In a

previous post, I observed that the ancient world did not employ maps as we do. But certain brilliant foundational achievements in cartography are the work of antiquity. One is the

Geography of Ptolemy of Alexandria. Another is the mappamundi, a late antique educational aid which visualized the whole known world in semi-schematic fashion.

The two oldest extant examples are the Vatican Mappamundi, copied between 762 and 777 according to Leonid Chekin, and the less detailed Albi Mappamundi (2nd half of the 8th century). France digitized the Albi map and won Unesco Memory of the World status for it last year. It is a wonderful moment to see that

its equally old counterpart at the Vatican is now also online as of August 2, 2016.

Here.

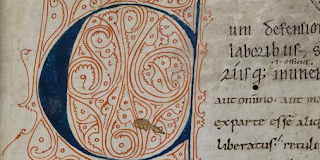

These two are far older artefacts than similar and justly celebrated maps of medieval provenance such as the Cotton Mappamundi, the Hereford Map, the (lost) Ebstorf Map, the London Psalter Map and the Beatus maps. All mappaemundi would appear to be evolutions from Late Antique seeds. The Vatican map, bound into

Vat.lat.6018, shows the south at the top of the page. Patrick Gautier Dalché has superbly discussed their history, making certain essential points.

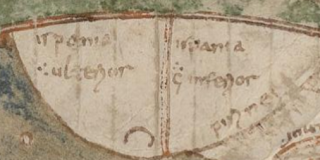

One is that the Vatican map cannot be a Merovingian-period design, but must be a traditionalizing copy of a diagram made well before the 8th century, since it distinguishes the Roman Empire's provinces of Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Inferior next to the Pyrenees (below): any educated 8th-century person would have to be aware that contemporary Spain had long since been unified under centuries of Visigothic rule before recently falling into Islamic hands, so this was even then a

historical map:

The other key point is that the three mappaemundi at the Vatican, in Albi and in the Beatus

Commentary on the Apocalypse appear to have three distinct and separate origins to them. Gautier Dalché asserts that all were compiled by late antique

eruditio from educational lists of places, but I find his argument about this direction of conversion unconvincing.

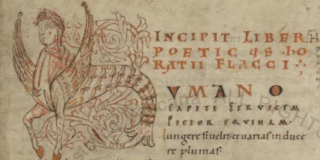

The mappamundi is bound into a miscellany which also includes some of Isidore's

Etymologies (which is why it is sometimes oddly termed the "Pseudo-Isidorean Vatican Map").

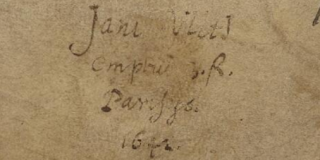

There are two Trismegistos entries for the codex. One,

TM 387432, notes the map as a source for the 1965

Itineraria et alia geographica (CCSL 175) pp. 455-463, and the other,

TM 66146, points to Lowe, CLA 1 50, where palimpsested text faintly visible under folios 93, 98,

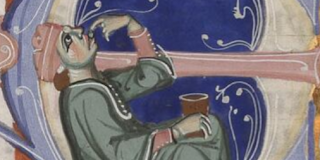

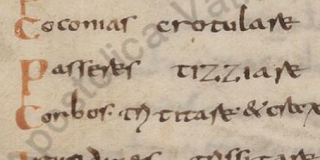

127, 128 is palaeographically identified as Italian of the 7th century. A celebrated list of animal sounds in Latin by Suetonius is also in the codex. Here is

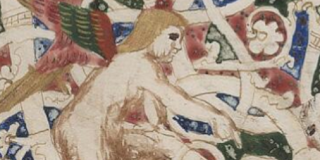

tizziare, the basis for

titiatio, the Latin word adopted by

David Meadows for "Twitter":

I do not know if the map has yet been plotted and published online, and am unable to find it sketched in Konrad Miller's great survey of mappaemundi (he does

reproduce the Albi map), but in any case now you can see it in the original. It is an essential resource to everyone fascinated by the history of cartography.

The French authorities noted in their Unesco

application that

the Vatican and Albi mappaemundi are

the oldest non-abstract maps of the

whole known world we possess (comparable only to the Peutinger Table, a

medieval copy of a late antique plan of the world, and possibly two very

ancient clay tablets (Mesopotamia, c. 2600 BC, and Babylonia, c. 600 BC) showing the world). These are presumably the Nuzi map tablet at the Semitic Museum in Harvard and the map tablet BM 92687 at the British Museum. Take a look at the Albi

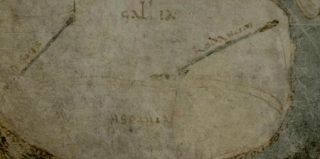

presentation page, the high-resolution

digitization (one cannot link to pages, but seek page 115) and the lush but overdone video. Here is how the Albi Mappamundi shows Gallia and Hispania:

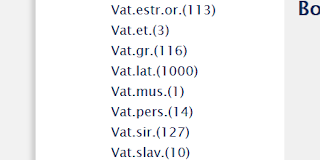

Here is the full list of 33 digitizations on August 2:

- Barb.lat.3517.pt.A - just the binding: Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXI.fasc.81 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXII.fasc.82 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXII.fasc.83 - Details

- Borg.copt.109.cass.XXII.fasc.84 - Details

- Ross.357 - Details

- Vat.ar.468.pt.3 - Details

- Vat.ebr.320 - Details

- Vat.ebr.327 - Details

- Vat.ebr.328 - Details

- Vat.ebr.331.pt.2 - Details

- Vat.ebr.333 - Details

- Vat.ebr.335 - Details

- Vat.ebr.337 - Details

- Vat.ebr.340 - Details

- Vat.ebr.342 - Details

- Vat.ebr.345 - Details

- Vat.ebr.347 - Details

- Vat.lat.30 - Details

- Vat.lat.158 - Details

- Vat.lat.273 - Details

- Vat.lat.316 - Details

- Vat.lat.648 - Details

- Vat.lat.706 - Details

- Vat.lat.760 - Details

- Vat.lat.877 - Details

- Vat.lat.880 - Details

- Vat.lat.881 - Details

- Vat.lat.1907 - Details

- Vat.lat.6018 - described above. Details

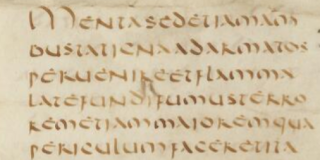

- Vat.lat.10696, one of the Vatican's most marvellous treasures,

a single sheet from an otherwise lost Late Antique copy in uncial script of Livy's Ab Urbe Condita. This parchment had been used to wrap up some Christian relics from Palestine (mainly earth and stones from holy sites) kept since early medieval times in a box at the Lateran until it was realized in 1906 that the wrapping-tissue was itself an extraordinary relic. Discussed in a 2014 article by Julia Smith (PDF) from a book edited by Valerie Garver and Owen Phelan. What a discovery! Lowe's note (TM 66153) at CLA 1 57 suggests the uncial must date from the 4th or 5th century. Below is the first part. Details

- Vat.lat.13989 - Details

- Vat.lat.14207 - Details

This is Piggin's Unofficial List number 64. If you have corrections or additions, please use the comments box below. Follow me on Twitter (@JBPiggin) for news of more additions to Digita Vaticana.

Deschaux, Jocelyne.

Mappa Mundi d’Albi. Albi, 2014.

Unesco PDF

Chekin, Leonid S. ‘Easter Tables and the Pseudo-Isidorean Vatican Map’. Imago Mundi 51, no. 1 (1999): 13–23.

Gautier Dalché, Patrick. ‘L’Héritage Antique de Cartographie Médiévale: Les Problèmes et les Acquis’. In

Cartography in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Fresh Perspectives, New Methods, edited by Richard J. A. Talbert and Richard Watson Unger. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

Google Books

Miller, Konrad.

Mappaemundi: die ältesten Weltkarten. 6 vols. Stuttgart: Roth, 1895.

Online