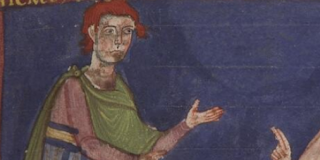

This codex featured last century in the Rome Reborn exhibition in the United States and is the dedication copy for Pope Nicolas V, actually depicting Trebizond (who was papal secretary) kneeling to present it to the pope. The bearded cardinal in pale blue in the image is Basilios Bessarion, also a Greek scholar from the city of Trebizond, who was George's arch-enemy on philosophical issues:

Both men had made it to the top in Rome by not being old Italian males, but minority candidates. It was a time when the papacy was eager to assert leadership over Greeks. George was an ardent Aristotelean, whereas Bessarion was a convinced Platonist. Their fierce battles and vituperation appear to have highly entertained 15th-century Rome. Check out Anthony Grafton's catalog for more.

The 64 new arrivals are documented on the old index page (which posts a total of 4,535 digitizations), but I was at first unable to actually examine them. None of the new arrivals was visible on the new public interface (which posted a total of only 4,307 as of June 8, 2016). The following full list was gradually annotated later.

- Borg.cin.403,

- Chig.R.V.29,

- Ott.lat.3124,

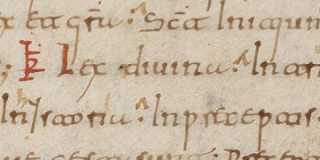

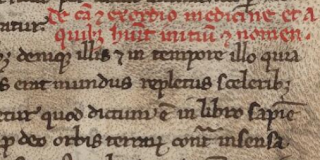

- Reg.lat.708, Venerable Bede, Eucherius of Lyon, Haimo of Auxerre with flyleaves containing some of Isidore, Sententiae, in Visigothic script (partly transcribed by Ullman and Brown:

- Ross.1169.pt.C,

- Vat.ebr.231,

- Vat.ebr.233,

- Vat.lat.107,

- Vat.lat.162,

- Vat.lat.364,

- Vat.lat.371,

- Vat.lat.372,

- Vat.lat.385, In evangelium s. Matthei commentarius by John Chrysostom, a Latin translation by George Trebizond (above).

- Vat.lat.472,

- Vat.lat.501,

- Vat.lat.549,

- Vat.lat.619,

- Vat.lat.620,

- Vat.lat.628,

- Vat.lat.629,

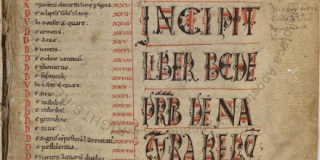

- Vat.lat.642, Bede, astronomy, but with no diagrams as far as I can see. This is a fairly important source of De natura rerum, De temporibus and De temporum ratione made in Lyon, France in about 1100, and includes the lunaria. Most of Bede's works are represented by many manuscripts, but this one, sometimes given the sign "V" is consulted for variations.

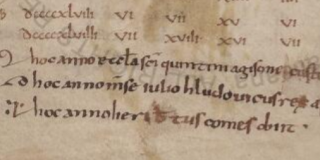

- Vat.lat.645, Twitter user @LitteraCarolina points out this chronicle contains entries at fol. 32v recording capture of Louis IV by (pagan) Normans and the death of Duke Heribert in 945–6.

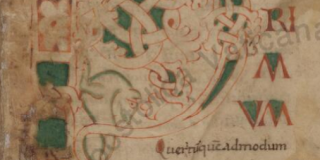

- Vat.lat.653, Haimo of Auxerre, commentary on the Epistles of Paul, in a hand described by Michael Gorman (2002) as romanesca (Lindsay's Farfa type). He writes: 11th century, from a monastery dedicated to Benedict and Scholastica, perhaps Subiaco. Gorman argues this was copied from a Vorlage from the Abbey of Monte Amiata in Tuscany. (Incidentally, the BAV bibliography only lists the Italian translation of Gorman's article, not the English original.) Here is part of the ornate initial P on fol. Ir:

- Vat.lat.657,

- Vat.lat.660,

- Vat.lat.662,

- Vat.lat.663,

- Vat.lat.666,

- Vat.lat.667,

- Vat.lat.668,

- Vat.lat.676,

- Vat.lat.677,

- Vat.lat.678,

- Vat.lat.682,

- Vat.lat.683,

- Vat.lat.688,

- Vat.lat.698,

- Vat.lat.702,

- Vat.lat.704,

- Vat.lat.710, Albertus Magnus, Summa

- Vat.lat.714,

- Vat.lat.720,

- Vat.lat.728,

- Vat.lat.734,

- Vat.lat.736,

- Vat.lat.737,

- Vat.lat.746.pt.1, Thomas Aquinas, Summa, part iii

- Vat.lat.746.pt.2,

- Vat.lat.750,

- Vat.lat.755,

- Vat.lat.756,

- Vat.lat.757,

- Vat.lat.3195, Petrarch, incipit "amor piangena ..."

- Vat.lat.5029, Cristobal de Cabrera, 1513-1598: De excellentia et mirabilibus altissimi Sacramenti Eucharistiae

- Vat.lat.6069, master illuminations like this on folio 43r

- Vat.lat.7618,

- Vat.lat.8205,

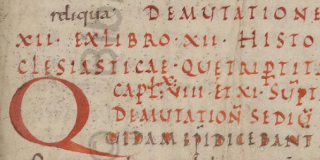

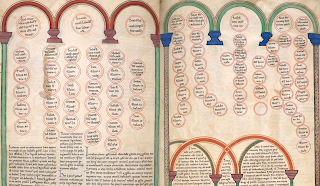

- Vat.lat.8523, fine gospels book with these canon tables:

- Vat.lat.9327,

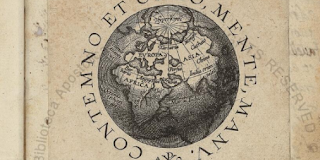

- Vat.lat.9385, Tasso, with this fine engraving of the globe by Abraham Ortelius at folio 18r

- Vat.lat.9972, heavily annotated Tasso incubable

- Vat.lat.10477, Catalog of the library of Pope Clement XI.

- Vat.lat.10485, Further listings concerned with the same library

- Vat.lat.10999, Lives of Saints