When a video-rich website fails to load to your mobile because you drove out of cell range or your data plan maxed out, you're a victim of data bloat. To make files more portable, programmers constantly seek new ways to compress them in size. Now, it turns out, the problem was licked 1,000 years ago.

One way to compress a text file is to shorten its commonest words. Medieval scribes knew that. They had a long repertoire of abbreviations, but this only shortens a file by about 5 per cent.

A modern way is to deconstruct the document, and provide a web client with compact instructions about how to rebuild it. That's how a browser reconstitutes a page using bare-bones text in a HTML file, prettied up by the look, sizing and positioning saved in a CSS file. All the objects are instances of classes of some sort, so they don't have to be repetitively described.

The result: tiny files can create big, bright web pages.

This week I discovered evidence that medieval information technologists used the same technique, separating content from form to make a graphics file more portable.

The story starts with the Bible of Ripoll, a Latin bible illuminated in Ripoll, Spain in about 1025 CE and now kept at the Vatican. It contains a handwritten list of only the text of a late antique infographic, the Great Stemma. This huge diagram devised in about 420 CE generally needs up to 18 pages to display, but in the Ripoll Bible, the text-only version fits in a little over five pages.

The mystery here is: why was the Ripoll list made? What use is a non-graphic version of a diagram? No one has ever been able to solve that puzzle about this manuscript. Let's look at a sample of the Ripoll text, where it quotes the Gospel of Matthew 1:4-5 "Nahshon was father of Salmon; Salmon was father of Boaz, ... Boaz was father of Obed, whose mother was Ruth. Obed was father of Jesse."

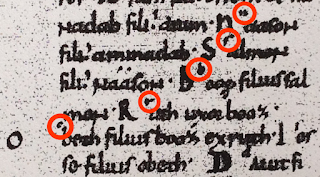

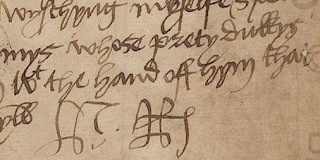

In the following image, I have circled five puzzling extra letters in the Latin text in red. After the initial capital of each name, the same letter in miniscule has been inserted. The letter with Salmon is the normal "s" in Carolingian script, while the "o" with Obed is damaged but clear enough. To exercise your grey cells, I have not marked the "i" of Jesse and the "d" of David. Try to find them.

For reading purposes only, these added letters would be completely superfluous. I've never seen the like of them. But after some thought, I believe I can explain the insertions.

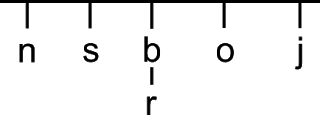

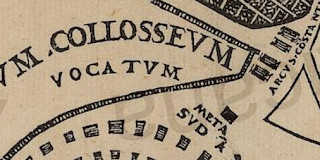

In my view, this text-only file was not originally something that stood alone, but must have been intended for use in conjunction with a positioning document. I would conjecture that the document would have looked something like this in its section with the five generations to Jesse:

The small letters here match with the keys in the text file. The text has thus been divided into snippets, just as a HTML text is marked up with tags in modern web documents. Tagging is a type of metadata to describe a document's presentation. It relies on a set of definitions held elsewhere.

For the Ripoll document, which is not explained in any way, an explanation must have existed elsewhere as to what the reconstituted document was to be: a visualization of a biblical genealogy where the persons (and historical periods) were represented by circles. This would be the equivalent of a modern "document type declaration".

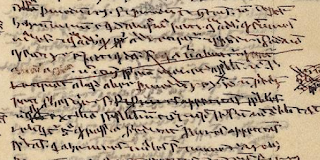

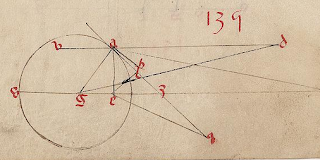

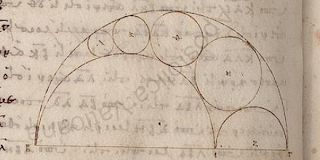

Using an exemplar composed of three compact files, any smart scribe would have been able to reconstitute the original diagram like this:

In this version, dating to about 672 CE and preserved in a later Italian manuscript, Plut 20.54 in Florence, the five names of the men are in the top row. Ruth's is the centre roundel in the lower row.

Why the proper diagram was never reconstructed and inserted in the beautiful Ripoll Bible (Vat. lat. 5729, still not online) is unclear. Perhaps its positioning file was missing or damaged. Perhaps there was a misunderstanding in the scriptorium.

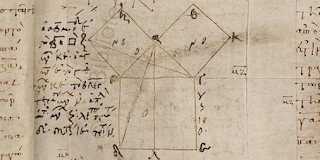

Now I must emphasize I am not claiming Hyper Text Markup Language was devised in medieval times: I am using that term as an approximation for meta-data markup at the phrase level. Nor have I discovered the positioning document itself. I can only guess that it once existed. But I think we now have a cogent explanation of the function of these miniscule letters, and thus of the Ripoll list itself. Other parts of it have large initials in the margins (like the big O of Obeth above) which may have also been keys. I am not aware of any medieval or ancient source that describes this method of conveying a diagram, nor do I know of any modern scholar who has suggested such a bright idea was even possible.

But the idea makes eminent sense if one considers that parchment was expensive and copying the Great Stemma accurately (it contains about 540 names and is fiendishly complicated) would have taken a scribe four or five days. To have a master copy in this very compact form (the whole Great Stemma structure could be reproduced on the equivalent of two A4 sheets) which could be taken from place to place easily and used to make local copies matches what we know about ancient and medieval book production methods: that exemplars or master copies were relied on.

The use of metadata tags to do so is a major surprise and changes what we know about the origins of modern information science. It also suggests a method that might have been used to distribute other charts such as the Late Antique Peutinger Diagram.

Disgrace

41 minutes ago