat.290 - Details

- Urb.lat.296 - Details

- Urb.lat.303 - Details

- Urb.lat.304 - Details

- Urb.lat.337 - Details

- Urb.lat.341 - Details

- Urb.lat.351 - Details

- Urb.lat.354 - Details

- Urb.lat.372 - Details

- Urb.lat.407.pt.1 - Details

- Urb.lat.448 - Details

- Urb.lat.449 - Details

- Urb.lat.470 - Details

- Urb.lat.472 - Details

- Urb.lat.479 - Details

- Urb.lat.485 - Details

- Urb.lat.489 - Details

- Urb.lat.494 - Details

- Urb.lat.502 - Details

- Urb.lat.503 - Details

- Urb.lat.506 - Details

- Urb.lat.507 - Details

- Urb.lat.509 - Details

- Urb.lat.512 - Details

- Urb.lat.517 - Details

- Urb.lat.518 - Details

- Urb.lat.519 - Details

- Urb.lat.521 - Details

- Urb.lat.533 - Details

- Urb.lat.535 - Details

- Urb.lat.536 - Details

- Urb.lat.540 - Details

- Urb.lat.544 - Details

- Urb.lat.545 - Details

- Urb.lat.549 - Details

- Urb.lat.557 - Details

- Urb.lat.558 - Details

- Urb.lat.564 - Details

- Urb.lat.567 - Details

- Urb.lat.572 - Details

- Urb.lat.573 - Details

- Urb.lat.578 - Details

- Urb.lat.583 - Details

- Urb.lat.587 - Details

- Urb.lat.588 - Details

- Urb.lat.591 - Details

- Urb.lat.593 - Details

- Urb.lat.594 - Details

- Urb.lat.609 - Details

- Urb.lat.611 - Details

- Urb.lat.612 - Details

- Urb.lat.614 - Details

- Urb.lat.622 - Details

- Urb.lat.626 - Details

- Urb.lat.628 - Details

- Urb.lat.629 - Details

- Urb.lat.631 - Details

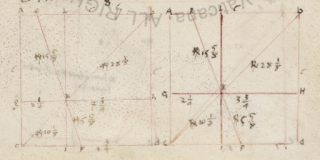

- Urb.lat.632 - the sole surviving copy of a treatise on 3D geometry, De quinque corporibus regularibus by Piero della Francesca, one of the card-carrying Renaissance men. Francesca is now known as a notable painter only, but in his time he was also an eminent mathematician. Here is a drawing (apparently by his own hand) from fol. 13r: More details in English. This featured in the Rome Reborn exhibition. More on the BAV details page.

- Urb.lat.634 - Details

- Urb.lat.635 - Details

- Urb.lat.636 - Details

- Urb.lat.637 - Details

- Urb.lat.640 - Details

- Urb.lat.641 - Details

- Urb.lat.642 - Details

- Urb.lat.643 - Details

- Urb.lat.646 - Details

- Urb.lat.647 - Details

- Urb.lat.648 - Details

- Urb.lat.649 - Details

- Urb.lat.650 - Details

- Urb.lat.651 - Details

- Urb.lat.652 - Details

- Urb.lat.653 - Details

- Urb.lat.654 - Details

- Urb.lat.655 - Details

- Urb.lat.658 - Details

- Urb.lat.659 - Details

- Urb.lat.660 - Details

- Urb.lat.661 - Details

- Urb.lat.664 - Details

- Urb.lat.665 - Details

- Urb.lat.667 - Details

- Urb.lat.668 - Details

- Urb.lat.670 - Details

- Urb.lat.671 - Details

- Urb.lat.672 - Details

- Urb.lat.675 - Details

- Urb.lat.676 - Details

- Urb.lat.681 - Details

- Urb.lat.683 - Details

- Urb.lat.684 - Details

- Urb.lat.685 - Details

- Urb.lat.686 - Details

- Urb.lat.690 - Details

- Urb.lat.691 - Details

- Urb.lat.692 - Details

- Urb.lat.693 - Details

- Urb.lat.694 - Details

- Urb.lat.696 - Details

- Urb.lat.697 - Details

- Urb.lat.698 - Details

- Urb.lat.699 - Details

- Urb.lat.701 - Details

- Urb.lat.702 - Details

- Urb.lat.703 - Details

- Urb.lat.704 - Details

- Urb.lat.705 - Details

- Urb.lat.708 - Details

- Urb.lat.709 - Details

- Urb.lat.710 - Details

- Urb.lat.713 - Details

- Urb.lat.714 - Details

- Urb.lat.716 - same content at Urb.lat.717 below - Details

- Urb.lat.717 - A book of esotericist poetry, De Gentilium Deorum Imaginibus by Lodovico Lazzarelli, from about 1475. Details in English at SLU. This also featured in Rome Reborn. This rather stoned person is Melponeme. It contains 27 full-page miniatures of personifications, including the planets, the muses, gods and goddesses, based on an educational prints series current at the time, the Mantegna Tarocchi. See also the BAV details.

- Urb.lat.719 - Details

- Urb.lat.720 - Details

- Urb.lat.721 - Details

- Urb.lat.724 - Details

- Urb.lat.727 - Details

- Urb.lat.728 - Details

- Urb.lat.729 - Details

- Urb.lat.730 - Details

- Urb.lat.735 - Details

- Urb.lat.736 - Details

- Urb.lat.737 - Details

- Urb.lat.738 - Details

- Urb.lat.739 - Details

- Urb.lat.741 - Details

- Urb.lat.742 - Details

- Urb.lat.743 - Details

- Urb.lat.744 - Details

- Urb.lat.746 - Details

- Urb.lat.751 - Details

- Urb.lat.767 - Details

- Urb.lat.769 - Details

- Urb.lat.780 - Details

- Urb.lat.782 - Details

- Urb.lat.783 - Details

- Urb.lat.784 - Details

- Urb.lat.785 - Details

- Urb.lat.804.pt.2 - Details

- Urb.lat.815.pt.2 - Details

- Vat.ar.136 - Details

- Vat.ar.175 - Details

- Vat.ar.468.pt.1 - Details

- Vat.ar.468.pt.2 - Details

- Vat.ar.1614 - Details

- Vat.ebr.1 - Details

- Vat.ebr.12 - Details

- Vat.ebr.13 - Details

- Vat.ebr.19 - Details

- Vat.ebr.21 - Details

- Vat.ebr.29 - Details

- Vat.ebr.100 - Details

- Vat.ebr.101 - Details

- Vat.ebr.102 - Details

- Vat.ebr.103 - Details

- Vat.ebr.118 - Details

- Vat.ebr.126 - Details

- Vat.ebr.133 - Details

- Vat.ebr.135 - Details

- Vat.ebr.186 - Details

- Vat.ebr.190 - Details

- Vat.ebr.196 - Details

- Vat.ebr.197 - Details

- Vat.ebr.199 - Details

- Vat.ebr.200 - Details

- Vat.ebr.203 - Details

- Vat.ebr.204 - Details

- Vat.ebr.206 - Details

- Vat.ebr.207.pt.1 - Details

- Vat.ebr.210 - Details

- Vat.ebr.211 - Details

- Vat.ebr.212 - Details

- Vat.ebr.264 - Details

- Vat.ebr.269 - Details

- Vat.ebr.276 - Details

- Vat.ebr.278 - Details

- Vat.ebr.281 - Details

- Vat.ebr.282 - Details

- Vat.ebr.287 - Details

- Vat.ebr.300 - Details

- Vat.ebr.302 - Details

- Vat.ebr.306 - Details

- Vat.ebr.307 - Details

- Vat.ebr.530.pt.2 - Details

- Vat.estr.or.111 - Japanese calligraphic roll: gold ink on dark blue paper

- Vat.lat.180 - Details

- Vat.lat.278 - Details

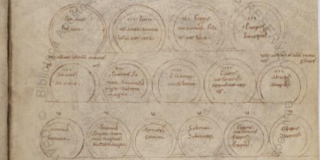

- Vat.lat.624 - with this extraordinary revision of a (classical?) Roman arbor juris (kinship diagram) in pyramidal form at fol. 105r: Note how the number of circles increases by one with each row as you follow it downwards. The scheme is a medieval revision of the so-called Type 4 arbor consanguinatis, as defined by Hermann Schadt - see my Missing Manual (DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4283.8002) for more information about this - Manuscript Details

- Vat.lat.795 - Details

- Vat.lat.797 - Details

- Vat.lat.803 - Details

- Vat.lat.809 - Details

- Vat.lat.823 - Details

- Vat.lat.838 - Details

- Vat.lat.845 - Details

- Vat.lat.848 - Details

- Vat.lat.853 - Details

- Vat.lat.854 - Details

- Vat.lat.863 - Details

- Vat.lat.884 - Details

- Vat.lat.13946 - Details

- Vat.lat.14745 - Details

- Vat.turc.139 - Details

- Vat.turc.391 - Details

2016-07-21

Vatican Shadows

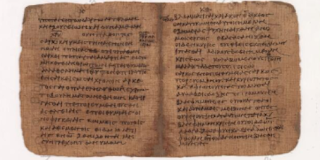

A couple of days ago, the Vatican library opened free online access to hi-res photos of what is generally believed to be one of the oldest books in the world, P75, the remains of a papyrus book of the Christian Gospels in Greek that is commonly dated to the third century. That turned out to be the story of the year on this blog, with over 900 reads, 85 retweets and 7,500 Twitter impressions.

[The next two grafs have been revised, after I realized that I had posted on the same topic in January this year, and clean forgot.] P75 got me interested in the library's other Bodmer papyrus, donated to it in 1969, the famous P72, shelved as Pap.Bodmer.VIII. The new digital site neither indexes nor mentions it on the front page of the digital manuscripts site.

The old BAV portal's link still gives you access to Pap.Bodmer.VIII, a booklet of epistles, containing all the text of 1 Peter, 2 Peter, and Jude. [This link I am giving you is not a secret, but rather one forgotten by the designers of the new portal. My apologies for overstating the case, when I first put this post up and claimed I had "discovered" the link.]

The writing on the P72 papyrus is thought to date to the 3rd or 4th century, roughly of the same period as the Codex Vaticanus, probably the world's oldest intact parchment codex.

The Wikipedia entry notes that P72 was dismembered from the "Bodmer Miscellaneous Codex," a little book dug from the sands of Egypt in which other works were: Nativity of Mary, the apocryphal correspondence of Paul to the Corinthians, the Eleventh Ode of Solomon, Melito's Homily on the Passover, a fragment of a hymn, the Apology of Phileas, and Psalm 33 and 34.

We don't know if P72, where you can see the folds in the folios, is the oldest papyrus codex in existence, but Brent Nongbri, the Australian scholar, has recently argued: "It would seem that P.Bodm. VIII had a previous life, in which it preceded another work that was later removed when P.Bodm. VIII became part of the ‘Miscellaneous’ or ‘Composite’ codex." So it could be years or decades older than other parts of the codex.

You can read his short paper on his Academia.edu page, as well as a blog post he wrote.

As for P75 (the gospels), its date of making has long been estimated to be the 3rd century, but Nongbri published a critique this year in the Journal of Biblical Literature where he argued that this date is slapdash (my word, not his) and that the correct date is more likely to be 4th century, more or less of the same period as the Codex Vaticanus. I'll have more as the story continues.

Aside from all this excitement, the BAV has this week released an additional 34 items. Here is the full list:

[The next two grafs have been revised, after I realized that I had posted on the same topic in January this year, and clean forgot.] P75 got me interested in the library's other Bodmer papyrus, donated to it in 1969, the famous P72, shelved as Pap.Bodmer.VIII. The new digital site neither indexes nor mentions it on the front page of the digital manuscripts site.

The old BAV portal's link still gives you access to Pap.Bodmer.VIII, a booklet of epistles, containing all the text of 1 Peter, 2 Peter, and Jude. [This link I am giving you is not a secret, but rather one forgotten by the designers of the new portal. My apologies for overstating the case, when I first put this post up and claimed I had "discovered" the link.]

The writing on the P72 papyrus is thought to date to the 3rd or 4th century, roughly of the same period as the Codex Vaticanus, probably the world's oldest intact parchment codex.

The Wikipedia entry notes that P72 was dismembered from the "Bodmer Miscellaneous Codex," a little book dug from the sands of Egypt in which other works were: Nativity of Mary, the apocryphal correspondence of Paul to the Corinthians, the Eleventh Ode of Solomon, Melito's Homily on the Passover, a fragment of a hymn, the Apology of Phileas, and Psalm 33 and 34.

We don't know if P72, where you can see the folds in the folios, is the oldest papyrus codex in existence, but Brent Nongbri, the Australian scholar, has recently argued: "It would seem that P.Bodm. VIII had a previous life, in which it preceded another work that was later removed when P.Bodm. VIII became part of the ‘Miscellaneous’ or ‘Composite’ codex." So it could be years or decades older than other parts of the codex.

You can read his short paper on his Academia.edu page, as well as a blog post he wrote.

As for P75 (the gospels), its date of making has long been estimated to be the 3rd century, but Nongbri published a critique this year in the Journal of Biblical Literature where he argued that this date is slapdash (my word, not his) and that the correct date is more likely to be 4th century, more or less of the same period as the Codex Vaticanus. I'll have more as the story continues.

Aside from all this excitement, the BAV has this week released an additional 34 items. Here is the full list:

- Vat.ebr.32, - Details

- Vat.ebr.33, - Details

- Vat.ebr.230, - Details

- Vat.ebr.250, - Details

- Vat.ebr.270.pt.1, - Details

- Vat.ebr.270.pt.2 - Details

- Vat.ebr.271 - Details

- Vat.ebr.283 - Details

- Vat.ebr.286 - Details

- Vat.ebr.289 - Details

- Vat.ebr.296 - Details

- Vat.lat.276 - a 12th-century Augustine in Caroline minuscule with some Beneventan script on fols 258v-260v (my thanks to AaronM on Twitter for this info: https://twitter.com/gundormr/status/756196478452924416), Details

- Vat.lat.288 - Ambrose of Milan, Details

- Vat.lat.295 - Ambrose, Details

- Vat.lat.296 - a 10th-century Ambrose, Details

- Vat.lat.373 - made for the Renaissance bishop Pietro del Monte (c. 1400–57), from fol 111 he added the prologue to his Repertorium utriusque iuris, a major legal text - Details

- Vat.lat.650 - a 10th-century compilation with Alcuin and others, many very faint pages have also been scanned with what seems to be ultraviolet light. Details

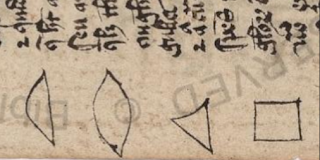

- Vat.lat.674 - 14th century theological and scientific: here are some shape diagrams in the margin in a geometrical piece (140v, rotated): second half empty, Details

- Vat.lat.740 - Aquinas, Details

- Vat.lat.773 - Details

- Vat.lat.775 - Details

- Vat.lat.778 - Details

- Vat.lat.779 - Details

- Vat.lat.786 - Details

- Vat.lat.789 - Details

- Vat.lat.813 - Details

- Vat.lat.819 - Details

- Vat.lat.834 - Giles of Rome, Quaestiones, Details

- Vat.lat.836 - Giles of Rome, c. 1243-1316, Commentarius in librum II Sententiarum, Details

- Vat.lat.837 - ditto, Details

- Vat.lat.852 - Details

- Vat.lat.866 - Details

- Vat.lat.875 , Details,

- Vat.lat.14747 , an 18th century fair copy cataloguing the authors in the papal collection of printed books, the seventh volume, arranged by names, S-Z. Here is the pen drawing for S:

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)