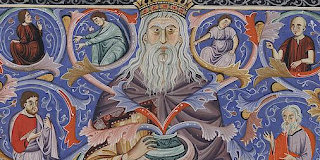

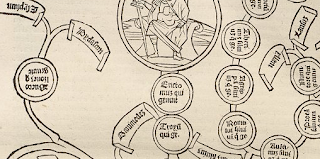

Known as the Codex Benedictus, this great work came online at Digita Vaticana on January 18. It was created for use on the feasts of saints Benedict, Maurus (Benedict's first disciple) and Scholastica (Benedict's sister). At Montecassino, they could not point to an actual tomb of Benedict, but they insisted he lay somewhere in the abbey precincts.

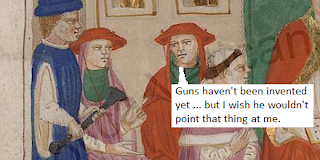

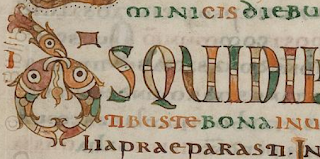

The making of the codex, which features 66 large and colourful miniatures of Benedict's life, was supervised by Abbot Desiderius (1058-1086) who composed part of the text and had himself pictured on the dedication page, folio IIr, handing over this tribute to the long-dead Benedict himself. An inscription reads: Cum domibus miros plures pater accipe libros.

Among the scenes is Benedict showing to a younger monk, Servandus, the world from a high tower as angels fly past the window carrying the soul of a bishop, Germanus (folio LXXIVv). This is a re-interpretation of Benedict's often-quoted dream of having seen the world from a heavenly perspective, which can be read in Gregory the Great's Dialogues 2.35.

Gregory puts an interpretation on Benedict's report of viewing the "whole world" from the tower which Patrick Gautier Dalché considers tantamount to a Late Antique theory of visualization:

The soul of him who sees in this manner is above itself; for being rapt up in the light of God, it is inwardly in itself enlarged above itself, and when it is so exalted and looks downward, then it comprehends how little all that is, which before in former baseness it could not comprehend. (Gardner translation).On folio LXXXr is an image of Benedict's Entombment (below). The codex, which also contains texts by Alberic of Montecassino, features many smaller details and initials.

An elaborate facsimile of it was published in 1981 as an expensive collectible. Now you can enjoy it for free. For a comprehensive and excellent introduction to the codex and these images, read John Wickstrom's 1998 article, Pope Gregory's Life of St. Benedict and the Illustrations of Abbot Desiderius of Monte Cassino, on Academia.edu.

Digita Vaticana's new posted total of manuscripts after the 55 uploads on January 18, 2016 is 3,549. The secret list of new arrivals (which I compiled using spot-the-difference software) is below, whereby I will leave the Pal.lat. series undiscussed, as they have been public in Germany for some time.

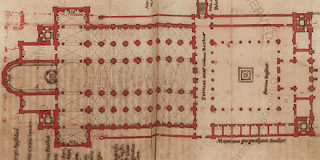

- Barb.lat.4409, architectural drawings of the Vatican by Domenico Castelli

- Borgh.280, Anonymous: Summarium sive Breviarium super Decretum, 14th century

- Cappon.313.pt.A, architectural engravings of Rome

- Pal.lat.636,

- Pal.lat.697,

- Pal.lat.943,

- Pal.lat.944,

- Pal.lat.945,

- Pal.lat.947,

- Pal.lat.948,

- Pal.lat.949,

- Pal.lat.959,

- Pal.lat.960,

- Pal.lat.961,

- Pal.lat.964,

- Pal.lat.968,

- Pal.lat.981,

- Pal.lat.982,

- Pal.lat.983,

- Pal.lat.984,

- Pal.lat.985,

- Pal.lat.986,

- Pal.lat.988,

- Pal.lat.1060,

- Pal.lat.1094,

- Pal.lat.1098,

- Pal.lat.1102,

- Pal.lat.1112,

- Pal.lat.1113,

- Pal.lat.1136,

- Pal.lat.1181,

- Pal.lat.1202,

- Urb.lat.92, Bernard of Clairvaux's letter against Peter Abelard

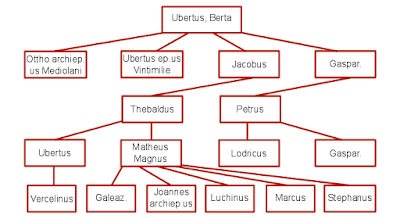

- Urb.lat.155, civil law commentary by Roffredo Epiphanius and Bonaguida

- Urb.lat.167, William Durandus and Bartolus de Saxoferrato

- Urb.lat.177, Roland Passagerus

- Urb.lat.184, Aristotle, Physics, etc.

- Urb.lat.236, Galen, Avicenna, etc, in a 14th-century manuscript

- Urb.lat.275,

- Urb.lat.288,

- Urb.lat.301, a revision of Cornucopia, a mid-15th century commentary on Martial by Niccolò Perotti. This featured in the Rome Reborn exhibition in the mid-1990s in the United States, where Anthony Grafton's catalog notes: Later the work was revised and expanded by Perotti's son Pyrrhus.

- Urb.lat.311,

- Urb.lat.319, Cicero, 15th-century ms.

- Urb.lat.321, ditto

- Urb.lat.331, Petrarch, 15th-century ms.

- Urb.lat.332, ditto

- Urb.lat.333, ditto

- Urb.lat.334, Petrarch, De remediis utriusque fortunae

- Urb.lat.343, Plautus, comedies

- Urb.lat.355, Seneca, tragedies

- Urb.lat.356, ditto

- Urb.lat.368, anthology of poetry and fables, 15th century, full contents copiously listed by Stornajolo's catalog

- Urb.lat.373, poetry by Porcelli and others, 15th century

- Urb.lat.402, writings by Piccolomini before he became Pope Pius II, 15th century

- Vat.lat.1202, the Codex Benedictus (above)

If you have corrections or additions, please use the comments box below. Follow me on Twitter (@JBPiggin) for news of more additions to Digita Vaticana. [This is Piggin's Unofficial List 36.]

Gautier Dalché, Patrick. “L’Héritage Antique de Cartographie Médiévale: Les Problèmes de les Acquis.” In Cartography in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: Fresh Perspectives, New Methods, edited by Richard J. A. Talbert and Richard Watson Unger. Leiden: Brill, 2008.