This was the week when the Vatican's library, the BAV, made available online digital images of what is perhaps the world's oldest intact, large, bound book, the Codex Vaticanus. It contains a handwritten text on 759 vellum leaves and is generally estimated to have been made in the second quarter of the fourth century (325–350 CE).

That it survives is amazing. That no one noticed what the Vatican was doing is almost more amazing. But more about that later.

During the 19th century, the BAV customarily only allowed visitors to touch this treasure under guard, so great was the fear that it would be stolen or damaged by a religious fanatic. Scholars grumbled at this, but the librarian's suspicions were not ill-founded. That anybody with web access can now read it without a couple of muscular young clergymen staring at the back of their neck as if they were a terrorist is a wonderful transformation.

The codex contains the Christian Old and New Testament in Greek and is comparable in age and significance with the Codex Sinaiticus, which got its own lush online presentation five years ago.

One can toss up as to whether the Vaticanus or the Sinaiticus is the oldest substantial bound book in existence, but the Vaticanus is the one in better shape, since it is still in one binding. The Sinaiticus got dismembered in the 19th century by the sort of scholar that the Vatican wisely never trusted (see above) and is now divided between four countries.

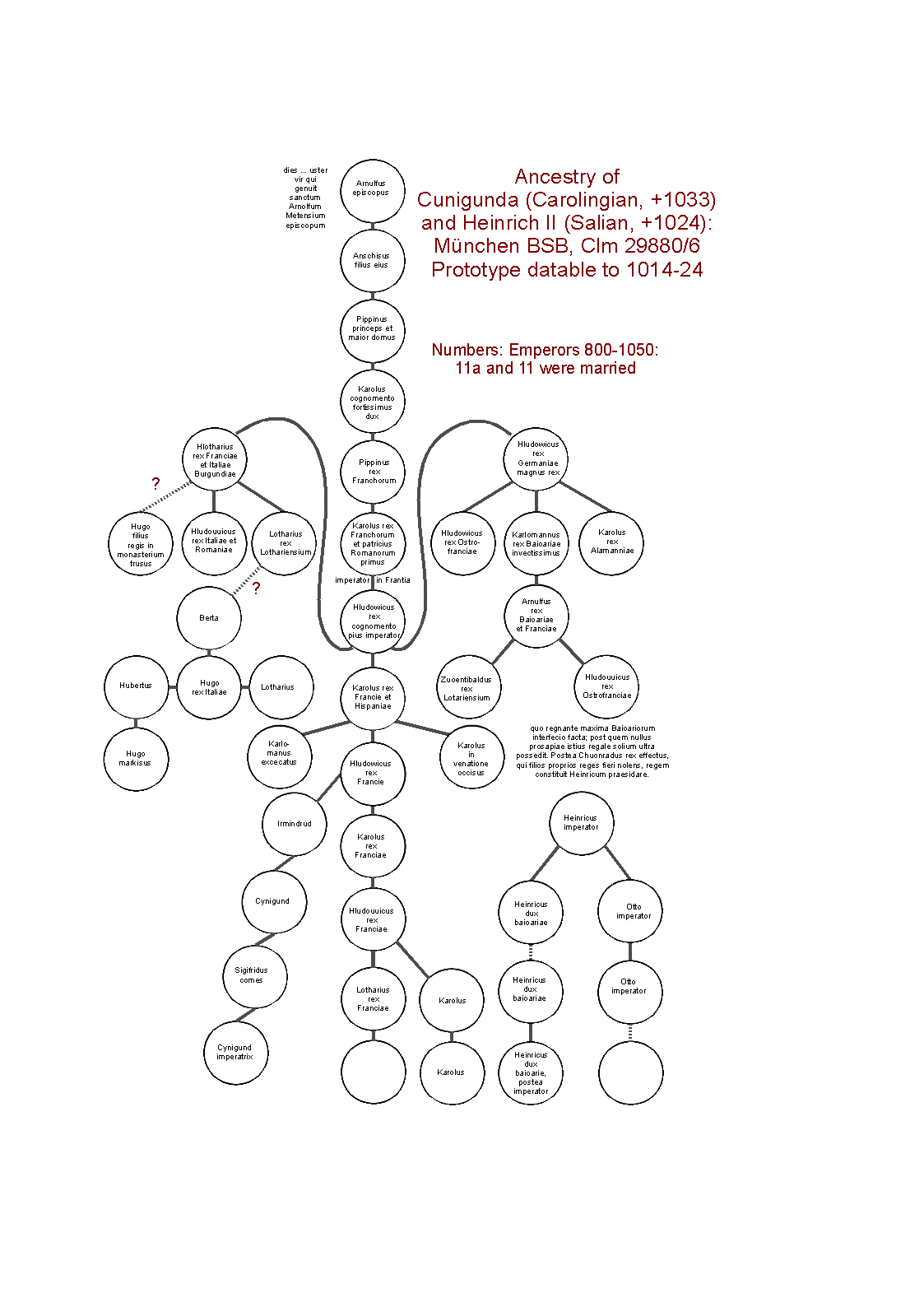

Neither book has a production date on it, so their ages can only be guessed from palaeographic evidence. Wikipedia's substantial description argues Vaticanus contains more

antiquated features and is the older of the two, although one scholar, T.C. Skeat, propounded a theory that the two codices are contemporary and both come from the Late Antique scriptorium of Eusebius of Caesarea.

At the start of this post, I said the codex may be the oldest bound book. The qualification is important since books as we now know can come in three forms: scroll, codex and e-book.

I would have seen my first e-book at the Frankfurt Book Fair about 30 years ago and thought it a strange new thing, and the first owner of the Codex Vaticanus might have seen his first codex used for a scholarly purpose and thought it was a strange thing 30 years before he commissioned this very special codex for himself.

It is generally suggested that codices -- that is, books made of flat pages between two boards, bound at a spine -- began to outnumber the earlier technology, the scroll, in about 300 CE.

So "books" older than the Codex Vaticanus do survive: in scroll form, or as isolated pages torn from codices, among them the Chester Beatty papyri. But if you were to ask me where to find the world's oldest book -- meaning a thing between two covers, which is what most of us would mean -- I would point you to Rome, BAV, Vat. gr. 1209. Look at it and marvel.

On February 16, 2015, the BAV added 31 new items to its stock of online digitizations, raising the total volumes so far to 1,626. The collections added to were Arch. Cap. S. Pietro (10), Borgh. (5), Ott. lat. (1), Sbath. (1), Vat. ebr. (6), Vat. gr. (1, the Codex Vaticanus), Vat. lat. (4) and Vat. turc. (3).

Items in the enormous Vat. lat. series which are newly available are Vat. lat. 83, which is a fine collation of hymns and psalms from the 11th century. It has a wonderful illumination in it of David with harp and the other supposed writers of the psalms, among them Ethan in a sailor suit (right), each with quill and ink-horn and a nifty little mobile desk of the sort that court writers must have used in the 11th century.

Tracking down the psalm authors had always been a matter of interest to Jewish and Christian scholars as we know from my edition of the fifth-century Liber Genealogus.

Also online for the first time are a book catalogue (Vat. lat. 3970) by Cardinal Sirleto (1514-85), a biography of Saint Gerard (Vat. lat. 7660), and a wonderful scrapbook of fragments (Vat. lat. 13501) presumably extracted from old bindings where we see a great variety of writing styles, a palimpsest or two, bits of sheet music and everything else that would have been hurled out in library spring cleanings and landed in this or that medieval book binder's recycling bin.

Sadly, the Vatican Library does not have the time or resources to promote this amazing release. To get in the news nowadays, you need a mass murder, a scandal or PR hype. The sole publicity for the release of the Codex Vaticanus was one modest tweet. Yes, a twiddling, tiny tweet. I suppose that all of the digital project's funds must go into actually scanning the books and getting the files into the servers.

I will keep a continuing watch on what they are digitizing in such honorable secrecy and present an occasional summary on this blog or on my Twitter feed. [This is Piggin's Unofficial List 1.] If you know of anyone else tracking the BAV digitization project, I would be happy to contact them. Follow this blog, or follow me on Twitter @JBPiggin and I will keep you up to date.

This post originally ended with some debate on the "oldest bound book" hypothesis, but since that material grew so long, I have moved it to a separate blog post.

Geh mir is fad, schaumer in u:scholar

10 hours ago