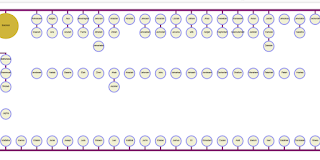

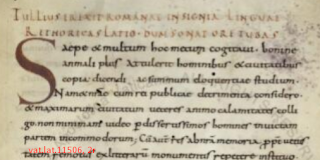

Here is how it is done in the fifth century in the Great Stemma, with a track at top representing kings of Judah, at centre kings of Samaria and below it, the ancestors listed by the Gospel of Luke:

It is helpful here to use certain fundamental cognitive distinctions laid out by Rafael Núñez and Kensy Cooperrider not long ago in a review paper.

Humans can use (abstract) space to map the passage of time in three distinct fashions in their gesture and speech: projecting deictic time (from where "I" stand), setting an order of events in sequence time (distinguishing the placement of "landmarks" in time), and comparing one or more temporal spans. Scholarly discussions of time sometimes muddle these. As two authors remark:

Philosophers, physicists, and cognitive scientists have long theorized about time –along with domains such as cause and number – as a monumental and monolithic abstraction. In fact, however, the way humans make sense of time for everyday purposes is, as in the case of biological time tracking, more patchwork.There is no reason to suppose that this typology in the mind transfers easily to a drawing. In fact, the two authors point out that investigating space-time mappings in non-English-speaking cultures by asking people to demonstrate with cards and paper may be handicapped by the fact that this "material realization " needs to itself be learned first:

... arrangement tasks are not well-suited for use in such populations, because they presuppose familiarity with materials and practices that, in fact, require considerable cultural scaffolding.A similar point was made 20 years ago by Mary Bouquet, who rebuked anthropologists for asking Portuguese people unfamiliar with stemmata to draw their kinship bonds this way.

So what are the tracks in the Great Stemma doing? They don't tell us anything about the Latin concept of deictic time (though that has been very expertly figured out by Maurizo Bettini, who shows the Romans faced the past with their backs to the future), whereas the three tracks seem to demonstrate a Latin tendency to set out a sequence of time from left to right, in accord with the Latin writing system, and they do indeed suggest that Latin-speakers would have compared durations of temporal spans in a spatial way when speaking of them.

It could well be argued that the invention of this type of timeline was inspired by gesture, though I have considered other origins such as game-play. The spans are not exactly calibrated with one another, but match one another in lengths more precisely than a speaker would ever intend to do in gesture.

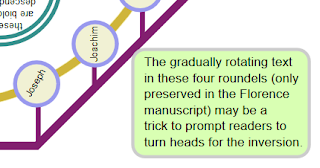

An intriguing aspect of the Núñez and Cooperrider paper is its mention of the spiral of time perceived in some cultures. The Great Stemma might have something going on in this respect where it loops up at the end and flips, with the script gradually rotating and terminating in a plaque with several upside-down sentences:

These are all aspects that require further study and analysis.

Bettini, Maurizio. Anthropology and Roman Culture: Kinship, Time, Images of the Soul. Translated by John Van Sickle. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1991.

Bouquet, Mary. ‘Family Trees and Their Affinities: The Visual Imperative of the Genealogical Diagram’. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 2, no. 1 (1996): 43–66. doi:10.2307/3034632.

Núñez, Rafael, and Kensy Cooperrider. ‘The Tangle of Space and Time in Human Cognition’. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17, no. 5 (2013): 220–29. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.03.008.