A book published a couple of months ago by the German cognitive scientist Markus Knauff contains some remarkable new evidence and discussion about the seat of human reasoning. Summing up a couple of decades of experiments, he argues that a brain structure which can demonstrably be shown to analyse and reason is the so-called dorsal pathway.

This is the "where" stream which handles our awareness of space, our actions and, as a recent review article by Borst and others argues, our expectations. (All references below.) There has been some criticism in another review article by Schenk and others of the claims that this pathway is entirely distinct from the ventral or "what" pathway, but the dichotomy does seem to be holding up well.

In

Space to Reason: A Spatial Theory of Human Thought, Knauff emphasizes that this dorsal pathway is not a self-aware channel, so it is easy to overlook its operations. It shows up in brain imaging, but we cannot examine it by introspection.

... people certainly have no clue about the mechanisms that work on a symbolic spatial array, and they are certainly not aware of a complexity measure that results in certain preferences. (190) [and quoting Goodale & Westwood:] ... the processing of spatial information in the dorsal stream is impenetrable to our conscious awareness. (191)

Knauff does not mention diagrams in his book at all. Most of his experiments involve reasoning about very simple problems such as:

The blue Porsche is parked to the left of the red Ferrari.

The red Ferrari is parked to the left of the green Beetle.

Is the blue Porsche parked to the left or to the right of the green Beetle? (2)

However he proposes that these yield valid data about problems such as:

If the teacher is in love, then he likes pizza.

The teacher is in love.

Does it follow that the teacher likes pizza? (95)

The cars problem is not difficult but it requires effortful thinking, whereas the

if problem is instantly understandable. You will probably have guessed at the conclusion before you were conscious of reading the last line, which is said by some authors to be a characteristic of dorsal cognition.

Now there are two competing established accounts of what is going on: one is that we might pretend to see a real teacher whom we know and because we are so smart at understanding from sight, and teasing meaning from sight. we can deduce from visual indications that he is biting a slice of pizza that he must therefore be in love, just as we deduce from a distended belly that a woman is pregnant.

The rival account - propositional reasoning - maintains that we have a kind of machine language inside our brains, a computational logic. It does not use a language like English, but perhaps a language like JavaScript, and it tells us from the

if what the only logical conclusion is.

Knauff argues for a third option: if I interpret this correctly, we have a black-box process in which we use the dorsal channel to simulate the problem as if we were perceiving something real. A mental model is constructed where the teacher, his state of romantic excitement and the pizza are encoded as spatial entities. Putting them in the only possible logical order allows us to grasp the conclusion.

The heart of his argument is that evidence shows the ventral stream need not be involved. One of the salient points about the spatial-thinking model is that

the mental representation excludes all unnecessary information. The

shape or colour of the cars or the exact distance between them does not

need to be encoded, nor does the shape of the teacher's face or the

flavour of the pizza.

As I have said, Knauff does not mention diagrams, let alone the Great Stemma or the

Compendium of Petrus Pictaviensis. But the sense of excitement his book generates in the diagram researcher comes from the fact that the sparse, austere mental models he envisages as the bearers of human reasoning resemble the simpler sort of diagrams that are drawn on paper or on displays.

Reviel Netz suggests in

The Archimedes Codex and his various articles that the Greek mathematician did not use diagrams to merely illustrate ideas that he had been thinking through in some propositional fashion. Archimedes was doing mathematics by manipulating spatial representations in his head. Since he was thinking about space, not propositions, the diagrams were the closest external representation to his raw thoughts. As far as I can guess, Netz's ideas are partly rooted in the ideas about external representations generated by externalists in philosophy of mind debates over the past 20 years.

Stemmata and diagrammatic chronicles are not direct reasoning tools in quite the way that geometrical drawings are. Geometry can yield mathematical proofs without numbers or words, whereas chronicles are not there to reason with, but usually serve to re-express histories or genealogies that have already been set down in textual form.

Their purpose is communication. I have always maintained that they are a form of direct author-to-reader communication which eschews the need to convert their content into language. An author massages his ideas into the most lucid spatial arrangement he can come up with, puts them on paper, and the reader's spatial reasoning abilities are sufficient to decode what is meant with a minimum of textual input.

The nearest that Knauff comes to this is when he suggests that there is a kind of diagrammatic substrate to reasoning, and compares this to subway or underground-rail diagrams:

I

used the metaphor of a subway map to show that a qualitative

representation does not display the shares and sizes of the stations or

metrical distances between the stations but only represents the data

that preserve spatial relations between stations and lines, for example,

that one line connects with another. ... a visual image is completely

different from a subway map. It is more like a topographical map ...

that captures distances, streets, buildings, landform information, and

so on. In contrast, spatial layout models are like schematic subway

maps... (192)

His findings and his interpretation have some interesting implications for diagram studies. If the mental model in our heads is somewhat like a diagram, it ought to be possible to devise diagrams that can inspire such mental models with a minimum of translation.

Since the precise distances between the elements, and their sizes, do not encode any information, both of the following work equally well.

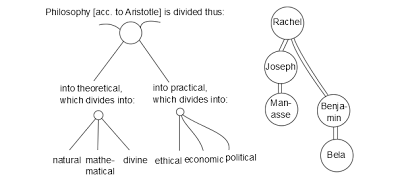

The left diagram is a 6th-century classification system drawn by Cassiodorus, while the right one comes from the 5th-century Great Stemma. I have translated the text from Latin to English. Whether the circles are large, small or non-existent, or whether the text is inside them or out, does not matter. Spatial reasoning merely needs apartness.

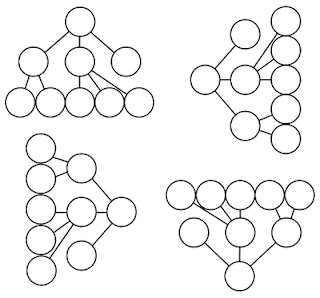

Overall orientation does not encode information, so all of the following directions of ramification are functionally equivalent.

Spatial reasoning is also likely to be highly tolerant of defective alignment, so that curved or crooked pathways in a diagram do not make them ineffective.

If this is correct, node-link diagrams which use a spatial encoding

to express hierarchical relationships are likely to be a powerful means

to manipulate a complex type of data while

directly engaging with human intelligence. Working pragmatically and without any scientific evidence from

cognitive research, the Late Antique inventors of node-link diagrams established an effective means of simplifying information without losing its essential structure.

Borst, Grégoire, William L. Thompson, and Stephen M. Kosslyn. ‘Understanding the Dorsal and Ventral Systems of the Human Cerebral Cortex: Beyond Dichotomies.’ American Psychologist 66, no. 7 (2011): 624–632. doi:10.1037/a0024038.

Goodale, Melvyn A., and David A. Westwood. ‘An Evolving View of Duplex Vision: Separate but Interacting Cortical Pathways for Perception and Action’. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 14, no. 2 (April 2004): 203–211. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.002.

Knauff, Markus. Space to Reason: A Spatial Theory of Human Thought. MIT Press, 2013.

Netz, Reviel, and William Noel. The Archimedes Codex. Revealing the Secrets of the World’s Greatest Palimpsest. London. Orion, 2007.

Schenk, Thomas, and Robert D. McIntosh. ‘Do We Have Independent Visual Streams for Perception and Action?’ Cognitive Neuroscience 1, no. 1 (26 February 2010): 52–62. doi:10.1080/17588920903388950.