Here is how the artist fancied Pliny in expository mode:

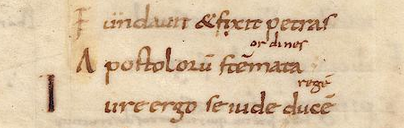

Also new is Vatican Vat. lat. 3375, a late sixth-century Neapolitan codex excerpting the works of Augustine of Hippo. It is acopy in half-uncial of an anthology that had been composed just a generation earlier by Eugippius of Naples and is an important link to Christian culture at the end of late antiquity.

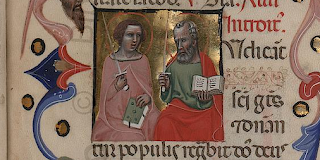

We also have what looks like a couple of chaps with paunches, receding hippie hairlines, and glass steins in the hand. But I am guessing they are actually sirens. They appear in Barb.lat.409, which is a liturgical office for the feast day of King Louis of France (1214-1270), after he had been made a saint.

A further portolan chart, Borg. Carte. naut. V, is in this batch, but sadly the resolution is so low that it is impossible to read the text. Reader Jens Finke points out that a just-about-readable black-and-white image of this appeared in Heinrich Winter, "The Fra Mauro Portolan chart in the Vatican" (Imago Mundi, 16 (1962), pp. 17-28, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1150299.)

Here is the full list:

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.A.32

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.C.98

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.D.157

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.D.169

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.D.193

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.E.33

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.F.27

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.G.3

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.G.54

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.H.52

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.K.1

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.K.2

- Barb.lat.409, liturgical office for feast of Louis IX of France, image above

- Barb.lat.679, a compilation of canon law, with a folio about the Council of Carthage of 390 CE (summary)

- Borg.Carte.naut.V, illegibly digitized portolan chart, see above

- Borgh.22

- Borgh.43

- Borgh.53

- Borgh.91

- Borgh.93

- Borgh.99

- Borgh.104, 14th century codex of Petrus de Ilperinis, Tractatus de praedestinatione

- Borgh.113

- Borgh.127

- Borgh.143.pt.1

- Borgh.145

- Borgh.155

- Borgh.168

- Borgh.176

- Borgh.180

- Borgh.201

- Borgh.207

- Borgh.215

- Borgh.238

- Borgh.251

- Borgh.257

- Borgh.281

- Borgh.301

- Borgh.305

- Borgh.310

- Borgh.313

- Borgh.334

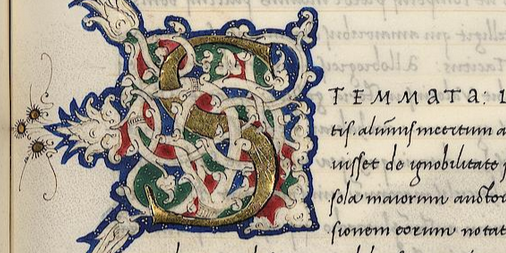

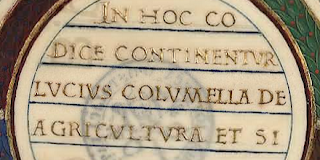

- Borgh.369, Pliny's Natural History

- Borgh.384

- Borgh.387, anonymous compilation of rules and figures of geometry (ff. 1-27)

- Cappon.1

- Cappon.2

- Cappon.3

- Cappon.8

- Cappon.10

- Cappon.11

- Cappon.16

- Cappon.19

- Cappon.20

- Cappon.21

- Cappon.22

- Cappon.23

- Cappon.25

- Cappon.36

- Cappon.37

- Cappon.38

- Cappon.40

- Cappon.49

- Ott.lat.356

- Reg.lat.1484

- Vat.ebr.119

- Vat.ebr.130

- Vat.ebr.143

- Vat.estr.or.4, Latin-Chinese dictionary

- Vat.estr.or.8,

- Vat.estr.or.40, panorama painting of qinqming festival

- Vat.estr.or.64.pt.2,waterfall drawing

- Vat.estr.or.83,

- Vat.estr.or.85, Sinhalese

- Vat.estr.or.86,

- Vat.estr.or.97,

- Vat.estr.or.99,

- Vat.estr.or.101,

- Vat.estr.or.114,

- Vat.estr.or.117,"Cahier siamois", only the container!

- Vat.estr.or.118, ditto

- Vat.estr.or.147.pt.1.2,

- Vat.estr.or.147.pt.6,

- Vat.estr.or.156, folder of ink sketches, whereby Twitter user @MareNostrum2 points out that Digita Vaticana has (inadvertently) digitized a page from a 1909 Japanese newspaper with it: was this used as wrapping material to send the item to Rome?

- Vat.estr.or.159, 19th century (?) Japanese drawings

- Vat.gr.180

- Vat.lat.3375, excerpts from Augustine (see above)

- Vat.turc.50

That makes 88 in all. Please add any contributions by way of the comments pane below. [This is Piggin's Unofficial List 9.]