Prohibemus etiam, ne sint equi lignei: sed si quis ex hac occasione vincitur, hoc ipse recuperaret: domibus eorum publicatis, ubi haec reperiuntur. (Text link.) Translation: We also prohibit (the game with) wooden horses; if any one loses in it, he may recover the loss. The houses of those where these games are played shall be confiscated. (English translation by Fred Blume: link.)Now plainly these wooden horses are not the sort used in the Greek capture of Troy, nor the sort that may have been vaulted over during Graeco-Roman gymnastic exercises. The museum has an online description of the item, which has exhibit number Ident.Nr. 1895, and a public image (bigger on the museum site):

The marble run or ball run in Berlin dates from about 500 and is a luxury stone-carved version of the machine. The marble is richly sculpted on the exterior with reliefs depicting the excitement of chariot racing: statues of horses, flute (aulos) players, men raising a banner, racetrack employees operating the draw for the teams and the start of a chariot race. The races appear to be conducted among teams of four horses, which was a passion among the people of Constantinople.

Jan Reichow refers to an account by the scholar Diether Roderich Reinsch and a museum guide by Arne Effenberger, quoted without page numbers or a proper bibliographic reference. The scholars appear to concur that the device was not a toy for a princeling but a capital investment for an entrepreneur in the equi lignei gambling trade, with the decoration on it conferring luxury and prestige, rather like the croupiers in casinos wearing tuxedos and bow ties to make the whole squalid experience seem as if it is high-class.

I made several marble runs from corrugated cardboard when I was about 10, and made another later as a father to amuse my sons. The frame was a cardboard carton and the tracks were strips of cardboard bent into V-cross-sections. With a box-cutter knife, I cut triangular holes in the carton to fit the tracks so that the marble could run through each track in succession. Children love marble runs, and this sort is easy to make and easy to recycle through the paper bank.

What makes a good marble run fun, until you have figured it out, is the unexpected way that the marble pops out on all sides of the block, rather like a mole showing up from a tunnel at an unexpected spot in my garden.

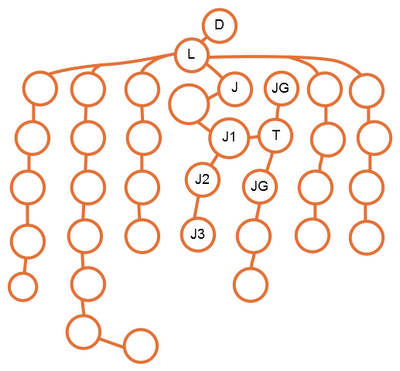

In my study of infographic history, the equi lignei device in Berlin firstly drew my attention because I wondered if its Late Antique users would have developed a scientific analysis of the path run through the device by the marble. An image on craft2eu.blog.de shows little holes at the side: it is not entirely clear if these are merely windows to show the players how far the marble has advanced or if these are exits for marbles that have been thrown out of the race:

Certainly some kind of mental projection of a path is a prerequisite for understanding a graph or a complex infographic like the Great Stemma.

The second aspect of interest is the illusionist potential of a marble run. Its operations are amusing because the marble can emerge, or at least be seen, where it is not expected. The marble seems to violate the rules of space by appearing magic-fashion in all sorts of unlikely places. It disrupts our sense of normal space. Some of the organization of the Great Stemma also breaks the rules of vision and is therefore slightly illusionist.

The marble run in Berlin at least confirms that the Late Antique world had a degree of experience with technical inventions that bent the rules of perception and vision when dealing with paths. This connects to the interesting technical guides by Hero of Alexandria including the one on ways to fake miracles in temples. These books were the subject of a post last year by Roger Pearse and there are links to the editions on the Wilbour Hall site.