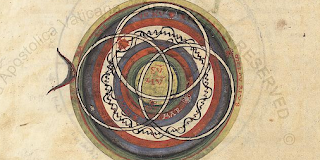

Only two manuscripts of this work exist. The other, from Fulda, is at the New York Academy of Medicine and was rebound nine years ago. The Vatican's manuscript, Urb. lat. 1146, has been reproduced by an Italian publisher as a facsimile costing 1,560 euros, but since June 1, it has been possible to read it for free at Digita Vaticana. Here is one of the illuminations, showing a couple of birds destined for the pot:

Unlike a modern cookbook, De re coquinaria skimps on essential information about ingredient quantities and cooking times. It lacks the glossy photographs of calamari balls in beds of salad which we would now consider obligatory in a cookbook. It is easiest to enjoy it in the 1926 translation to English by Joseph Dommers Vehling, which has been lovingly digitized for your tablet computer at Project Gutenberg. Vehling's edition is enriched with line drawings adapted from other Roman sources.

Apicius is refreshingly blunt in his views on food purity: taste was what mattered, not the 21st-century obsession with avoiding adulteration. Ut mel malum bonum facias (spoiled honey made good) is one of his straightforward counsels: How bad honey may be turned into a saleable article is to mix one part of the spoiled honey with two parts of good honey. Quite. Where's the problem?

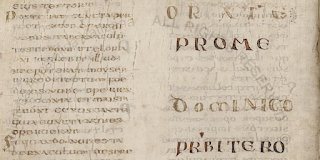

The other major arrival in the June 1 batch of digitizations is the

When the Goths conquered Spain, they initially barred intermarriage between their own people and their Roman subjects and maintained separate legal systems for the two populations. But in time, the legal systems were merged and the Liber is the resulting synthesis, a masterwork of jurisprudence which was drawn up in about 654 under King Recceswinth.

This copy, which once belonged to Queen Christina of Sweden, was penned in the early 8th century [probably: see comment below] in Urgell, Spain and is number 287 in Ainoa Castro's survey & blog of Visigothic-script manuscripts.

Here is the full list of 58 manuscripts added June 1, raising the posted total to 2,077:

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.D.172

- Arch.Cap.S.Pietro.D.178

- Barb.gr.310

- Barb.gr.549, book of hours, 1480

- Barb.lat.393

- Barb.lat.2154.pt.A, Roman antiquities, in the codex that also contains the Chronograph of 354 drawings

- Barb.or.136

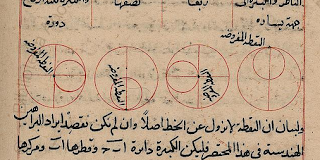

- Barb.or.149, eight-part cosmological map by Adam Schall von Bell, the first European in the court bureaucracy in Beijing, featured in Rome Reborn

- Borgh.237

- Borg.ar.71

- Cappon.9, psalter

- Cappon.12, history of Florence

- Cappon.18

- Cappon.27.pt.2

- Cappon.27.pt.3

- Cappon.28.pt.1, compilation of Italian proverbs including the following: Pena patire per bella parere. Delle femmine quando per apparire belle s'acconciano, e strappano, o, sbarbano i peluzzi, che hanno pel viso, e soffrono dolori in acconciature di testa e simili frascherie. Dicesi anche Per bella parere pena convien' patire. Which translates as, "Suffering pain to look beautiful." This item is now being used as a fundraiser (see below for link)

- Cappon.30

- Cappon.31

- Cappon.33

- Cappon.34, Istoria del Sacco di Roma

- Cappon.42

- Cappon.45

- Cappon.46

- Cappon.47

- Cappon.50, copy (1661) of Del Reggimento e dei Costumi delle Donne by Francesco da Barberino, now featured as a fund-raiser (see below)

- Cappon.71, Diario: Pietro Aldobrandini

- Cappon.74

- Cappon.82

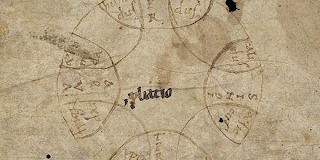

- Cappon.88, Geomantia di Pietro d'Abano

- Cappon.121

- Cappon.122

- Cappon.124

- Cappon.135

- Cappon.136

- Cappon.137

- Cappon.141

- Ott.gr.470

- Ott.lat.2453.pt.1, includes 16th-century book title pages

- Ott.lat.2453.pt.2

- Ott.lat.2867

- Ott.lat.2977

- Pal.gr.232

- Reg.lat.689.pt.1

- Reg.lat.1024, the Liber Judiciorum, an early-8th-century code of Visigothic law (probably) copied in Urgell, Spain (above)

- Urb.lat.585, Diurnale Benedictinum: Psalter Romanum, Beuron number 344

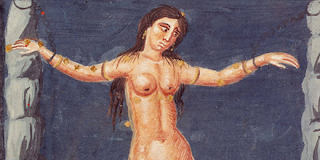

- Urb.lat.899, the wedding events of Costanzo Sforza and Camilla d'Aragona Sforza, 1475: relive a Renaissance wedding! The image below may be of Camilla herself. More details from its Rome Reborn file

- Urb.lat.1146, De re coquinaria ("On the Subject of Cooking"), a 4th-century cookbook (above)

- Vat.ebr.274

- Vat.estr.or.147.pt.13

- Vat.estr.or.147.pt.15

- Vat.estr.or.147.pt.17

- Vat.estr.or.147.pt.19

- Vat.estr.or.147.pt.20

- Vat.lat.49, Renaissance bible

- Vat.lat.55

- Vat.lat.76

- Vat.lat.90

- Vat.lat.93

Digita Vaticana is using Cappon.28.pt.1 and Cappon.50 above for a fundraiser project, so consider donating a few dollars for this worthy cause:

Mss copy (1661) of "Del Reggimento e dei Costumi delle Donne" by Francesco da Barberino. http://t.co/JG38UjExgp pic.twitter.com/DRaodd1Y8S

— Digita Vaticana (@DigitaVaticana) July 8, 2015