Portolan charts are, for all intents and purposes, the first true western maps. Everything that precedes them, ought, in my view, to be classed as geographical diagrams.

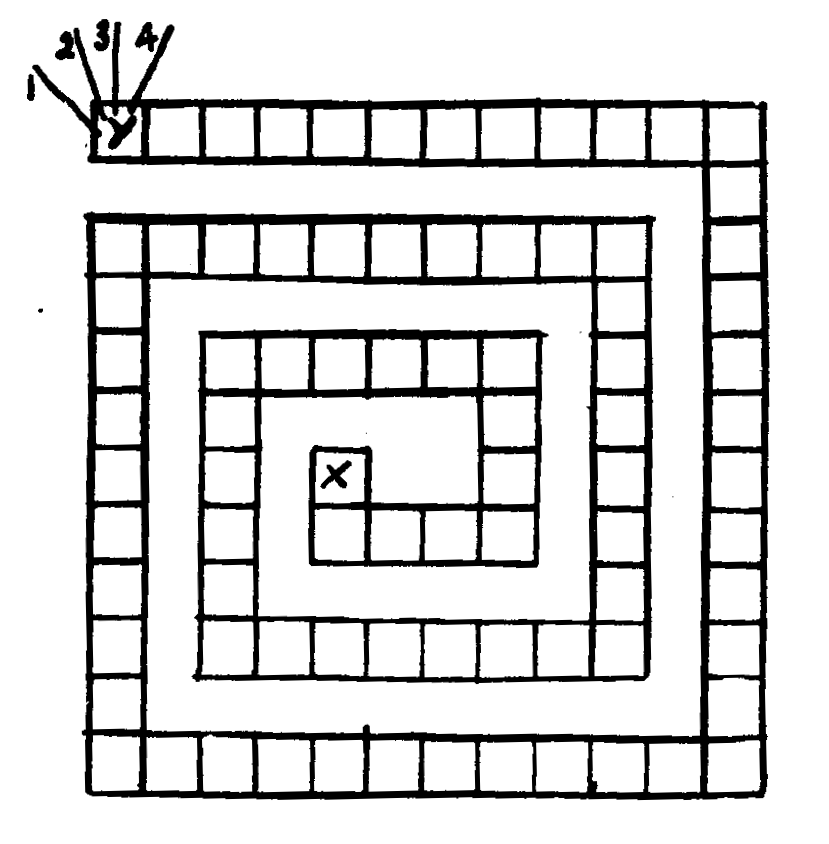

A portolan chart was something novel and unprecedented, showing the world deskewed and to scale. Geographical diagrams like the BL's Psalter Map of 1265 (see this flash version) showed the human world as mentally represented. By contrast, portolan charts, with compass lines superimposed, show the physical world as one navigates it, with the entire coastline of a sea fully labelled without regard for the social standing of the places on the coast. When a vessel is trapped by a landward wind, any of the places here offers a potential haven on a lee shore. The Vat. lat. 2972 codex contains an atlas of five sheets and is part of Marino Sanudo's Liber secretorum, a book devoted to a mad plot to destroy the Muslim world. Here is the atlas version of the English Channel (folio 110v):

In the middle you see Dumqerqo (Dunkirk), Gravallinga (Gravelines), Calles (Calais) and Bellogna (Boulogne), and at right Parissius (Paris) and Cam (Caen).

Tony Campbell, former map librarian of the British Library, wrote a fine descriptive summary about portolan charts earlier in February on the Pelagios blog while presenting the portolan component of the Pelagios project. He tells us at least one portolan chart from the very end of the 13th century survives. The BAV's, from just two decades later in 1320, will likely become a prime reference on the internet. Yale has a later chart from 1403 online.

Curiously, Genoa-born Vesconte also did mappaemundi similar to that in the Psalter Map. He was on the cusp of the transition from old to new. Here are the British Isles in his Vat. lat. 2972 mappamundi. Since this map (112v) has east at its top, Ireland (Ybernia) is at the bottom of this grouping:

Update

I have tried to tag all the places on the continental coast in the portolan chart above, but some defeat me. Here is what I have resolved, after consulting Campbell's general toponymic listing:#Bruges

? (Cavo Sta Catalina identified as Pointe de Zand by Campbell. Not clear what St Catherine's; the source document would have been Portuguese.)

#Oostende

#Nieuwpoort

#Dunkerque

#Gravelines

#Calais

#Wissant

#Boulogne

#Étaples

? (vapa identified by Campbell as Port St. Quentin or Eu.)

#Dieppe

#Fécamp

? (no port marked; Campbell proposes Chef de Caux)

? (no port marked, so "loira" may be an inland place)

#Quillebeuf

#Harfleur (on wrong side of Seine!)

#Honfleur

#Touques

#Caen

#Ouistreham

Some of these ports no longer exist, the rivers having later silted up and become unnavigable, leaving coastal areas that today are mainly a zone of holiday beaches.

Tony Campbell published a major new article on March 2, 2015 on the Carte Pisane, which is traditionally regarded as the oldest portolan chart, but is now the focus of controversy. He sets out arguments as to why it should be dated to the very end of the 13th century.