The oldest treasures this time are from the chapter library (Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.) which has only been part of the BAV since 1940.

Nearly half the items this week come from the great Renaissance library created by Federico da Montefeltro, duke of Urbino, who died in 1482 after a rambunctious life as a brutal mercenary general (he never fought for free) and refined man of culture (he had his own team of scribes at Urbino and a library considered the greatest in Italy after the pope's).

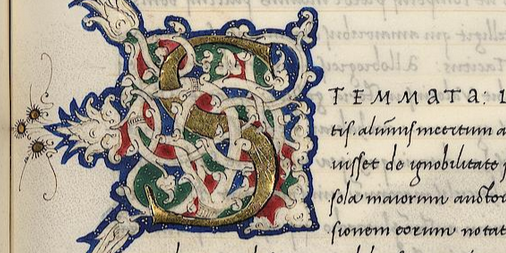

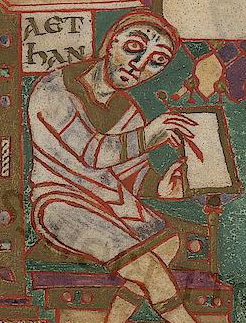

A couple of centuries after his death, that envied library was integrated into the Papal Library at the Vatican in 1657. We are now all privileged to be able to read Federico's exquisite books online. Here is a fine illuminated capital "S" from one of them, Urb. lat. 348, in a passage explaining the word stemmata.

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.A.13, Augustine of Hippo, sermons

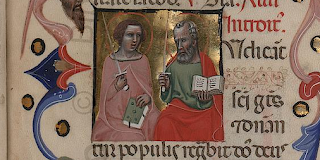

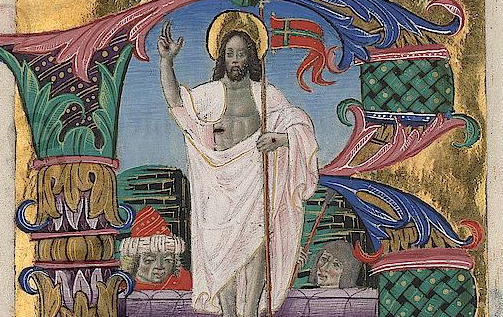

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.B.63, Bolognese missal, 14th century, with lustrous miniatures that are now attributed to a painter known as Pseudo-Niccolò. See his Risen Christ and an image described as defence of the book. See listing Ebner.

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.C.103

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.D.173, Augustine of Hippo?

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.D.200, Nicholas of Lyra’s Quaestio de Adventu Christi and Contra Judaeos

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.E.15

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.F.16, liturgical (Salerno Pontificale) with wonderful initials, including the sun and moon:

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.G.39

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.G.42

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.G.43, possibly the Elucidarium of Honorius Augustodunensis, 12th century

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.H.26, Chinese?

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.I.17, autograph? Gregory XVI (1837)

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.I.18.

- Borgh.14, liturgical

- Borgh.95, 14th century, legal, Arnoldus de Augusta

- Borgh.109, Thomas Aquinas, Summa

- Borgh.110, Thomas Aquinas, Summa

- Borgh.120, Thomas Aquinas, Quaestiones

- Borgh.154, Tancredus, 1185-1236, Opera, 13th-14th century

- Borgh.194, Tuscan translation of the poem De rerum natura by Lucretius (97-55 BC); check out the 2014 book by Ada Palmer on its influence in Renaissance Italy.

- Borgh.195, 18th-century European politics

- Borgh.230, Iohannes de Lignano, 1320-1383 Lectura super decretales

- Borgh.326

- Borgh.343

- Borgh.367, Il Governatore Politico e Christiano by Mezentius Carbonari

- Borgh.377, Scripturales

- Pal.gr.192, Hippocratic text

- Reg.lat.525, hagiography

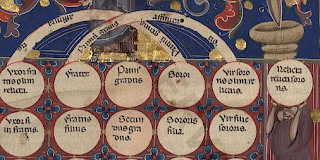

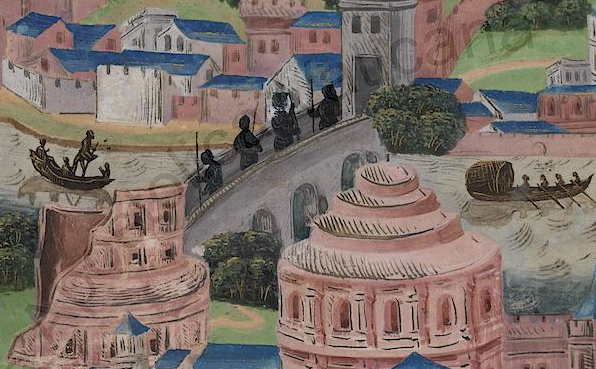

- Reg.lat.554, universal chronicle, description of Holy Land, copy of BN lat. 4892?

- Urb.ebr.3

- Urb.ebr.13

- Urb.ebr.32

- Urb.ebr.35

- Urb.ebr.36

- Urb.ebr.41

- Urb.ebr.42

- Urb.ebr.43

- Urb.ebr.44

- Urb.ebr.45

- Urb.ebr.48

- Urb.ebr.49

- Urb.ebr.50

- Urb.ebr.52

- Urb.ebr.53

- Urb.ebr.54

- Urb.ebr.55

- Urb.ebr.56

- Urb.lat.19, Psalter

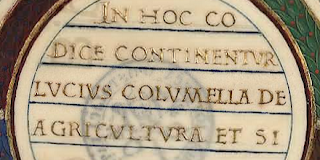

- Urb.lat.260, Columella's Roman-era treatise on agriculture (frontispiece below). This is one of about 40 copies deriving from Poggio Bracciolini's rediscovery of the work in Fulda, Germany, while he was in the north for the Council of Constance exactly 600 years ago. Poggio probably stole it, as it ended up in Milan in the early fifteenth century, where is it now Biblioteca Ambrosiana L.85 su; summary. At the end of the BAV copy is a fragment of Augustine, Retractationes.

- Urb.lat.348, Renaissance: poems, commentary on Horace: initial at the top of this post.

- Urb.lat.349, Homer in Latin

- Vat.lat.3836, Sermons of Augustine of Hippo, Leo the Great and others.

If you have corrections or additions, please use the comments box below. Follow me on Twitter (@JBPiggin) for news of more additions to Digita Vaticana. [This is Piggin's Unofficial List 5.]