An ink rubbing was made from the stele in the 1630s and sent to Rome, and the discovery caused a sensation in Europe, where Chinese adoption of Christianity in 631 had been entirely unknown, as Anthony Grafton's Rome Reborn page (with a false callmark) notes.

The rubbing, now part of the bundle Barb.or.151, is one of the oriental treasures that has just been digitized by the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, posted online on April 21.

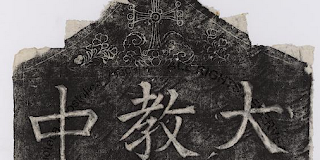

The monument is about 2.5 metres tall and capped by a carved cross. The heading, as translated in the Wikipedia entry reads, "A Monument Commemorating the Propagation of the Ta-Chin Luminous Religion in the Middle Kingdom". Ta-Chin is an old Chinese term for the Roman Empire.

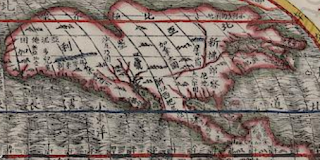

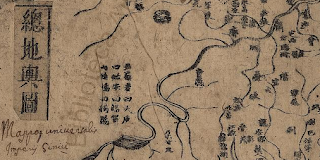

Another item in this package of digitizations is an abridgement printed in the 1620s of the famed map of the world that Matteo Ricci, the first Jesuit missionary to become adept in Chinese, had produced in 1574. The hand-tinted print was made at the orders of Giulio Aleni, whose name is marked on it, as Grafton notes. Here is North America:

Also in the bundle is the printed astronomy, Chien-chien tsung-hsing-t'u by Adam Schall von Bell, of which Grafton notes: von Bell introduced the new astronomy of Galileo, including the telescope, to China. This single-sheet printed map with explanatory text shows the stars visible in the sky of northern China.

- Barb.or.151.pt.1, bundle of Chinese materials (above)

- Borg.cin.497,

- Borg.cin.537,

- Borg.cin.538,

- Borg.gr.27,

- Ott.lat.1252,

- Ott.lat.2358,

- Reg.lat.165,

- Reg.lat.179,

- Reg.lat.1935,

- Reg.lat.1995, the autobiography of Pope Pius II, the former Enea Silvio Piccolomini. This book, the Commentarii, is a remarkably frank autobiography and the only book he wrote after his election, in which he put his passions and prejudices on full view, Anthony Grafton notes in the Rome Reborn catalog. Enea Silvio was the first humanist to be elected to the papacy.

- Reg.lat.2039,

- Ross.184,

- Ross.254,

- Ross.276,

- Ross.616,

- Ross.701,

- Ross.977,

- Ross.1165,

- Urb.lat.252,

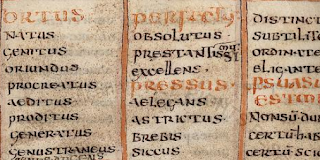

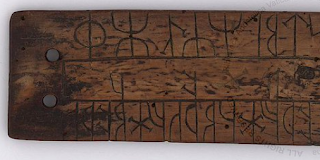

- Urb.lat.293, a nicely written 11th or 12th century manuscript of Vitruvius on Architecture notable for its two flyleaves, now folios 96 and 97, which date from the first half of the 8th century and contain important material from the late antique Greek medical writer Oribasius: This contains words glossed in Old German, indicating it has a German provenance: Lowe number CLA 1 116, see Trismegistos:

- Urb.lat.367,

- Urb.lat.378,

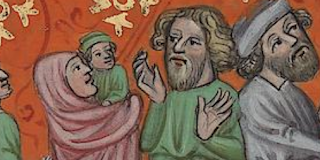

- Urb.lat.548, a very fine Renaissance part-bible transcribed by Mattheus de Contugiis, here the start of Proverbs, showing Solomon learning wisdom from father David:

- Urb.lat.597,

- Urb.lat.644,

- Urb.lat.1030, a Pietro Bembo autograph

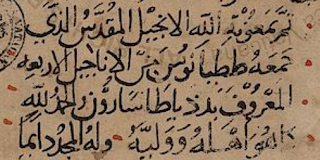

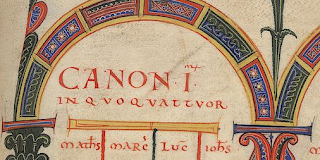

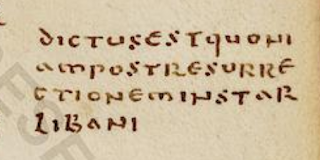

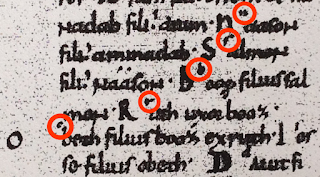

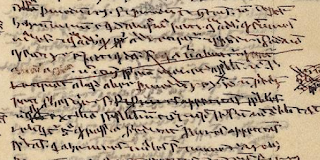

- Vat.ar.14, a 12th-century Arabic translation of the Diatessaron of Tatian, a combination of all four gospels into a single narrative. Thanks to Adam Carter McCollum in Vienna for pointing out this one on Twitter. Here is the colophon:

- Vat.ar.503,

- Vat.ar.581,

- Vat.ar.1606, a tiny and very ancient book in Arabic, apparently selections from Koran

- Vat.ebr.123,

- Vat.ebr.142.pt.2,

- Pal. lat. 381 Ovidius Naso, Publius; Cicero, Marcus Tullius: Sammelhandschrift (Deutschland (Heidelberg?), 15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 733 Digestum vetus (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 734 Digestum vetus (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 735 Digestum vetus (13. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 736 Digestum vetus (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 687 Egidii (de Foscariis) ordo iudiciarius editus secundum consuetudinem bononiensem in foro ecclesiastico approbatam ; Mag. Bartholomei Brixiensis questiones dominicales et venales de iure canonico (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 691 Monaldi (Iustinopolitani ord. fr. minorum) summa iuris canonici (15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 695 Fratris Monaldi summa de iure canonico secundum ordinem alphabeti (14. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 1525 Cicero, Marcus Tullius: Opera ; Orationes (Deutschland (?), 15. Jh.)

- Pal. lat. 1834 Melanchthon, Philipp; Luther, Martin; Erasmus, Desiderius: Epistolae (Wittenberg, 1536-1543 (?))