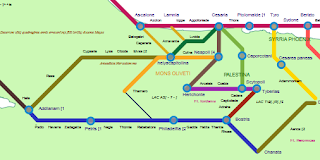

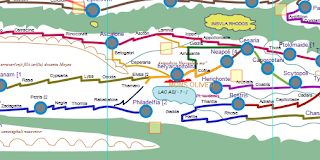

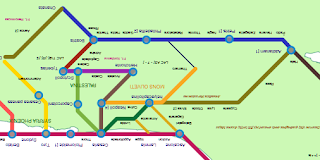

The Madaba Mosaic Map in Jordan has never, to my knowledge, been reproduced and published to modern scholarly standards, frustrating my efforts to include it in the

Library of Latin Diagrams.

The first photographs, by Eugène Germer-Durand, appeared in 1897 in a thin book in Paris. The mosaic in color photographs appeared in

Herbert Donner and Heinz Cüppers (1977), but the images are single, poorly lit and not coordinated.

It ought to be possible to sythnesize one composite, high-contrast, high-resolution photograph of the whole artefact in the Church of St George in Madaba (a single exposure of the entire map is impossible to take, since the mosaic flows on all four sides around a pillar).

However a photograph does not allow a diachronic approach where we can contemplate the object at different times. Parts of the mosaic have disappeared in the past century.

What is required is a highly zoomable technical drawing as a base for annotation.

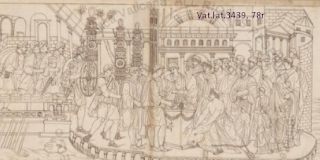

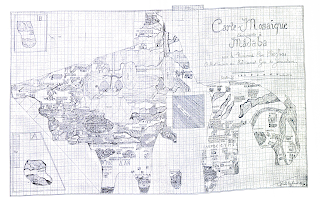

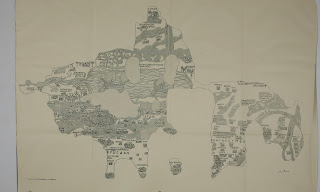

Astonishingly, scholarship continues to mostly depend on a colored drawing made of the mosaic at the turn of the century by Paul Palmer, a Jerusalem architect. That drawing is employed in the still-current edition of the map by the late Mikael Avi-Yonah of 1953. At my prompting, a major library earlier this year brought the first printed book with the drawing online (

see my post), but I soon realized it is neither practical nor economical to digitize the Palmer drawing at fine resolution. What other drawings exist?

As far as I know, most of the drawings date from the early years. Some 20 years ago, Yiannis Meimaris of the National Hellenic Research Foundation surveyed some of them.

The first drawing, on graph paper, was that by Cleopas Koikylides, a scholar but not an archaeologist, of 1896 December 13. This was published 1897 March 8 in his pamphlet printed by the Franciscan Fathers and is reproduced in the volume by Donner/Cüppers, but it is too crude to be useful.

The next drawing was done by Geōrgios Arvanitakis, variously described as the Greek Orthodox patriarchal astronomer or professor of the Holy Cross School of Theology in Jerusalem, who did a more thorough version at Madaba 1897 January 9-23. Meimaris describes this as a precise copy in 12 sheets on a scale of 1/5. The same copy

included an 0.80 x 0.60 m plan of the church, showing the position of the mosaic

in it, but excluded the two fragments which were separated from the main part of

the map and located to the north of it.

Arvanitakis tried to wring the maximum money value from his work. He photographed

his own drawings and offered reproductions for 100 golden franks. This

seems to be the set of 10 photos mentioned by Peter Thomsen in the other major history of the drawing period. Arvanitakis also prevailed on the Franciscans help him in a bid to sell his original to French scholarly bodies (Meimaris quotes Clermont-Ganneau PEFQSt 1897:213-214 and I have also found a report about this in

Belles-Lettres). Hopping promptly on a ship to Istanbul, he gave lectures about the map. The newspaper

Neologos Konstantinoupoleos reported these

seances in March.

Donner/Cüppers prints a rough drawing of 1897 attributed to Enrico Stevenson and published with an article, "Nuove scoperte a Madaba nella Palestina" (

NBAC 3, 325).

In 1898 a patriarchal letter of authority was issued to Mr. Salim (K)ari. From a copy of the map in the possession of the Palestine Exploration Fund, on which is written that "it was bought from Selim el-Kary who said he copied it direct from the mosaic". I have not seen this image published anywhere.

In September 1901, the Orthodox Patriarchate seems to have engaged two German painters, F. Cornely and G. Hartmann, to paint a full-size copy on canvas of the mosaic. Thomsen wrote in 1929 that this was still hanging in the Greek School opposite the Greek Hospital. Meimaris says it was then lost for several decades and it "was found only recently (in November 1996) by me in the Patriarchate, torn into two pieces and in extremely bad condition. This copy deserves to be restored, since it is the only life-size colour reproduction of the original map." No more has been heard of it.

Palmer, who had been given authority by the Greek patriarch February 20,1897 to examine the map, may not have done a precise copy at first. Wilhelm Kubitschek, in a Vienna lecture on January 7, 1898, quotes from the newsletter, the

Mittheilungen, of the Deutscher Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas (DVEP) dated April 18, 1897, stating that scaffolding was erecting the church for photographs to be taken for Palmer, but that the images turned out to be unusable.

"Die beiden genannten Herren (Palmer and Hermann Guthe from Berlin) sind nun damit beschäftigt, eine in Farben ausgeführte Zeichnung der Karte herzustellen," he added. Kubitschek's grumbling was justified. It was not until April 1904 (according to Thomsen) that

Guthe, who was to write the accompanying text, arrived in Jerusalem to inspect his accuracy.

What happened next is unclear. By Palmer's own account, he teamed up four years later with Cornely and Hartmann, but there remains a certain suspicion that he may have saved himself trouble by copying their image, at least in part. Thomsen conversely implies that the two copied from Palmer:

Die weitgehende Übereinstimmung mit den Tafeln von Palmer erklärt sich daraus, daß die beiden Maler mit ihm zusammen gearbeitet haben.

This colored drawing was finally published in ten lithographs in 1906 and presumably owes something to Cornely and Hartmann, whose first names I have not been able to discover. They are real enough people though, gaining parallel mention by Josef Strzygowski and P. J. Dashian

in connection with a mosaic of Orpheus in ZDPV (1901) and by Metaxakis in

Nea Sion (1906, 156). Thomsen notes several points where Palmer's accuracy is wanting:

Bei Palmer sind die Farben

viel zu lebhaft für das im allgemeinen matt gehaltene Original. Die Linien der

einzelnen Steinchen sind zu regelmäßig gezogen. Spätere Ausbesserungen und

Schäden sind nicht erkennbar. Das Versehen an den drei Toren der Grabeskirche

(gleichhoch und oben gerundet) ist in der endgültigen Ausgabe berichtigt.

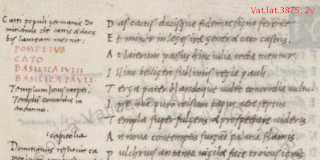

Our immediate need now is for a crisp drawing which covers every detail of the mosaic, but is not overly complex. For that I intend to turn elsewhere, to a line drawing published by Adolf Jacoby in 1905. It is a simple tracing of the photographs in the Germer-Durand book by an amateur in Strasbourg, Leutnant Brix.

Jacoby does not give Brix's first name but says he had been an army munitions disposal officer, presumably Prussian. Brix probably never saw the mosaic in color let alone travelled to Madaba, but his evident training in technical drawing from black and white photographs and patient tracing at least gives us a place to start creating a scalable vector graphics image which can be modified as we go along.

Avî-Yônā, Mîḵā’ēl. The Madaba Mosaic Map: With Introduction and Commentary. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1954.

Donner, Herbert, and Heinz Cüppers. Die Mosaikkarte von Madeba: Tafelband. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1977.

Germer-Durand, Eugène. La Carte Mosaïque de Madaba: Découverte Importante, 1897. Paris: Maison de la bonne presse, 1897.

Jacoby, Adolf.

Das Geographische Mosaik von Madaba: Die Älteste Karte des Heiligen Landes ; Ein Beitrag zu ihrer Erklärung. Studien über Christliche Denkmäler 3. Leipzig: Dieterich, 1905.

Kubitschek, Wilhelm. “Die Mosaikkarte Palästinas.” Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft 43 (1900): 335–80. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924094297904.

Meimaris, Yiannis. “The Discovery of the Madaba Mosaic Map. Mythology and Reality.” In

The Madaba Map Centenary, 1897-1997: Travelling through the Byzantine Umayyad Period; Proceedings of the International Conference Held in Amman, 7-9 April 1997, edited by Michele Piccirillo. Publications of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum [Collectio Maior] 40. Jerusalem: Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, 1999.

https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://www.christusrex.org:80/www1/ofm/mad/articles//*.

Palmer, Paul, Hermann Guthe, and Deutscher Verein zur Erforschung Palästinas.

Die Mosaikkarte von Madeba. Leipzig, Baedeker, 1906.

http://archive.org/details/diemosaikkartevo00deut.

Thomsen, Peter. “Das Stadtbild Jerusalems auf der Mosaikkarte von Madeba.”

Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 52, no. 2 (1929): 149–74.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27929765.